Opinion

EXPLAINER: Why Judges Break Pens After Death Sentences

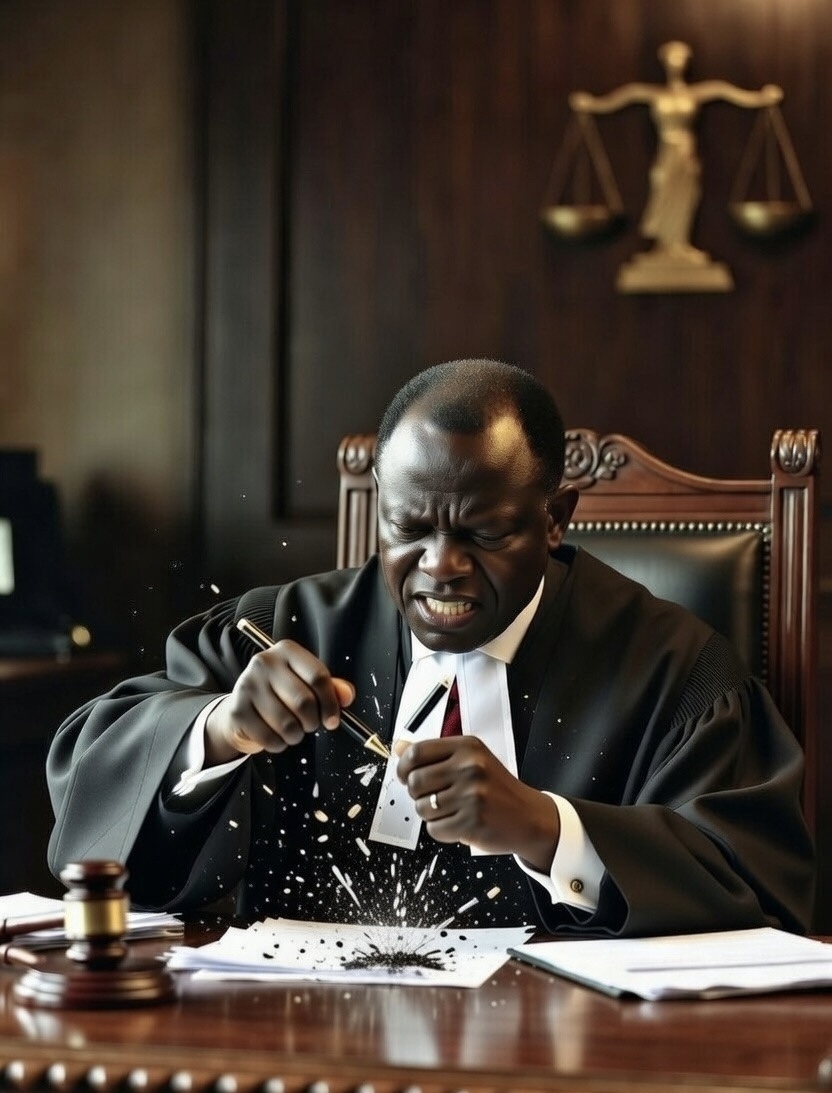

When a Nyeri judge snapped his pen after sentencing a child killer to death last week, social media erupted. The gesture is centuries old, steeped in imperial history, and carries layers of legal and moral symbolism. We trace its origins from the Mughal courts of India to the packed courtrooms of modern Kenya — and ask what it tells us about a country that still sentences people to death but has not executed anyone in nearly four decades.

On the morning of Thursday, 19 February 2026, the Nyeri High Court was packed. Families of the victim, curious members of the public, and journalists crowded the gallery as Justice Kizito Magare prepared to deliver judgment on Nicholas Macharia, a 35-year-old man who had defiled and murdered seven-year-old Tamara Blessing Kabura. The Grade One pupil had gone missing from her mother’s market stall on 24 May 2025. Two days later, CCTV footage from a nearby spare parts shop placed Macharia walking with the child. Officers arrested him and he led detectives to his house, where the little girl’s body lay buried beneath his bed.

The court described the crime as premeditated and executed with utter disregard for human life. Macharia had pleaded guilty after two reversals of his plea, and even his mitigation counsel, Mahugu Mbarire, conceded the gravity of what his client had done, asking only that the court consider rehabilitation as an alternative. The court was unmoved. Justice Magare imposed the death sentence.

Then he broke his pen.

To the gallery, the act was dramatic. On social media within the hour, it was sensational. To legal historians, it was an echo of something far older and far more profound — a gesture that traces its origins across centuries of empire, colonial ambition, and the philosophy of justice.

A Quill Broken in Delhi

The practice of breaking a pen or quill after pronouncing a death sentence is most commonly traced to the Mughal Empire, which dominated the Indian subcontinent from 1526 until its slow unravelling in the eighteenth century. The Mughal court system, anchored in Islamic jurisprudence and Persianate traditions of imperial justice, treated the administration of capital punishment as a profound moral and ceremonial act. When a Mughal Emperor or his designated authority signed a farmān — an imperial decree — ordering an execution, the quill with which that decree was signed would be broken. The symbolism was unambiguous: an instrument that had ordered the extinguishing of a life could not be used again for any ordinary purpose. It had been consecrated, in the most terrible sense, to a singular and irreversible act.

The Mughal courts achieved a degree of judicial independence remarkable for their era. Historical records show that during the reign of Aurangzeb, the courts were sufficiently autonomous to decline even the Emperor’s personal request to execute a convict who had already been sentenced. That independence gave the ceremony of sentencing its weight. The breaking of the quill was not theatre. It was the Emperor’s acknowledgement that he had exercised a power he could not rescind, and that the instrument of that power must be retired accordingly.

When the British East India Company began absorbing Mughal governance structures from the mid-eighteenth century onward — drawing selectively, as scholars have shown, on Mughal protocols for adjudicating disputes — several judicial customs crossed with them. British colonial judges in India adopted the tradition of breaking the pen after capital sentencing, and it persisted long after Indian independence in 1947. It survives in Indian courts to this day, though with diminishing frequency as younger judges either remain unaware of the practice or choose not to observe it.

The Parallel European Tradition

The Mughal origin is the most frequently cited, but it is not the only thread in this tradition’s genealogy. In medieval and early modern Europe, particularly in the courts of the German states, France, and parts of Eastern Europe, a parallel practice existed. Judges presiding over capital cases would snap a quill upon pronouncing sentence, sometimes accompanied by words to the effect that the judgment was final and could not be altered. The symbolism varied by region but consistently converged on the same themes: finality, gravity, and the moral weight of ordering a death.

Some European traditions went further. In certain German jurisdictions, the judge would lay down his staff of office after sentencing, a gesture signifying that his authority in the particular matter had ended — that the court had done its work, and the matter passed now to the executioner and, ultimately, to God. These traditions of marking the boundary between judicial authority and the act of execution carried deep theological as well as legal significance in societies where the taking of life was understood as an act that required divine sanction.

From European courts, the custom spread through colonial legal systems. Britain’s vast empire carried with it the common law and, with it, a clutch of judicial customs that took root in Commonwealth jurisdictions from the Caribbean to East Africa. The colonial penal code introduced to Kenya by the British in 1893 stipulated the mandatory death penalty for murder, treason, and armed robbery. The rituals of capital sentencing arrived quietly alongside those provisions.

What the Breaking Pen Says

The gesture carries at least four distinct layers of meaning, each speaking to a different dimension of what capital punishment represents.

The first is finality. As Indian lawyer Poorvi Sirothia has written, once a judge signs a death sentence, the trial court loses the authority to withdraw or revise that order. The pen is broken to mirror that irreversibility in the physical world. What has been written cannot be unwritten; what has been broken cannot be unbroken. This is not merely poetic. It is a solemn acknowledgement that the court has crossed a threshold from which there is no judicial return.

The second is closure of role. By breaking the pen, the judge declares that the court’s work in the matter is done. The sentence passes from judicial hands to the executive machinery of the state — to prison authorities, to the office of the Attorney General, to the President who may or may not exercise the prerogative of mercy. The pen’s destruction marks that transfer of responsibility.

The third is moral weight. Capital punishment is the most severe order a court can issue. The gesture insists that this sentence is categorically different from any other — that it is not a longer prison term or a heavier fine but a matter of life and death in the most absolute sense. Nairobi-based criminal law practitioners who spoke to this publication confirmed that the act is understood precisely in these terms: as a marker of the extraordinary nature of the sentence just delivered.

The fourth, and perhaps the most haunting, is personal distance. Some interpretations hold that the breaking of the pen is a judge’s silent declaration that they never wish to use that instrument for such a purpose again — a rejection, however symbolic, of the act even while carrying out a legal duty. Lawyer Erastus Orina, who confirmed that the practice has no basis in Kenyan statute or criminal procedure, described it as reflecting the solemn responsibility borne by any judge who imposes capital punishment. The pen that wrote the ultimate sentence, he said, should not be used again for such a purpose.

Kenya’s Peculiar Position

Against this historical backdrop, the gesture acquires an additional layer of meaning in Kenya specifically, because Kenya occupies a singular and increasingly uncomfortable position on the death penalty.

Capital punishment has been part of Kenyan law since 1893 and remains so today. Section 203, read alongside Section 204 of the Penal Code, provides that any person convicted of murder shall be sentenced to death. The Prisons Act specifies that such a person shall be hanged by the neck until dead. Death warrants are issued. The machinery of execution exists on paper. But Kenya has not hanged anyone since July 1987, when Hezekiah Ochuka and Pancras Oteyo Okumu — masterminds of the 1982 coup attempt — were executed for treason. Nearly four decades have passed without a single execution.

In that period, presidents have periodically commuted death sentences en masse. President Mwai Kibaki commuted the sentences of over 4,000 death row inmates in 2009. President Uhuru Kenyatta did the same for 2,747 prisoners in October 2016, citing the inhuman conditions of long-term death row imprisonment and the state’s unwillingness to actually carry out executions.

Then in December 2017 came the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Francis Karioko Muruatetu and Another v Republic, which transformed the legal landscape entirely. A six-judge bench declared the mandatory nature of the death sentence for murder unconstitutional, holding that subjecting convicted persons to a predetermined sentence without any opportunity to present mitigating circumstances violated their right to a fair trial and their dignity. The court was emphatic: it did not outlaw the death penalty itself, which Article 26(3) of the Constitution permits, but it stripped away its mandatory character. Judges were henceforth required to weigh aggravating and mitigating factors before deciding whether death was the appropriate penalty in any given murder case.

The Muruatetu ruling produced significant confusion in the lower courts, which attempted to apply its reasoning to other capital offences including treason and robbery with violence. The Supreme Court was compelled to issue further directions in July 2021, making clear that the ruling was confined to murder under Sections 203 and 204 of the Penal Code and that challenges to mandatory death penalties for other offences had to proceed through the courts separately.

Today, death sentences continue to be handed down in Kenya — as Justice Magare demonstrated last week — but they are reserved for what the Supreme Court characterised as the rarest of rare cases involving intentional and aggravated acts of killing. The crime against seven-year-old Tamara Blessing Kabura plainly met that threshold. Macharia had sexually assaulted the child before killing her, concealed her body beneath his bed, and then tried to deceive investigators. The post-mortem confirmed she died of suffocation following the assault.

The Tradition in Regional Context

The practice of pen-breaking is not unique to Kenya on the African continent, though its observance varies considerably across jurisdictions. In Nigeria, where the death penalty remains in force across multiple states and is actively carried out in some of them, judges have been observed breaking pens after capital sentencing, most notably in cases involving armed robbery, terrorism, and murder. The Nigerian Supreme Court’s Chief Justice has participated in sentencing proceedings where the practice was observed, lending it a degree of institutional visibility.

In Ghana, the tradition was observed until that country’s Parliament voted in July 2023 to abolish the death penalty entirely — a decision that followed a broader African trend toward abolition that has seen Equatorial Guinea, Benin, Sierra Leone, Zambia, Chad, and the Central African Republic remove capital punishment from their statute books in recent years. When Ghana abolished the penalty, the pen-breaking tradition became, in that jurisdiction, a relic.

Tanzania, which shares Kenya’s British colonial legal inheritance and Common Law framework, has its own death penalty jurisprudence. The landmark case of Republic v Mbushuu in 1994 tested the constitutionality of the death penalty under Tanzania’s Bill of Rights and produced a nuanced finding that the method of execution — hanging — was inhuman and degrading, even as the penalty itself was held to be constitutionally permissible. Tanzanian judges have been observed observing the pen-breaking tradition, though infrequently.

In India, the tradition is perhaps most deeply embedded, traceable directly to Mughal precedent through British colonial transmission. Indian High Courts and the Supreme Court have seen judges break pens after pronouncing death sentences in cases involving particularly heinous murders. The practice gained widespread public attention in India in recent years as social media amplified moments that would previously have been confined to courtroom observers.

Symbolism in an Age of Digital Records

There is an undeniable tension in the survival of this ritual into the twenty-first century. Modern courts produce digitised records, typed judgments, electronically stored evidence, and appellate processes that are themselves documented across multiple platforms. A judge who breaks a pen after sentencing will typically then sign several further documents — a certified copy of the judgment, the death warrant, court orders — using another pen entirely. The symbolism is understood by participants to be precisely that: symbolic rather than operational.

Some legal scholars argue that this makes the gesture more, not less, valuable. In a system that has become bureaucratised to the point where even the most extreme sentences can feel like administrative decisions, the physical act of destruction insists on presence. It says: something irreversible happened here, in this room, today. A life has been placed in the hands of the state’s coercive machinery. That deserves more than a signature.

Critics, on the other hand, suggest that such gestures risk introducing an element of theatre that is inappropriate to judicial proceedings. Courts are expected to project objectivity and procedural neutrality. A dramatic act — however historically grounded — can appear to personalise a decision that is meant to be strictly legal. In Kenya, where most judges simply deliver the sentence and sign the necessary orders without any ceremony, Justice Magare’s gesture stood out precisely because it departs from the norm.

The gesture does not, of course, alter the legal reality in any respect. Nicholas Macharia retains the right to appeal his conviction and sentence, and given Kenya’s consistent pattern of commuting death sentences before they reach execution, there is a reasonable probability that his sentence will eventually be reviewed or commuted. The death warrant transmitted to the competent authority within thirty days does not guarantee an execution. In Kenya’s legal history, it almost never has.

The Weight of the Gesture

What remains, then, when the cameras stop rolling and the courtroom clears, is the question of what this tradition actually says about the relationship between law and morality, between the state’s power to kill and the individual conscience of the judge who orders it.

In the Mughal Empire, the Emperor who broke the quill was acknowledging that he had exercised the highest and most terrible prerogative of sovereign power. In the colonial courts of British India, the practice carried with it the colonial state’s ambivalent relationship to the lives of its subjects. In post-independence Kenya, where the death penalty is theoretically available but practically suspended — where the sentence is handed down but never carried out — the pen-breaking takes on yet another resonance: it is a symbol of finality deployed in a system that has itself refused to be final.

Justice Magare’s gesture, in that packed Nyeri courtroom, was an act of acknowledgement. It said: a child is dead, the man who killed her has been condemned, this court has done the most serious thing a court can do, and that must be marked. Whether the sentence is ultimately carried out is a question for other hands. The pen is broken. The court’s work is done.

For Susan Wanjiru, the mother of Tamara Blessing Kabura, who seven-year-old disappeared from her market stall on an ordinary afternoon and never came home, no gesture — however ancient, however symbolic — can restore what was lost. But the solemnity of the court’s response, and the centuries of judicial conscience it invoked, is perhaps the closest thing the law can offer to an acknowledgement of the weight of what happened.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoAlleged Male Lover Claims His Life Is in Danger, Leaks Screenshots and Private Videos Linking SportPesa CEO Ronald Karauri

-

Lifestyle2 weeks ago

Lifestyle2 weeks agoThe General’s Fall: From Barracks To Bankruptcy As Illness Ravages Karangi’s Memory And Empire

-

Grapevine7 days ago

Grapevine7 days agoRussian Man’s Secret Sex Recordings Ignite Fury as Questions Mount Over Consent and Easy Pick-Ups in Nairobi

-

Investigations4 days ago

Investigations4 days agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy

-

Economy3 days ago

Economy3 days agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoEpstein’s Girlfriend Ghislaine Maxwell Frequently Visited Kenya As Files Reveal Local Secret Links With The Underage Sex Trafficking Ring

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoState Agency Exposes Five Top Names Linked To Poor Building Approvals In Nairobi, Recommends Dismissal After City Hall Probe

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya