Investigations

Chinese Fraudster Who Stole Billions In The Name Of Kenyans

When Justice Francis Tuiyott made a ruling on June 30 that removed a Chinese national, Giuo Dong (pictured), as a director and shareholder of Catham Properties Limited, there was agreement that the plaintiff could not attend the court sessions because he was being detained.

But both sides could not agree on who was to blame for Guo’s fate – or even why he had been taken into custody. “A feature of this case,” said Justice Tuiyott, “was the unavailability of Guo Dong at the trial.” “It is common ground that he is under detention in China under the Chinese authorities. There is a blame game as to who is responsible for his fate. He (Guo) alleging that it is at the malicious instance of the Chinese defendants in this matter, and they insisting it is because of crimes he committed.”

The ruling brings to an end a bruising six-year legal battle replete with claims of bribery and subterfuge over a Sh600 million property pitting Guo against his business partner-turned-nemesis, Li Wen Jie.But it is the departure of the heavy-built, smooth-talking Guo, nicknamed ‘The Big Boy’, that begs to be answered. The man’s exit from East Africa, and particularly Kenya, was as mysterious as his entry.

Those who knew Guo remember him as a smooth operator who charmed his way into Kenya’s corridors of power even as he marketed himself back in China as the ‘strongest bridge’ over which billions of yuan would flow into investment opportunities in East Africa, particularly land.But before he made his play in Kenya, Guo had established himself in Uganda in the early 1990s. Of course he might have made trips to Kenya as just another unknown Chinese businessman, and only stepped out of the shadows at around the time that the Jubilee government took over the reins of power in 2013.

It was around this time that Chinese billions flowed into the country, with mega projects such as the Standard Gauge Railway being unveiled. In early 2014, Li and Guo came together to form Catham Properties, with the intention of buying prime land in Kilimani to construct apartments. Guo’s shareholding was 85 per cent while Li’s was 15 per cent.

This land, Li told Guo, would cost Sh600 million. Guo was expected to contribute half of the cash, which he told the court that he did. After the transaction had been completed, Guo, the most influential of the two, invited Charity Ngilu, then the Cabinet Secretary for Lands, for the groundbreaking ceremony of Fountain Gardens development in which 140 apartments were to be built. Our attempts to reach Mrs Ngilu, who is now the Kitui Governor, for comment were not successful despite calling several times and sending text messages.

Guo told the court he soon learnt that the title deed for the land was forged and that the land, rather than costing Sh300 million, actually cost Sh100 million. He accused Li and a law firm of involvement in the fraud and said he reported the matter to the police, who launched an investigation.Guo then claimed that Li instituted a process of edging him out of the company. This, he said, was done by two defendants in the case – Tobias Ongalo, an advocate, and his daughter and lawyer Christine Muga. Other defendants in the case were Multi-Win Trading (East Africa) Limited, which had taken over from Guo as a shareholder, Hai-Chen, Peng Zang and Catham Properties. The defendants would, in turn, launch a counterclaim seeking for his ouster as director and shareholder of Catham Properties.

They insisted that both Guo and Li were brokers who were holding the shares in trust for Chinese investors.

Forged signature

Guo said a deed of transfer that had his signature was forged. The defendants countered that he had signed the document in China. At this point, it is worth noting that Chinese investors had been attracted by the spectacular returns on land in Kenya leading to millions of dollars flowing into real estate.

Two Chinese reporters wrote a story in 2016 titled Four Chinese Elders Dug Gold in Africa in which they told of four elderly Sichuanese businessmen who came to Kenya to work on a State engineering project in 2007. “Having realised that there was a great opportunity for profit, these four businessmen quit their jobs and each put up $385,000 (Sh41.5 million by today’s exchange rate) to buy a piece of land and develop it into residential housing. They each ended up making $1.5 million (Sh1.6 billion) from their investment.” Such narratives spurred other Chinese entrepreneurs to come to Kenya in the hopes of making their fortunes.

Unlike State-owned corporations in Africa, which have access to subsidised credit from the Export-Import Bank of China, firms such as those that dealt with Guo raised capital from family and friends, according to a 2016 article by the World Bank. Unfortunately, the funds that flowed from Beijing to Nairobi through Guo and Li were tainted with controversy. If they were not allegedly stolen in Kenya, they were never invested in Uganda.

Because even as Guo claimed to have paid Sh300 million for the Kilimani property – as well as being listed among investors who planned to build a Sh65-billion project in Athi River – he had a court case in Uganda where he had defaulted on a Sh200-million loan from Barclays Uganda. He had also defaulted on another Sh3.2 million loan from DFCU Bank that he guaranteed for his company, Guo Star Enterprises Uganda Limited in 1997. Five years earlier in December 2000, Guo had stood beside Uganda President Yoweri Museveni in a ceremony to hand over the State-owned Lira Spinning Mill to his company Guo Star Enterprises and Tianjin Haihe International Service and Engineering Corporation.

The two Chinese companies promised to invest $20 million (USh73 billion) in the project and employ 500 people. Two decades later, Lira Spinning Mill is “not working at all”, according to a Ugandan journalist that we spoke to. In 2014, Guo and Li, through another company known as Multi-Win East Africa, were talking big about setting up a Sh65-billion African Dubai in Machakos County.

Then Director of External Communications at State House Munyori Buku told one of the local dailies that he was aware of the proposed project that would “push the government’s plan to turn around the country’s economic prospects and help achieve Vision 2030.” “Such projects are a clear manifestation of the Jubilee administration’s plan to take Vision 2030 to the next level,” Mr Buku said. When contacted, Mr Buku asked for more time to refresh himself on the project, saying his memory about it was vague. He promised to get back to us, but had not done so by the time of going to press. Six years down the line, the African Dubai in Athi River – a China city of Kenya with stores, factories, residential homes and offices – remains a pipe dream.

A source said Guo and Li had established themselves as Chinese brokers, and the project might have been used to siphon funds from unsuspecting investors back home. To maintain a veneer of respectability, Guo embraced social campaigns. He would talk of the need to create cultural linkages between Kenya and China and tear down the mistrust that existed between the two nations. In October 2015, he was at the forefront of the official launch of what was dubbed The Grand Exhibition of the Eight Chinese Modern Times at the Nairobi National Museum. During the event he emphasised the need for Kenya to enhance training on Chinese culture in local institutions to build stronger ties. The event was attended by then Deputy Speaker of the Senate Kembi Gitura.

On this occasion, Guo, who a journal article said grew up in Beijing and started off by selling Ugandan coffee to China, had the title of professor. No one could confirm whether Guo had a PhD, let alone if he had completed college. “They say so much about China and the people of China when they come to Africa, and vice versa when they tour China. We must demystify the myths,” said Guo. The Big Boy had established himself as the go-to man on matters China.

In May 2014, when Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Kenya, reporters, rather than field their questions about Chinese investment to the embassy, rushed to Guo for comments.

Impeccable English

Sources said it was easy to see why people gravitated towards him. Unlike most Chinese nationals, Guo spoke impeccable English and possessed an easy-going manner that endeared him to both the man on the street and senior government officials. In late 2015, there were attempts to have him deported. “It is State House which intervened, but indirectly,” said a lawyer. But in court, the defendants insisted that no such plan had been hatched.

Instead, they accused Guo of making up the story “to paint Li in bad light in the eyes of Chinese billionaires.” But Guo is now behind bars in some unknown detention facility in China, which his lawyers insist was part of the grand scheme to edge him out of the company. The matter is said to have sucked in politicians and high ranking officers at the Department of Immigration and the Directorate of Criminal Investigations. The fight between Guo and Li was fierce.

A woman said to be Li’s mistress died mysteriously at the Dubai International Airport after she was hurriedly forced into a plane by police. The death, said Li’s lawyers, happened while Li, who had his own legal troubles, was fighting for his freedom at the Kibra law court. Both sides traded accusations over the incident. Li would eventually be deported in 2016 by orders from the late Interior Cabinet Secretary Joseph Nkaiserry, who declared him a security threat. Then Interior spokesman Mwenda Njoka confirmed the deportation. “There were many complaints against the man and he was finally deported.”

This article was originally published on The Sunday Standard.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Economy2 weeks ago

Economy2 weeks agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoKPC IPO Set To Flop Ahead Of Deadline, Here’s The Experts’ Take

-

Politics2 weeks ago

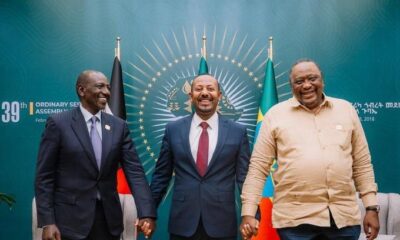

Politics2 weeks agoPresident Ruto and Uhuru Reportedly Gets In A Heated Argument In A Closed-Door Meeting With Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours