Investigations

The Secrecy And Skewed Media Reporting: Uncovering The KDF’s El Adde Attack Cover-up

Today, One year ago, Somalia terror group Al Shabaab laid one of the fatal attacks on Kenya’s troops fighting the insurgency in Somalia. The camp was run down. While the nation was coming into terms and held with grief, the government went on a full defensive and cover-up mission on the attack.

What followed El Adde attack is a now familiar followed a pattern of information twisting and gagging. El Adde added to the long string on the security agencies of ignored warnings, bungled rescues, misinformation, shelved inquiries, and impunity. The State in avoiding accountability has kept off from answering critical questions clouding the attack and ensuring media publications on the attack are sieved to their taste.

Twelve months on, the number of lives lost, survivors and captured soldiers in El Ade attack remain a mystery. The Kenyan Defence Forces have been in Somalia October 2011 on a mission dubbed Operation Linda Nchi aimed at keeping our borders safe and stabilizing the war-torn Somalia. Operating under AMISOM alongside other African nations, the common enemy is the dreaded militia outfit, Al Shabaab.

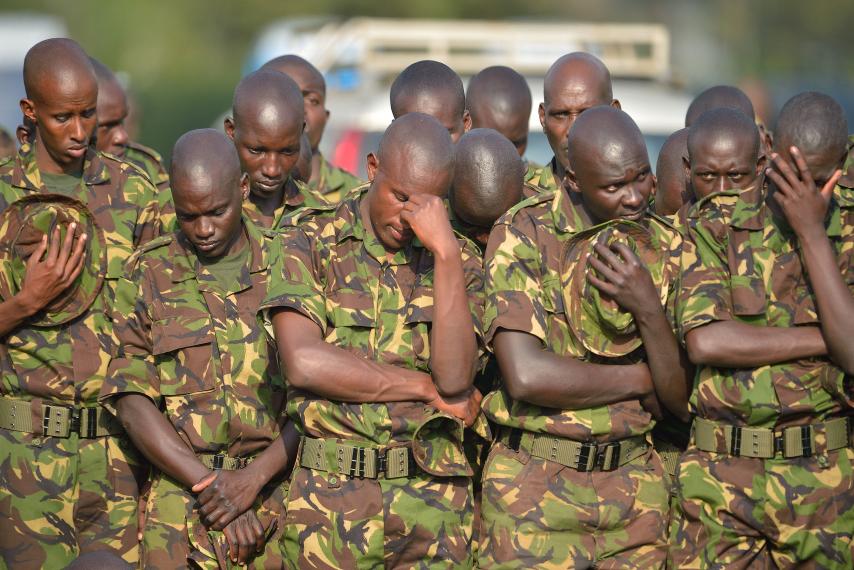

For the period that KDF has been in Somalia, January 15th, 2016 attack on our El Ade camp was the worst and most embarrassing military catastrophe in the recent peace operations. KDF camp was overrun by Al Shabaab militants. Many young lives were lost, our brothers were captured, and military equipment was stolen.

Twelve months on, it’s still not clear how many lives were lost and how many were captured. Investigations have been carried out, but the findings remain secrets, we are not asking too much, but we deserve to know the whereabouts of our brothers. The government chose to make everything a secret opening a gap for speculations on the lives lost ranging between 80 to over 200, primarily an entire company.

In keeping the secret, the government chose to spread the burials so that media would lose interest in covering burial ceremonies and the public also got tired of seeking to know more about that fateful attack. KDF soldiers were instructed not to discuss the El Ade incident. The questions still linger, though, whose fault was it that with heavy military machinery Kenyan soldiers could not defend the camp for hours. Commanders have been blamed, and the fact that the camp was set in an area where the locals were hostile to KDF was another pointer.

Our forces had always maintained a small number of casualties, but this became the biggest embarrassment. Other nations fighting under Amisom have been blamed for not sharing intelligence especially the SNA (Somalia National Army) leading to a heated debate that our troops should be withdrawn and deployed along the borders.

The withdrawal debate has since evaporated in the thin air and recently while celebrating Jamhuri day President Uhuru Kenyatta requested the Western nations (European Union) to help fund the war on terrorism. The American President-elect Donald Trump through his transition team has been reported questioning why America is supporting an ending war on Al Shabaab.

The Kenyan government had not publicized how many soldiers were deployed at the El Adde base when the attack occurred, nor has it confirmed if all those garrisoned there were present when the battle commenced. AMISOM’s register listed 209 troops assigned to El Adde (in a company-plus formation).

But other AMISOM sources suggested there were 160 KDF troops in El Adde on January 15th. A KDF prisoner speaking on al-Shabaab’s propaganda video says 200 KDF troops arrived in El Adde just two weeks earlier.

Officials familiar with the subsequent recovery operations told a recent CNN investigation that “at least 141” Kenyan soldiers were killed.

The El Adde battle might, therefore, represent al-Shabaab’s deadliest attack on Kenyans, even surpassing the earlier massacre at Garissa University on April 2, 2015, where al-Shabaab militants killed 148 people. 7 It included scenes where al-Shabaab paraded and interrogated several wounded KDF

soldiers. The militants also captured approximately thirty military vehicles and a range of weaponry and ammunition. The battle at El Adde is significant for several reasons. For al-Shabaab, the battle provides a significant psychological boost and grist to its propaganda mill. For Kenya, on the other hand, it has the opposite effect. First, the loss of almost an entire company of troops is an extraordinary military event.

Although many important questions remain unanswered, the available evidence points to a long list of operational challenges and problems that reduced the KDF’s ability to repel al-Shabaab’s attack. The underlying problem was the KDF’s poor operational setup and procedures at El Adde, coupled with the decision to deploy such vulnerable forward operating bases in remote areas garrisoned by so few troops in a part of Somalia where al-Shabaab retained considerable freedom of movement.

First, the KDF contingent that was attacked on January 15th had only been in the camp for about three weeks. As General Mwathethe put it, “The troops had just rotated.” This had also been the

case in the al-Shabaab attacks against the AMISOM Bases at Leego and Janaale. Periods of troop rotations are particularly vulnerable because outgoing troops tend to “switch off” and focus on

returning home, while incoming troops may take the time to acclimatize to their new environment. The new soldiers in El Adde had been deployed after Kenya conducted a “relief in place” from December 15 to 21, 2015.

Across-AMISOM relief in place had occurred during November and December 2015. It is not clear if the KDF troops at El Adde were undertaking their first tour of duty in AMISOM or if they were already veterans of the mission. Either way, assuming none of them had previously deployed to El Adde, the newly arrived troops had relatively little time to learn their local environment and detect any warning signs. In this early period, it would have been particularly difficult for troops to discern what types of events and patterns were normal for this area and which

were signs of extraordinary activity.

Another problem stemmed from the poor configuration and design of the El Adde base. At over one kilometer long and nearly a kilometer wide, the El

Adde forward operating base was much too big for a company-plus formation to adequately defend.

This raises questions about the decision to site it there. It would also have been better for a company-sized base to have a triangular rather than a roughly circular perimeter. This would have reduced the number of fronts from which an enemy could attack.

It is also not clear if the KDF soldiers operated external sentry points or regular patrols around the base, particularly at night. If sentry positions were not manned, the concentric circles of perimeter vegetation (thorn bushes) would probably have done little more than obscure the sight and firing lines of the defenders, allowing al-Shabaab attackers to advance to a close distance without receiving much defensive fire. This appears to Procedures in al-Shabaab’s propaganda video.

. #Kenya said it killed these #AlShabaab leaders in airstrikes few years ago. I met them on my last trip to #Somalia. pic.twitter.com/3G4iTXYhpL

— Hamza Mohamed (@Hamza_Africa) January 12, 2017

Another important issue concerns the size of the attacking al-Shabaab force: were KDF troops overrun because they were heavily outnumbered, or was al-Shabaab able to defeat the base with a

Relatively small attacking force? Several factors are relevant here. As noted above, presumably the larger the al-Shabaab force, the longer it would

have taken to muster, leaving some opportunity to detect and warn about an impending attack. Given the attack was launched just before dawn, al-Shabaab must have mustered its force during the

night.

Moreover, it is unclear whether the KDF

defenders adopted the recommended tactics and procedures of standing-to before dawn and dusk. If the El Adde base was considered permanently

under threat of attack, it would likely have been wise to man the garrison’s heavy weapons and armored vehicles 24/7. It is unclear whether this

was being done. Although al-Shabaab’s video has indeed been edited, the level of audible gunfire heard just before the first vehicle-borne IED explosion raises the question of whether the KDF

the contingent was indeed standing-to just before dawn.

On the other hand, al-Shabaab’s video and photos of the deceased Kenyan soldiers show that most of them were wearing full uniform and had access to their weapons. This was not the case, for

example, during the earlier al-Shabaab attacks on Leego and Janaale. Given these extensive defensive challenges, the attacking al-Shabaab force probably

did not need to have the 3:1 attack-to-defense force ratio recommended by most contemporary military doctrines.

Some Kenyans have argued that revealing the identities of the fallen soldiers would hand Al Shabaab a propaganda victory. But Kenya’s

deliberate policy of keeping such information secret has arguably contributed to undermining its credibility to the extent that many Kenyans and Somalis perceive its strategic communications to be unreliable.

While section of Kenyans have argued that revealing the identities of the dead soldiers would hinder the KDF’s battlefield effectiveness. But it is long established practice to name the fallen soldiers in many of the world’s most effective militaries, including the US and UK. If anything, publicly honoring fallen peacekeepers is likely to enhance

their performance because they would know that if they die, they would be publicly recognized, and their families could claim the financial compensation to which they are entitled.

Moreover, the public silence over the status of the KDF hostages is unlikely to inspire confidence among their comrades that they would be taken care of should they are captured. It is, therefore, notable that the KDF recently announced the creation of a special

elite unit to rescue soldiers stranded in battle or lost in enemy territory.

No modern peace operation can succeed if it does not have the support of the local population, and greater clarity on the issue could help reestablish AMISOM’s credibility and demonstrate the sacrifice AMISOM’s troop-contributing countries have made in the effort to bring peace to Somalia.

Similarly, secrecy hands al-Shabaab a propaganda a victory by allowing its narratives (and videos) to gouncontested and shape the dominant narrative of

the event.

Will the war the war continue or will we withdraw, that is up to military operatives decide but in marking the first anniversary of our fallen soldiers at least it is wise to uncover the truth, hide no more secret.

Additional report adopted from International Peace Institute, El Adde Report.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Economy2 weeks ago

Economy2 weeks agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoKPC IPO Set To Flop Ahead Of Deadline, Here’s The Experts’ Take

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoPresident Ruto and Uhuru Reportedly Gets In A Heated Argument In A Closed-Door Meeting With Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours