Opinion

Urgent Need To Cushion Kenyans From Rogue Digital Lenders

The concept of money lending has been in existence for millennia. Since the commencement of trade, human beings have, on occasion, found themselves on economically unequal situations where one cannot always afford to pay for what they need. It is for this reason that in early civilisations, farmers would borrow seeds and repay with grain after their fields yielded a harvest. They would also borrow livestock on the promise that it would be returned upon the arrival of a new calf.

Over time lending has become more sophisticated which led to the creation of banks which issue loans to borrowers at an interest. The growth of the banking sector necessitated heavy regulation to protect and guide the sectors’ players and to balance risks and opportunities in loan transactions.

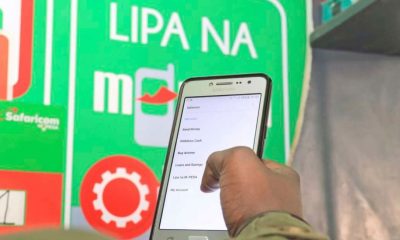

Modern day lending has moved away from the traditional mode where loans were mainly accessible through the banks to digital lending. In Kenya, mobile money services such as M-Pesa and Airtel Money have emerged to offer payment services as well as withdrawal, deposit and transfer of money to consumers through their mobile phones. According to the Communications Authority of Kenya, as of December 2019, mobile subscriptions stood at 53.2 million, with mobile money subscriptions standing at 31.2 million.

Noting the opportunities available in the mobile phone sector, digital lenders have set up shop in Kenya in droves. They offer quick loans, usually processed within twenty-four hours (sometimes instantly) through mobile phone applications. Once approved, the loans are sent to the borrowers’ mobile money accounts.

Digital lenders have seen a boom in their business with the chairman of the Digital Lenders Association of Kenya (DLAK) stating, in 2021, that digital lenders were issuing loans of up to Ksh. 4 billion per month before the Covid-19 pandemic. While they have since seen a reduction of this figure to approximately Ksh 2 billion per month, it remains a significantly profitable industry and this begs the question why the Kenyan Government has dragged its feet in the regulation of the sector. Digital lenders have taken advantage of the lack of regulation in Kenya and proceeded to run their businesses as they deem fit to the detriment of consumers.

One practice that strengthens the calls for strong regulation is the interest and loan fees payable for such transactions. For instance, Tala charges interest rates of between 7% and 17% on any facilities issued to customers for a period of 30 days. OKash on its part charges an interest rate of up to 36% per annum. Branch, another popular digital lender in Kenya, charges interest rates of between 10% and 27% based on the facility amount and the repayment history by the borrower. In comparison, Kenyan banks’ average lending rate as at December 2020 was reported to be approximately 12% per annum.

The above picture demonstrates that, unlike banks which are highly regulated by the Central Bank, digital lenders have the discretion to determine the interest rate charged to a borrower. In the event of default, some of the digital lenders impose late payment fees which are computed based on the outstanding amount and the duration it remains outstanding. Most consumers are not aware of this at the time of taking of the loan. In most cases, the consumer has an urgent need for cash and is oblivious of the amount repayable as interest or facility fees. It is only upon repayment that the financial burden on the consumer becomes apparent and most of them end up defaulting.

Digital lenders are quick to remedy defaults to ensure they recover their funds. One of the ways they have adopted is by reporting the borrowers to Credit Reference Bureaus (CRBs) which in effect damages the credit reputation of the borrower. Digital lenders have been known to use CRBs to torment borrowers by listing them thus barring them from accessing credit with any other providers, including commercial banks. According to reports in 2020, CRB listing rose from 2.7 million in 2019 to 3.2 million in 2020 which was attributed to digital lenders. Even when the listing is erroneous or where the borrower makes a full repayment, most digital lenders have poor customer care support teams, and the delisting takes a significant amount of time to be effected. This in turn leads to decreased access to credit on the part of the consumer.

Data protection has also come to the fore in the digital lending industry. Currently, if a consumer wishes to access a digital loan, they must accept the terms and conditions of use of the application. Some of these terms are unfamiliar to the ordinary consumer and most usually click “Accept” to access the services. In addition, the applications require the user to give certain consents on their mobile phone, including access to text messages and contacts. Initially, this seems harmless. However, in the event of default, consumers have come to realise the hard way that one must give to Caesar what belongs to Caesar. Some digital lenders are known to bombard their clients with messages demanding payment and threatening severe consequences for non-compliance. Some lenders are also known to reach out to third parties who, despite not being listed as guarantors, are requested to intervene and request the borrower to repay their facility. This is not only embarrassing to the borrower but also an invasion of the borrower’s right to privacy.

In addition, through their access to contact details on a borrower’s phone, digital lenders are also known to target the borrower’s contacts and send them targeted marketing messages. Some of these messages contain clickbait content suggesting that a loan has been approved. This is notwithstanding the fact that the individual has neither an account nor applied for any loan from the provider. This constitutes not only an unethical behaviour but also a violation of data protection laws.

There have been attempts to regulate the digital lending industry in the recent past. In 2016, the Competition Authority of Kenya directed financial services providers, including digital lenders, to provide details of all charges on their platforms to ensure that the consumer is aware of the charges. In 2018, Treasury published the Financial Markets Conduct Bill which would have regulated digital lenders. Unfortunately, the Bill has never been passed into law due to various contentions on its proposals. In 2020, the Central Bank of Kenya (Amendment) Bill was tabled in Parliament. The object of the Bill is to amend the CBK Act to ensure that CBK regulates the conduct of providers of digital financial products and services. The Bill is yet to be debated and passed by Parliament.

At present the digital lending market remains unregulated and the persons who are adversely affected are the low-income groups who are easily taken advantage of by the digital lenders. There is need to rein in digital lenders under one regulator who can oversee the sector, license players and bring order to what is currently a chaotic industry where the law of the jungle reigns supreme.

In the latest positive development, the Data Protection Commissioner Immaculate Kassait has revealed the investigations following complaints over digital lenders who have breached the confidentiality of personal information.

The firms are accused of resorting to “debt shaming” tactics to recover loans.

This includes use of debt collection agents pursuing borrowers either by informing their friends and family using contact information scraped from their phones or by threatening to tell their employers.

The Data Protection Act bars sharing of data with third parties without consent and gives individuals the right to be told when their data is being shared and for what purposes.

“The Office received complaints from data subjects regarding digital money lending applications. Towards this end, my office has commenced investigations on a total of 67 such complaints in line with the office mandate,” Ms Kassait said without divulging additional information.

Scores of unregulated microlenders have invested in Kenya’s credit market in response to the growth in demand for quick loans, where borrowers can get loans in minutes via their mobile phones.

Borrowers share personal information, including their professions and monthly earnings, when registering with digital lenders.

But besides the pursuit of unpaid loans, digital lenders share personal information with data analysing firms and for marketing.

The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) has previously raised concerns about the abuse of the personal data of borrowers and called on lawmakers to fast-track legislation to provide for the regulation of digital lenders.

Lobbies that had petitioned Parliament during the review of the Bill also said that loan applications are private affairs that should be treated as confidential information.

Digital lenders have saddled borrowers with high-interest rates, which rise up to 520 percent when annualised, leading to mounting defaults and an ever-ballooning number of defaulters.

The Data Protection Act further compels firms to disclose to individuals and customers the reasons for collecting their data and ensure that the confidential information is safe from infringement by unauthorised parties.

Offences under the Data Protection Act attract a fine of up to Sh5 million and or imprisonment for a term not exceeding to 10 years or both.

“Infringement of provisions of the Kenya Data Protection Act (DPA) will attract a penalty of not more than Sh5 million or, in the case of an undertaking, not more than 1 percent of its annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is lower,” the Act says.

“Individuals will be liable to a fine not exceeding three million shillings or to an imprisonment term not exceeding ten years, or to both.”

Scores of unregulated microlenders have invested in Kenya’s credit market in response to the growth in demand for quick loans, where borrowers can get loans in minutes via their mobile phones.

The firms are accused of resorting to “debt shaming” tactics to recover loans.

This includes use of debt collection agents pursuing borrowers either by informing their friends and family using contact information scraped from their phones or by threatening to tell their employers.

The Data Protection Act bars sharing of data with third parties without consent and gives individuals the right to be told when their data is being shared and for what purposes.

“The Office received complaints from data subjects regarding digital money lending applications. Towards this end, my office has commenced investigations on a total of 67 such complaints in line with the office mandate,” Ms Kassait said without divulging additional information.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoEx-Inchcape Kenya CEO Sanjiv Shah Charged With Bank Fraud

-

Development1 week ago

Development1 week agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWaweru’s Bank Pockets Sh1.16 Billion from KPC IPO While Ordinary Kenyans Fled the Sale

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNIS Kismu Hotel Secret Tape That Sealed Gachagua’s Fate and MP Ng’eno Death in A Chopper Crash

-

Investigations2 days ago

Investigations2 days agoSOLD TO THE BULLET: How the Bodyguard Handed MP Ong’ondo Were to His Killers

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoInvestor Sued Over Sh30,000 Fee to Access Runda Road

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoI Swore Never To Hire The Chopper Again, Author Recalls Harrowing Experience in Helicopter That Killed MP Ng’eno Alleges Poor Maintenance By Owners

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoDid Festus Omwamba Take the Fall? The Puzzle of a Senator’s Ouster and a Call to the CS