Africa

How A One-Time Fugitive Found Fortune In South Sudan

Published

4 years agoon

When Lebanese businessman Ali Khalil Merhi fled Paraguay while awaiting his trial and crossed the border into Brazil in 2000, he escaped mounting scrutiny from authorities. Fresh off a stint in the notorious Tacumbu Penitentiary, Merhi faced piracy charges and suspicions of links to terror financing. At the time of Merhi’s flight from Paraguay, Argentinian prosecutors also wanted to question him about a deadly terrorist attack that had left 86 dead in Buenos Aires in 1994.

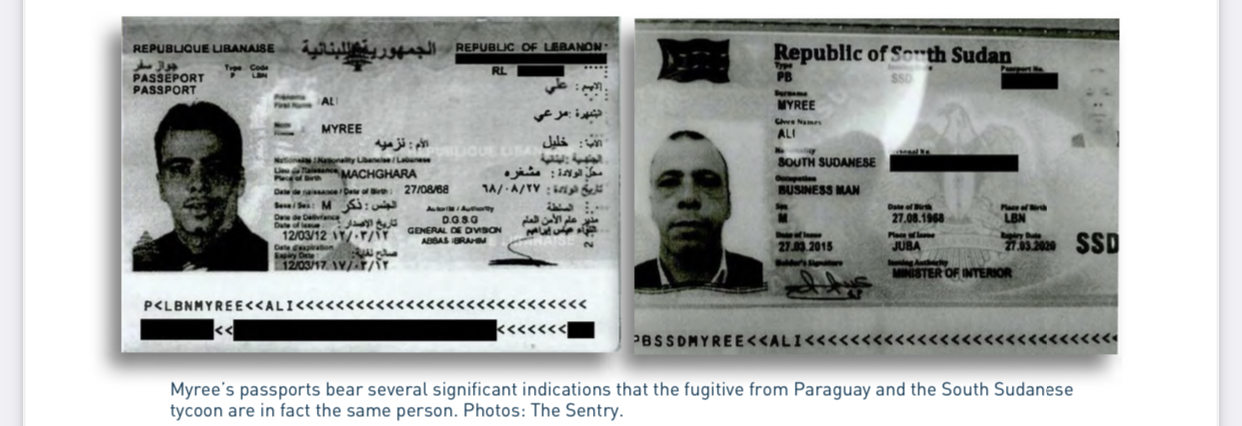

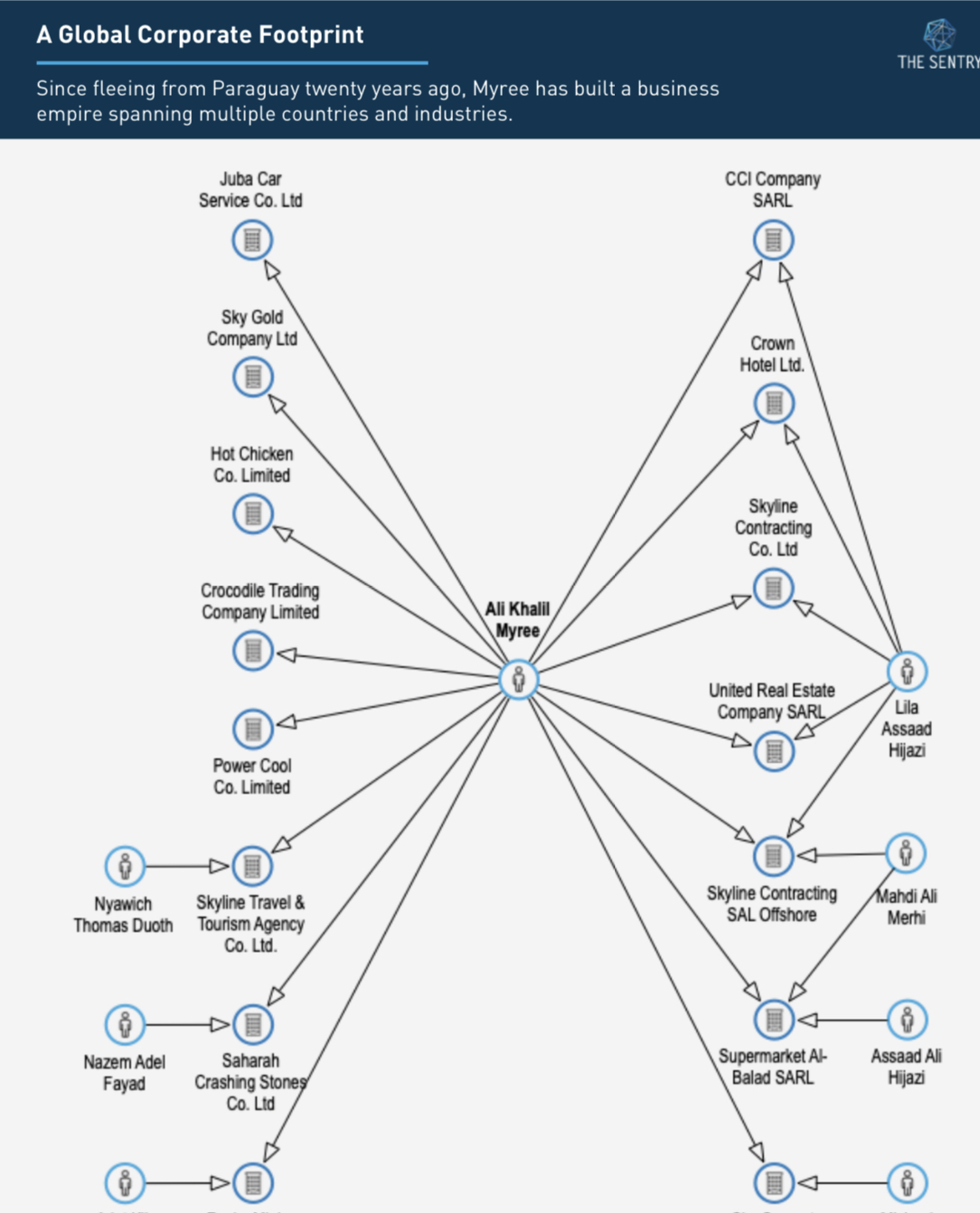

Though the authorities initially investigated Merhi, the trail went cold and the investigation in Paraguay faltered. Meanwhile, Merhi moved on to new terrain. Within 20 years, he had obtained a new passport under the name Ali Khalil Myree, established more than a dozen new companies, and cultivated a new network of powerful government contacts—all in the world’s newest nation.

The Sentry found that for more than a decade, the government of South Sudan has supported the Lebanese tycoon, granting him citizenship, lucrative contracts, and even the title of honorary consul. Since his flight from Paraguay, the newly minted Myree has established himself as one of the most powerful businessmen in South Sudan’s capital of Juba. Along the way, he has registered more than a dozen companies, received public accolades, and partnered with politically exposed persons (PEPs), including the daughter of the president and the daughter of the External Security Bureau chief.

For organized crime groups, smugglers, and suspected terrorist financiers, kleptocracies like South Sudan can provide a safe haven. By cultivating the support of powerful government officials who prioritize their economic interests over the rule of law, businesspeople can conduct their operations with little scrutiny. In South Sudan, meaningful consequences for misconduct have been few and far between for suspected criminals and their government collaborators alike. The result is a prevailing environment of impunity.

The challenge, however, involves more than just a single suspected bad actor. Rather, systemic issues make the nation an attractive refuge for suspected criminals.

Unmasking Ali Khalil Merhi

In July 2020, Ali Khalil Myree received his certificate for consular representation, formally becoming South Sudan’s honorary consul to Lebanon.

Just days after Myree assumed his post, Lebanese newspaper Nida al-Watan published an article decrying the appointment, calling it an “example of diplomatic mismanagement” and claiming that the Lebanese Min- istry of Foreign Affairs had initially rejected Myree’s application due to concerns about his personal history. Shortly after, Juba-based Eye Radio wrote that the Lebanese national was allegedly a fugitive.

According to the article, he had fled Paraguay after being arrested for piracy.

Myree’s attorney, Ali Fayez Rahal, condemned the allegations in the media reports, claiming they had come from “an oppressor who wanted to steal his [Myree’s] livelihoods.”

Rahal, a member of the political bureau of the Amal Movement, a Lebanese political party and paramilitary group allied with Hezbollah, added that Myree provided significant “effort and goodwill…to his African country” and protected the interests of South Sudan’s Lebanese community.10

However, The Sentry can demonstrate—through an extensive body of corporate filings, legal records, pho- tographs, public reports, and social media posts—not only that Ali Khalil Merhi and Ali Khalil Myree are the same person, but also that the new honorary consul continued to engage in questionable business engagements and financial transactions throughout his time in South Sudan.

The Lebanese businessman has established a group of successful businesses in the world’s youngest nation, often alongside family members or PEPs. And while case files in Paraguay are not publicly accessible, a Paraguayan litigator with whom The Sentry spoke explained that under Paraguayan law, a case remains open until the subject of an investigation returns to stand trial—regardless of how many years have passed.

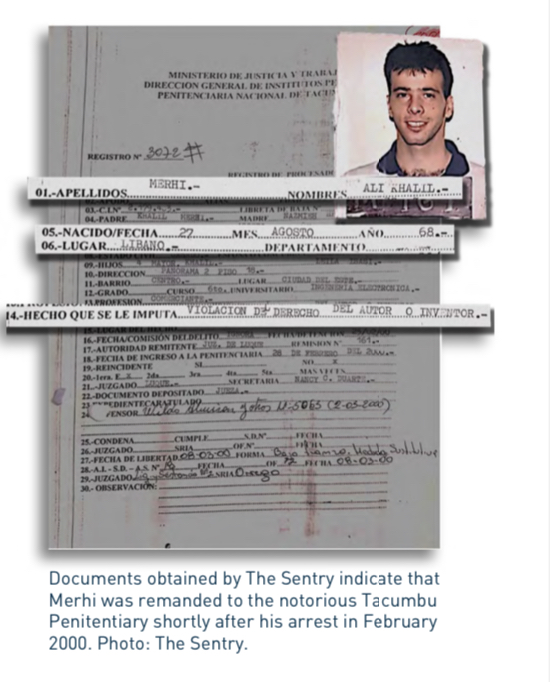

According to processing documents filed with Paraguay’s Tacumbu National Penitentiary, Merhi was born on August 27, 1968—the same birth date recorded on Myree’s Lebanese and South Sudanese passports.

Public reports identify Merhi’s birthplace as Machghara, a Lebanese mountain town, which matches the birthplace listed in Myree’s Lebanese passport on file with South Sudan’s Ministry of Justice.

Additionally, several of Myree’s companies in South Sudan were established alongside other businessmen from Mach- ghara, including one with the Merhi family name.

More significantly, Merhi from Paraguay and Myree in South Sudan are linked through his wife, Lila As- saad Hijazi, whom he reportedly married after his arrest in Paraguay.

On October 25, 2000, Agence France-Presse reported that “during his detention at Tacumbu Prison in Asuncion, Mr. Merhi had married Hijazi, the daughter of a prominent businessman, in accordance with Islamic law. He then invited the 1,700 inmates of the prison to a feast.”

Corporate filings and social media posts reveal that Hijazi has remained in Myree’s orbit in the decades since his departure from Paraguay, appearing alongside him as a shareholder or director of six companies in South Sudan, Lebanon, and Uganda, including Skyline Contracting, an enterprise with major interests in South Sudan.

Myree and Hijazi are also connected on Facebook, and their networks significantly overlap, particularly among members of the Merhi family from Machghara.

They have appeared together in photographs of family reunions and vacations, and on several occasions Hijazi has used terms of en- dearment when commenting on photos of Myree. Shortly after Myree’s confirmation as honorary consul, Hijazi shared a posting seeking an administrative assistant to work at the South Sudanese consulate in Beirut.

The “Megapirate” of Paraguay

When Ali Khalil Myree was tapped for the position of South Sudan’s honorary consul in Beirut in late 2019, it was not the first time his name had been floated for a diplomatic post. More than two decades prior and over 6,000 miles away, a Paraguayan congressman had lobbied for Ali Khalil Merhi to be the country’s consul to Lebanon.

At the time, Merhi was living in Ciudad del Este, a city of 227,000 people located on Paraguay’s border with Brazil and Argentina, a region known as the Tri-Border Area (TBA). Though the country’s decades-long dictatorship under Alfredo Stroessner had ended, corruption remained a major challenge, and this was particularly true in Ciudad del Este, where Merhi had opened his own office. By the 1990s, the TBA had earned a reputation as a harbor for numerous criminal networks.

Merhi seemed to thrive in what the Los Angeles Times called “a global village of outlaws,” alleged- ly cementing himself in one of the region’s chief illicit industries: piracy. Even in a competitive market, Merhi gained a reputation as a “mega-pi- rate,” reportedly becoming one of the most prom- inent distributers of counterfeit entertainment products in the TBA in the late 1990s.

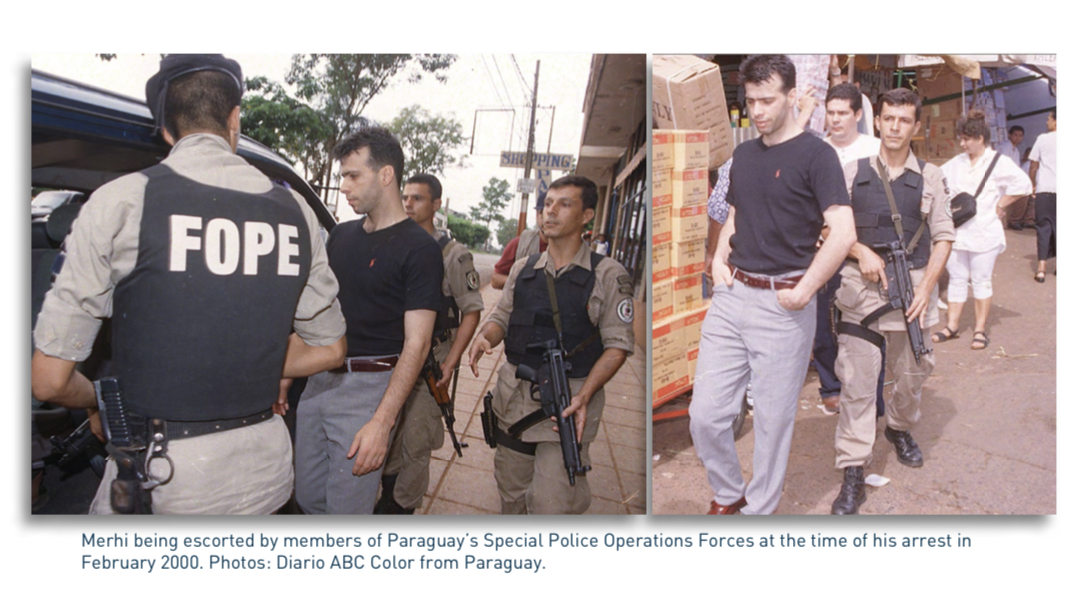

But Merhi’s businesses ground to a halt the morning of February 25, 2000, when Asunción’s Anti-Terrorist Division, in coordination with the Paraguayan National Police’s Special Operation Force, mounted a raid of his home. Report- edly placing explosives to blow in Merhi’s apart- ment door in the Panorama 2 Building, Paraguay- an authorities took both Merhi and his girlfriend into custody on suspicion of copyright violation.

Three days later, Merhi was remanded to Paraguay’s Tacumbu Penitentiary.

When authorities searched Merhi’s offices in the Galeria Page—a shopping complex long considered by the US Treasury Department to be a haven for Hezbollah-linked businesses—they discovered 80 machines ca- pable of producing 20,000 CDs per day, as well as pirated CDs, PlayStation games, Nintendo cassette soft- ware, and logos and packing for several technology companies.

The search also uncovered some- thing more troubling: CDs containing videos of suicide bombers before their deaths; fundraising forms for Al-Shahid, a Hezbollah-backed branch that supports families of deceased operatives; and a bank account number where funds could be sent to Hezbollah’s militant branch, Al-Muqawama (“the Resistance”).

Once Merhi was in custody, his suspected ties to Hezbollah gained attention in Paraguay and neighboring countries. Just after his arrest, his brother Mustafa Khalil Merhi was arrested in Argentina in connection with the 1994 Argentine Jewish Mutual Aid Association (AMIA) bombing.

Shortly thereafter, the Argentinian government filed two requests to interrogate Ali Khalil Merhi in connection with the AMIA bombing.67 The Paraguayan courts fulfilled neither request, however.

The judge hearing Merhi’s case, Ruben Dario Frutos, released Merhi over prosecutors’ objections of flight risk. By June 2000, the accused had reportedly left Paraguay for the Brazilian city of Foz de Iguazu. By October, he had reportedly arrived in Lebanon, where local authorities refused to comply with extra- dition requests. In a public statement, Merhi claimed he had fled for fear of being “assassinated” by police acting on behalf of the US Embassy and Sony, the multinational corporation.

For its part, the press made a point of spotlighting Merhi’s close links with senior government officials, partic- ularly within the conservative ruling Colorado Party, to which he had once contributed significant funds. His relationship with Angel Ramón Barchini, a Colorado Party member of Lebanese descent who had pub- licly defended several people suspected of links to extremist groups in the Middle East, received particular attention. It was Barchini who, in 1997, had recommended that Merhi become Paraguay’s consul general in Beirut; the press also speculated that Barchini may have placed pressure on those investigating Merhi.

He described Merhi as an “honest merchant” and said that he was the victim of persecution after the February 2000 raid. Following Merhi’s flight from Paraguay, sources indicate that he restarted his piracy operations in Lebanon through “a satellite

pirate facility he had opened several years earlier,” according to a report from the RAND Corporation. RAND reported that Merhi’s operation, Skyline Software Systems, was located inthe Ghobeiri neighborhood in Beirut, a Hezbollah stronghold.

Although the Lebanese corporate registry does not contain records for a company by the name of Skyline Software Systems, it does contain records for a company called Skyline CD SARL, which shares a business address and a phone number with

known Merhi enterprise Skyline Contracting SAL Offshore. Sanctuary and Success in South Sudan.

In 2007, as Paraguayan investigators searched for the fugitive Merhi, a Lebanese national named Ali Khalil Myree registered his first company in Southern Sudan, according to the national corporate registry.

Despite the newly minted Myree’s outstanding criminal com- plaint in Paraguay, he acquired the essential capital, bank accounts, and identity papers to begin establishing new com- panies. Shortly after arriving in Southern Sudan, he connect- ed with his neighbor from Beirut, Nazem Adel Fayad.

A Sierra Leone-born Lebanese businessman, Fayad is alleged to have been involved in a counterfeiting scheme with his brother-in- law, diamond and arms trader Aziz Ibrahim Nassour, during the 1990s.

In response to questions from The Sentry, Fayad stated that he had never done any business with Nas- sour. He confirmed, however, that Myree joined Saharah Crash- ing Stones Co. Ltd as a major shareholder in 2007. According to Fayad, their partnership ended after several months due to business disagreements.

In October 2007, Myree incorporated another Southern Suda- nese company, Skyline Contracting Co. Ltd, with his wife, Lila Hijazi. In 2009, Skyline became an approved vendor for the United Nations (UN), supplying $2.23 million worth of cement, electrical wiring and cables, stone, and other construction mate- rials to the UN Procurement Division (UNPD) over the next five years.

As Skyline began its initial projects, Myree’s corporate footprint in South Sudan grew, often alongside as- sociates from Machghara or relatives of senior South Sudanese officials. By 2013, he had registered no fewer than 10 companies in the young country, including Skyline Travel & Tourism Agency, a company jointly owned with Nyawich Thomas Duoth, the daughter of Thomas Duoth Guet, former director general of the General Intelligence Bureau. In response to questions from The Sentry, Nyawich stated that Skyline Travel never became active, as civil war broke out shortly after she acquired shares in the company. Myree also formed Rocky Mining Industries Limited alongside President Salva Kiir’s daughter, Adut Kiir Mayar. In response to inquiries from The Sentry in 2019, Myree said that Rocky Mining never became operational.

Nevertheless, the formation of several businesses in association with PEPs, particularly in the natural resources sector, reflects a broader concern that a select few stand to gain from South Sudan’s kleptocratic status quo.

In July 2012, Skyline Contracting began depositing rounded cash transactions into the personal bank ac- count of General Malek Reuben Riak. Between 2012 and 2014, Skyline paid $88,676 into Riak’s ac- count. In 2017 and 2018, respectively, the US Treasury Department and the UN Security Council placed Riak under sanctions for his role in expanding the conflict in South Sudan, particularly for procuring weapons for the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) and planning the 2015 offensive in Unity State. Follow- ing the UN Security Council’s lead, the EU similarly designated Riak in August 2018.

According to the EU, the Unity State offensive resulted in widespread destruction, including the forced displacement of the local population, the indiscriminate killing and torture of civilians, and the widespread use of sexual violence.

In May 2014, Myree completed construction on his flagship enterprise in South Sudan: the 120-room Crown Hotel, which received South Sudan’s “Hotel of the Year” award.

Although the country had plunged into civil war in December 2013, Salva Kiir personally opened the hotel. Named by the Financial Times as “the capital’s best spot if you want to bump into ‘all the president’s men,’ top bankers, and the city’s dealmak- ers,” the hotel has hosted high-profile government ministers, business executives, and even a Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) president.

The Crown Hotel was registered as Nour Residential Hotel on April 4, 2012. A resolution dated May 6, 2015, identified Myree, Hijazi, and several other members of the Merhi family as the company’s shareholders.

Senior South Sudanese officials have racked up exor- bitant bills while living full time at the Crown Hotel. In 2018, then-petroleum minister Ezekiel Lol Gatkuoth ac- cumulated around $680,000 in hotel fees during a long- term stay, paid for by multinational oil consortium Dar Petroleum Operating Company. Members of South Su- dan’s National Pre-Transitional Committee stayed there in 2019.

Since the Crown Hotel opened, Myree’s companies have received lucrative government contracts and licenses for natural resources. His mining firm, Sky Gold Company Ltd., received a license to explore for gold in Central Equatoria on August 18, 2015. On May 23, 2019, Gen- eral James Hoth Mai unveiled a Skyline Construction project, the Ministry of Defense’s new headquarters, also known as Eagle House.

An imposing, six-story structure, the building has reportedly been outfitted with state-of-the-art surveillance cameras and bulletproof glass. It cost the government of South Sudan more than $40 million.

Meanwhile, numerous members of the Merhi family have been listed as shareholders of Myree’s business- es in South Sudan and Lebanon, and they have visited the luxurious Crown Hotel or made their home in South Sudan.

For example, Mahdi Merhi, who lists his residence as Juba on social media and who has studied tourism and hotel management, has been photographed alongside Myree at numerous business functions and with Myree’s son from Paraguay, Khalil Merhi Sosa Otto. Another son, Mostafa Merhi, attended the Eagle House’s grand opening in 2019.

Since his arrival in South Sudan, Myree has enjoyed an explosive rise to prominence, receiving major contracts

and construction projects from the government and international bodies. This photograph from May 2019 was taken at the inauguration of the new Ministry of Defense headquarters. President Salva Kiir, Ali Khalil Myree, and

Lila Hijazi can all be seen on the dais. Photo: South Sudan Consulate.

Allegations of past misconduct notwithstanding, Myree has continued to appear publicly, including in his capacity as honorary consul. In October 2020, he traveled to an internally displaced persons camp in Man- galla, South Sudan, where he delivered food aid.

In December 2020, when the Honorary Consulate of the Republic of South Sudan opened in Beirut, Myree attended the festivities alongside Mayen Dut Wol, under- secretary of South Sudan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ambassador Victoria Aru, South Sudan’s director of visas and passports.

Disrupting Kleptocracy, Improving Security

The example of Ali Khalil Myree shows why addressing state capture is more than a humanitarian concern— it is an international security imperative. Myree has for decades conducted business in places where the rule of law is weak, thriving where oversight institutions have been gutted by kleptocratic regimes. Neither his past as a fugitive nor his suspected links to potential terrorist financing have prevented him from continuing his international business activities and personal travels.

In South Sudan, he has enjoyed access to bank accounts, travel documents, and multi- million-dollar contracts, all while maintaining close relationships with influential politicians and high-ranking military officials. Operating within the country’s kleptocratic status quo, he has landed major deals without disclosing information vital to the public interest. High levels of corruption and weak systems of governance like those in South Sudan not only enable re- pression and violence but also drastically increase a jurisdiction’s appeal to organized criminal networks, including mafia-type organizations and terrorist groups. Feeble law enforcement organizations and inade- quate customs controls further embolden bad actors engaged in illicit enterprises from terrorism to drug and weapons trafficking.

Governments, law enforcement agencies, and financial institutions have numerous tools at their disposal to insulate South Sudan’s banking sector from future abuse, empower its oversight institutions, and enhance transparency. Most significantly, they can investigate and, if appropriate, impose meaningful consequences on those involved in misconduct. Nothing less than a coordinated effort to promote the rule of law, strengthen democratic institutions, and demand accountability can stem the tide of abuse.

Source: The Sentry.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

📩 Got a Tip, Story, or Inquiry? We’re always listening. Whether you have a news tip, press release, advertising inquiry, or you’re interested in sponsored content, reach out to us! 📬 Email us at: [email protected] Your story could be the next big headline.

You may like

Court Blocks Automatic Absorption of Ex-NHIF Staff into SHA

DCI Summons MP Allied to Gachagua Over Saba Saba Chaos

Embattled DIG Lagat Hires Top Lawyer As He Eyes Return To Office

Inside Raila’s 1,880 Member Intergenerational Conclave To Begin in August

Ahmednasir’s Law Firm Caught Up in the Middle of Zakhem’s Debt Row

My Husband Was a Pastor in Church, But a Demon to Us at Home

‘Ruto ni Tutams We’ll Rig If We Have To’: Fatuma Jehow’s Shocking Admission Sparks Electoral Integrity Firestorm

National Irrigation Authority CEO Charles Muasya On The Spot Over Tender Irregularities

Adani Whistleblower Nelson Amenya Lifts Lid on Scandalous Sale of Kipini Conservancy

KUCCPS Opens Transfer Window for 2025/2026 Students Seeking Programme Changes

From Billionaire to Broke: The Fall of Humphrey Kariuki’s Empire

How NCBA Software Engineer Opened Floodgates For Mobile Banking System Fraud

Investigation Exposes Alleged Sex Crimes at Alliance Girls High School Amid Institutional Cover-Up

EXCLUSIVE: How Corruption and Mismanagement Have Brought Kenyatta National Hospital to Its Knees

Housing PS Charles Hinga Entangled in Sh 2B Tender Scam

WATCH: New CCTV Footage Reveals Police Brought Ojwang to Hospital Already Dead

Inside the Kibaki Estate Dispute: Power, Bloodlines & the Unfolding Legal Drama

Details Emerge In How ‘Death Squad’ Hatched Plan To Keep Dark Ojwang’s Interrogation Secret in Cell Ending in Death

Former PS Warns of Hidden Hand Behind Mwaura’s Sh1.6B HF Group Acquisition, Predicts Delisting

Police Officer Who Shot Mask Hawker During Protests Arrested

Most Popular

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoInvestigation Exposes Alleged Sex Crimes at Alliance Girls High School Amid Institutional Cover-Up

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoCS Alfred Mutua Embroiled in Custody Battle After A ‘Quick’ Moment With Kenyan Girl in Dubai

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoOle Kina Fragrance Sets Kenyan Market Abuzz with Million-Shilling Expansion

-

Opinion2 weeks ago

Opinion2 weeks agoWhy Ruto Dumped Isiolo Governor Abdi Guyo: A Political Betrayal in the Making

-

Americas1 week ago

Americas1 week agoHow A Nigerian Yahoo Boy’s Elaborate Plan to Scam Trump Backfired As FBI Goes After Him

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIrony of Lydia Mathia Seeking Court Interventions Months After Calling Court Orders ‘Mere Papers’ While Spearheading Evictions

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoMoses Kuria Resigns from Kenya Kwanza Government

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoOutrage as Kenya Agrees to Buy Defence Equipment From UK in Ksh12.5 Billion Deal