Coronavirus

Will COVID-19 Be the End of Africans in Guangzhou? I Think So, and This Is Why

Migration to China will never be the same after COVID-19. The health crisis and its consequences will severely impact on local, translocal, and transnational forms of migration. Once COVID-19 ceases to be a threat, foreigners in China will face a new regime of mobility characterized by artificial intelligence-based surveillance technologies.

In a post-pandemic China, there will be little or no room for the irregular forms of migration, mobility, and abode that have made possible the existence of thriving African communities in the Pearl River Delta region.

Is this the end of African migration to China as we know it?

Will COVID-19 fundamentally change the ways in which we think about migration and mobility in the PRC, and in the world at large?

I think so.

As it is now well known, over the last fortnight, an ongoing number of incidents have emerged through social media where black people have been mistreated, persecuted, evicted from their houses and hotel rooms (without prior notice which has effectively left many of them homeless and denied entrance into commercial venues (such as restaurants) in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong province.

These incidents were triggered by Guangzhou’s local government decision to implement a strict surveillance and testing program and impose a 14-day quarantine on all African nationals, regardless of travel history or testing results.

These measures were supposed to prevent a potential outbreak in this foreign community. However, they got out of control.

The deluge of evidence shared through social media prompted a strong, and unprecedented response in Africa, where many governments summoned Chinese ambassadors to answer for the incidents.

A great deal of the indignation on the African side was compounded by the fact that many in the continent saw Africa’s role in the early days of the pandemic as strongly supportive of China.

So, the images of black people sleeping under bridges, families with children being evicted from their legally rented places of abode, as well as entrance and service denial to blacks, were seen by many not only as a form of Chinese racism but, perhaps more importantly, as a Chinese betrayal of African solidarity in these difficult times.

Africa’s strong diplomatic response forced China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to address the issue.

Unsurprisingly, China’s response was to deflect and spin the narrative as yet another situation distorted by Western media and fake news, and to point out that China does not discriminate against any foreigners.

A crucial element in the attempt to spin the narrative has been to emphasize a couple of COVID-19 related incidents: the first around a Nigerian patient who after testing positive for the virus attempted to escape confinement and violently attacked medical personnel.

The second incident relates to a group of Nigerians who, while infected, were roaming around the city and patronizing restaurants and shopping centers.

These cases have effectively been used to shift the blame onto the African population for not abiding by the rules.

COVID-19 may well mark the entrance to a new stage in the process of the construction of a global architecture of control and surveillance. African overstayers and the thriving commercial sectors in which they insert themselves may be among the first ‘victims’ of the new normal in China.

For the last two decades, Guangzhou has been at the forefront of the African presence in China. Due to the overwhelming presence of foreigners, the city’s foreign population management capabilities have been put to a test. This has often resulted in tensions between foreign communities (mostly West African who often report harassment and discrimination) and local police; and between local, provincial, and national policymakers (while Beijing grants thousands of entry permits to African nationals for diverse political reasons, Guangdong’s authorities feel that they are the ones who have to deal with the urban impacts of Beijing’s policies in relation to African nationals).

The practical implication of this governance disjuncture is that, throughout the last decade, the city of Guangzhou has seen a sharp rise in the numbers of foreigners that overstay their visas.

In 2014, in the context of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, and to allay fears of a potential spread in China, Guangzhou’s government reported that some 16,000 Africans were legally residing in the city. Last week, in the midst of the controversy, local authorities reported that the whole African population, consisting of some 4,500 individuals, had been tested. A sharp decline in the population in only six years. However, these figures describe the legal residents, not the overstayers. It is well known that visa overstayers (mostly West Africans) account for a significant portion of the African population in the city.

A great deal of the intense commercial activity that takes place between Guangzhou and places like Addis Ababa, Mombasa or Lagos is organized by them. As in many other parts of the world, one of the paths that these overstayers take is that of hiding (or ‘losing’) their passports. By doing so, they ‘voluntarily’ become undocumented, and effectively set themselves down a highly precarious path where the main aim is to be untraceable if caught overstaying.

Untraceability, however, does not bode well in a pandemics scenario where asymptomatic individuals shed the virus, and where one of the main strategies is to ‘test and trace’ in order to mitigate.

Accordingly, Guangzhou’s longstanding overstayer population is cast in a new light under COVID-19. Local authorities not only fear an outbreak among the city’s foreign communities (especially amongst a group of foreigners without clear, stable and documented identities) but also a central government crackdown/purge on them (the local authorities) were Guangzhou’s foreign community to become a virus hotbed. The impossibility of fully managing and/or controlling the overstayer population exacerbates these pandemic-related fears and anxieties.

[Technology, surveillance and foreign mobility in post-pandemic China] COVID-19 is proving to be a landmark in terms of the relation between technology, mass surveillance and mobility control in the country. From the use of robots and drones to facial recognition and multiple apps, one of the most widely reported aspects of the Chinese response to the outbreak has been the country’s reliance on technology and artificial intelligence.

At this point, it is impossible to ascertain for just how long we will live with COVID-19. It is not unthinkable that special mobility measures could remain in place even after COVID-19 ceases to be a threat. In a post-pandemics China, undocumented individuals will have a hard time trying to circumvent these new technological hurdles.

For example, without a legal abode, it is impossible for foreigners to apply for Alipay Health Code, a system that assigns a color code to users indicating their health status, and determining their access to public spaces such as malls, subways, and airports. This is having a significant impact on the forms of mobility that are allowed, and the ones that are disallowed, in the country.

In the past, foreign migration in the country was driven by the traditional logics of trade (e.g. commercial migrants) and, for those with illegal status, a cat-mouse circumvention game. In the near future, the new regime of foreign mobility in China will be a post-pandemic one driven by rationales of crisis and emergency.

Fear and anxiety will be the logic of this regime, which will be compounded by surveillance through technology. Indeed, it will be almost impossible to be an undocumented or sans papiers individual in this context. The invisibility and untraceability often associated with undocumented individuals will be regarded by authorities as ‘high-risk’ in the new massive surveillance program in place in China.

COVID-19 may well mark the entrance to a new stage in the process of the construction of a global architecture of control and surveillance. African overstayers and the thriving commercial sectors in which they insert themselves may be among the first ‘victims’ of the new normal in China.

Indeed, this may well be the end of traditional forms of irregular abode, at least in China. COVID-19 may, or may not, be the end of migration as we understood it since the early 20c, but it may well be the last nail in the coffin of an already declining African population in GZ.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Development4 days ago

Development4 days agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoHow Close Ruto Allies Make Billions From Affordable Housing Deals

-

Entertainment2 weeks ago

Entertainment2 weeks agoKRA Comes for Kenyan Prince After He Casually Counted Millions on Camera

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoAmerican Investor Claims He Was Scammed Sh225 Million in 88 Nairobi Real Estate Deal

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

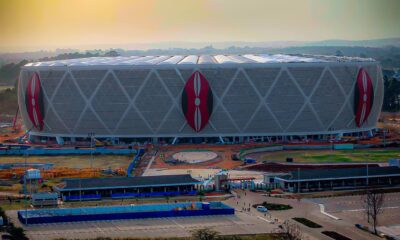

Investigations2 weeks agoTalanta Stadium Construction Cost Inflated By Sh11 Billion, Audit Reveals