Investigations

Part II: Relationship Between Dandora Dumpsite Cartels And The Political System

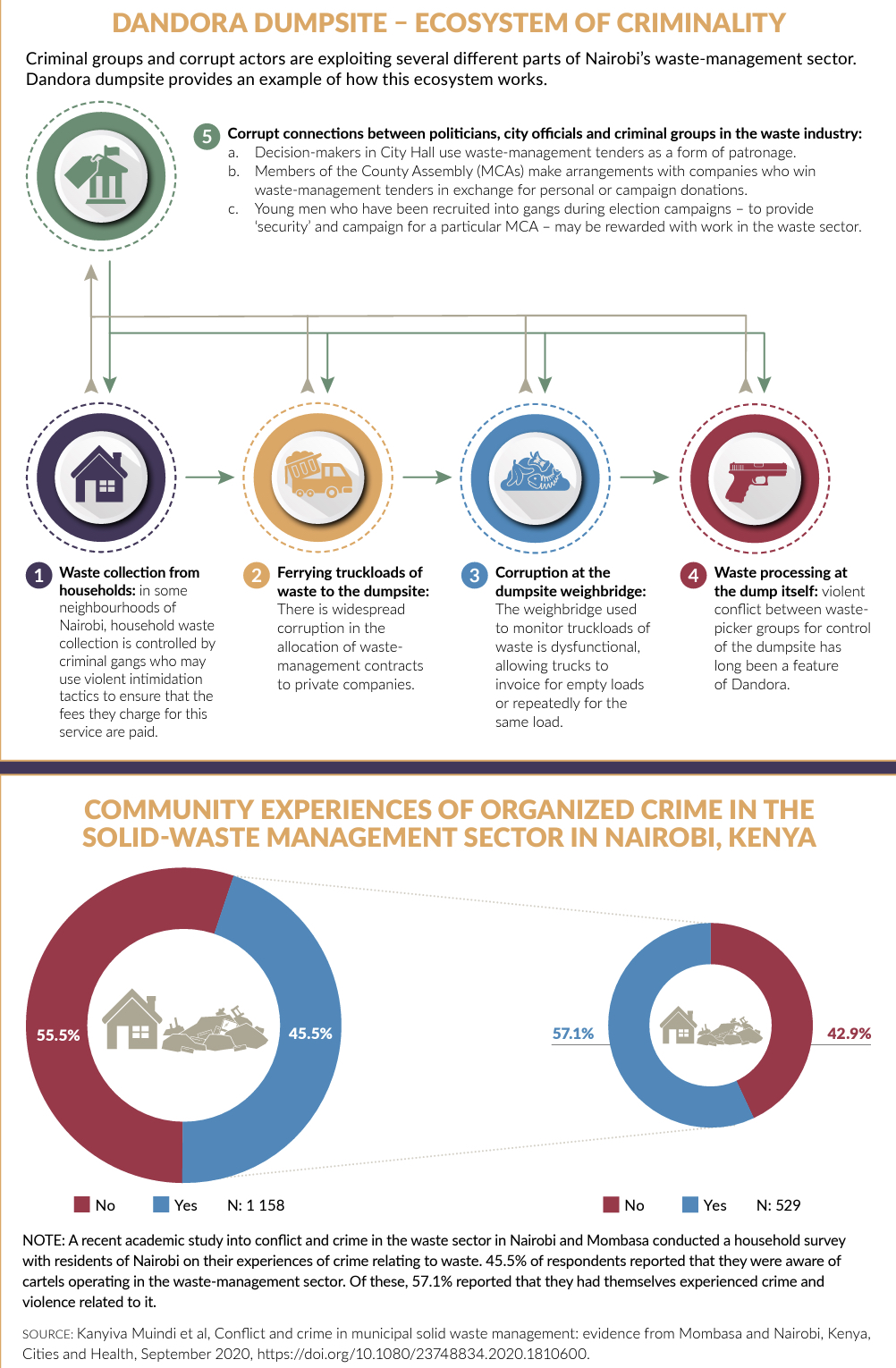

There is an intricate web of relationships stretching between City Hall and Dandora dumpsite, connecting politicians, private waste companies and gangs. In interviews in January 2020, the GI-TOC was told that the waste-management tender process was used to influence members of the county assembly to ensure their support for leading political figures.

Some assembly members make arrangements with the companies who win tenders in exchange for personal or campaign donations, and request that these companies hire certain young people to act as rubbish collectors. These young people are typically the same men who have worked for the assembly members as ‘security’ during their election campaigns.

They largely just move waste from households to a central collection point, where it is collected by trucks belonging to either the county or private companies to go to the dumpsite. ‘Some of the criminal groups here were started by some particular members of the county assembly who had during election campaigns promised the because they demand fees from residents for the job that is really undertaken by the county government,’ says an official of a residents’ association in Buru Buru Estate, Nairobi.

This picture of corruption is consistent with the findings of a recent study on the waste management sector in Nairobi and Mombasa, which reported that ‘recurrent in the discussions [with respondents was the idea that] corruption within the Nairobi County Council was to blame’.

‘Procurement in [the waste-management sector] is fraught with so many irregularities. And this has been going on decades on end, and keeps defying every change in the leadership at City Hall,’ says a veteran news reporter embedded at City Hall. A senior official in the Revenue Department of the Nairobi County Government highlighted the risks of challenging the status quo, saying ‘you don’t ask questions about the management and operations at the dumpsite unless you want to be eliminated’.

The corrupt way in which waste is managed in Nairobi has sapped the county of resources to provide wasteremoval services and left neighbourhoods to be extorted by criminal service providers. According to the senior official in the Revenue Department, City Hall used to collect ‘millions of shillings in revenue in a month from the dumpsite about five years ago but now all it gets is KSh50 000 [US$460] per week’. The fraud and lack of oversight that accompanies the criminalization of the waste-management sector is so severe that Nairobi does not even know how much rubbish it actually produces, and so how much needs to be collected.

Some reports indicate Nairobi produces 2 500 tonnes of rubbish per day, while others show 3 500 tonnes. The level of procurement irregularity such as double invoicing, and the proliferation of illegal an unofficial dumpsites as transporters avoid Dandora due to its poor access, the dysfunctional weighbridge and the fines levied by gangs makes exact estimates nearly impossible.

An International Phenomenon Borne Out Of Local Political Factors

The complex ecosystem of criminality and corruption seen at the Dandora dumpsite is a reflection of the systemic vulnerabilities seen in the waste sector elsewhere in the world, but it has also been driven by local factors.

Nairobi, like other cities in Kenya, has seen rapid urban growth over the past 30 years. Over that time, waste production has grown massively, while political developments paved the way for violent actors to enter the waste sector. The austerity measures of the 1990s which resulted in the City Council (now the City County) retreating from service provision led to the informalization of the economy of Nairobi and the entry of private actors into urban service provision and increased competition for clients and control competition that in some instances became violent.

This became an entrenched problem in the first decade of the new millennium as political actors offered impunity for illicit enterprises to criminal gangs who worked for them during campaign periods. The failure to deal with more ‘white collar’ forms of corruption in the city administration also allowed corrupt political actors to operate with impunity. Gangs and other groups have, in some cases, become wealthy through providing informal services or taxing residents for transport, waste removal and electricity and water provision services that the state has failed to provide.

Neither is this trend likely to change in the near future: Nairobi is continuing to urbanize, but this expansion now comes at a time when waste management an economy that is critical to the environmental and population health of the city has become deeply criminalized.

(GI-TOC)

The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime is a global network with 500 Network Experts around the world. The Global Initiative provides a platform to promote greater debate and innovative approaches as the building blocks to an inclusive global strategy against organized crime.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 days ago

Grapevine2 days agoAlleged Male Lover Claims His Life Is in Danger, Leaks Screenshots and Private Videos Linking SportPesa CEO Ronald Karauri

-

Lifestyle5 days ago

Lifestyle5 days agoThe General’s Fall: From Barracks To Bankruptcy As Illness Ravages Karangi’s Memory And Empire

-

Americas2 weeks ago

Americas2 weeks agoEpstein Files: Bill Clinton and George Bush Accused Of Raping A Boy In A Yacht Of ‘Ritualistic Sacrifice’

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoCooking Fuel Firm Koko Collapses After Govt Blocks Sh23bn Carbon Deal

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoABSA BANK IN CRISIS: How Internal Rot and Client Betrayals Have Exposed Kenya’s Banking Giant

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoEpstein Files: Sultan bin Sulayem Bragged on His Closeness to President Uhuru Then His Firm DP World Controversially Won Port Construction in Kenya, Tanzania

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAUDIT EXPOSES INEQUALITY IN STAREHE SCHOOLS: PARENTS BLED DRY AS FEES HIT Sh300,000 AGAINST Sh67,244 CAP

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoPuzzle Of Mysterious 15 Deaths of Street Children in Nairobi Under A Month and Mass Burials