Business

Safaricom Under Storm As Acquitted Student Vows Massive Lawsuit After Teleco Admits Handing DCI His Private Data Without Court Order

The company’s compliance with an unlawful police request, without demanding judicial authorisation, may constitute a violation of the Data Protection Act.

The acquittal of Moi University student David Mokaya by the Milimani Law Courts has opened a legal Pandora’s box that threatens to embarrass both Kenya’s dominant telecommunications company and the Directorate of Criminal Investigations in equal measure, as the young man’s lawyers announced plans to pursue the State for malicious prosecution while the court itself placed Safaricom on notice over what it described as a blatant and illegal breach of a subscriber’s constitutional rights.

Magistrate Caroyne Mugo, in a ruling delivered on February 19, 2026, did not merely acquit Mokaya of charges that he published false information about President William Ruto.

She went further, pointedly flagging Safaricom as a company with serious questions to answer after it emerged during trial that the telecommunications giant had surrendered Mokaya’s private subscriber data to police investigators without any court order authorising the disclosure.

The magistrate’s remarks were not obiter.

They were deliberate, targeted and carry the weight of judicial censure that Safaricom’s legal and regulatory affairs teams will find impossible to ignore.

The facts of the case, as they emerged during weeks of testimony, paint a disturbing picture of a security apparatus that moved with remarkable speed and remarkable disregard for constitutional safeguards once a social media post touching on the President’s name entered the system.

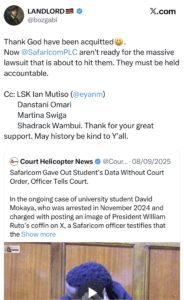

On November 13, 2024, a post appeared on platform X under the username “Landlord @bozgabi” depicting a funeral procession with a military escort carrying a casket draped in the Kenyan flag, accompanied by a caption that investigators said referenced President Ruto.

Within twenty-four hours, a senior police officer identified in court as Michael K. Sang had written directly to Safaricom demanding the subscriber details behind the account.

By November 15, a team of detectives from the Serious Crimes Unit had descended on Eldoret, tracked Mokaya to an area opposite Moi University’s Annex, and arrested him.

A Samsung phone, a laptop and his identity card were seized before anyone had troubled themselves to obtain a search warrant.

It was Chief Inspector Bosco Kisau who delivered the most damaging admissions from the prosecution’s own witness stand.

Under cross-examination by defence lawyers Danstan Omari, Ian Mutiso and Shadrack Wambui, Kisau conceded that he had not been served with a court order authorising the investigation of Mokaya’s devices. He admitted he was unaware of a High Court ruling requiring law enforcement to obtain judicial authority before compelling mobile service providers to release subscriber details.

He further admitted that he could not confirm the origin, source or geographic location of the disputed post.

He could not confirm whether the SIM card linked to the account had been properly registered. He had not recorded a statement from the complainant, President Ruto.

And crucially, when pressed directly, he conceded that the post in question did not actually contain a photograph of the President.

Safaricom employee Daniel Hamisi, who also took the stand, confirmed that he had released Mokaya’s details upon a written request from a senior police officer, without any court order having been presented or demanded.

His testimony crystallised what civil liberties advocates have long argued: that Kenya’s Data Protection Act of 2019 and the constitutional right to privacy exist on paper in a manner that is, in practice, subordinate to a phone call or a letter bearing a senior officer’s signature when matters touching on political figures are involved.

The magistrate was unsparing.

She found that police had failed miserably in their duty, that the accused had been framed, and that no direct evidence linked Mokaya to the alleged offence.

She noted that Mokaya’s social media account was shared with three other individuals who were never traced or called as witnesses, creating reasonable doubt that could not be resolved by the prosecution’s threadbare evidence.

She noted that the alleged offence was said to have been committed in Nairobi while Mokaya was physically in Eldoret.

She noted the complete absence of forensic or digital evidence tying him to the post. She observed that the court could not rule out the possibility that the post itself had been fabricated and planted on an account associated with his name.

She also noted something that ought to concern the leadership of the Safaricom corporation and its board.

The company’s compliance with an unlawful police request, without demanding judicial authorisation, may constitute a violation of the Data Protection Act.

That legislation imposes clear obligations on data controllers and processors regarding the circumstances under which personal data may be disclosed to third parties, including law enforcement.

Disclosure without a court order, in circumstances where one is legally required, is not a procedural technicality.

It is a substantive breach carrying potential regulatory consequences from the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner and civil liability in the courts.

Omari and Mutiso, who led Mokaya’s defence and who are no strangers to high-profile constitutional litigation, wasted no time in signalling what comes next.

They told the court after the ruling that they intend to sue the State for malicious prosecution. Legal analysts familiar with their track record consider this not an idle threat but a certainty.

A malicious prosecution claim would require establishing that the prosecution was initiated without reasonable and probable cause, that it was actuated by malice, and that it terminated in the accused’s favour. On the facts as found by the magistrate, all three elements appear to be richly available.

The civil suit, when filed, will almost certainly name Safaricom as a defendant or at minimum as a party from whom discovery is sought.

The company will need to account for its internal processes around law enforcement data requests. It will need to explain why its compliance team released subscriber data without demanding what the law requires.

It will need to address whether this was an isolated incident or systemic practice. These are questions that Safaricom’s corporate communications machinery cannot deflect with a press statement.

For Mokaya himself, the personal cost of this ordeal is not easily quantified.

He was charged on November 13, 2024, and the case dragged through a full trial over a period of roughly three months.

His lawyer told the court that the student could not even speak in the immediate aftermath of the ruling due to mental trauma and shock that had gripped him since his arrest.

He spent the duration of the case on a bond of one hundred thousand shillings or a cash bail of fifty thousand shillings, money that a finance student at a public university would not easily produce. His devices were confiscated. His movements were constrained. His studies were disrupted.

The broader significance of this case extends well beyond one young man’s acquittal.

It arrives at a moment when the relationship between digital speech, state power and telecommunications infrastructure is under intense scrutiny across Africa.

Kenya’s Data Protection Act was celebrated when it passed as a significant step toward aligning the country with international data protection standards.

The Mokaya case suggests that the legislation’s practical force remains weak in the face of political pressure and institutional habit.

When a senior police officer can write a letter to a telecommunications company on a Tuesday and have subscriber location data by Wednesday morning without a magistrate or judge having been involved at any point, the statute’s protections are nominal at best.

The Law Society of Kenya, through Mutiso’s involvement in the case, has effectively placed its institutional weight behind the argument that telecom companies must resist unlawful data requests regardless of who is making them and regardless of whose name appears in the underlying social media post.

That argument will now be tested in the civil courts, where Mokaya’s lawyers say they will press it with full force.

Safaricom has not issued a public statement on the matter at the time of publication.

The company, which controls the overwhelming majority of Kenya’s mobile subscriber market and whose M-Pesa platform is embedded in the economic life of tens of millions of Kenyans, has significant reputational exposure if the civil litigation proceeds and produces further uncomfortable disclosures about the ease with which law enforcement has historically been able to extract personal data from its systems.

The magistrate reminded police, in terms that deserve to be read widely, that the duty to observe the law does not diminish because the name of the President or any other powerful figure appears in a social media post.

She reminded them that cases of this nature must be handled with caution and free from public or political pressure.

She reminded them that the criminal procedure code and the Constitution are not suspended when someone posts something uncomfortable about a head of state.

For a twenty-four-year-old finance student from Moi University who spent months answering charges that a court ultimately found may have been built on a fabricated foundation, those reminders came at significant personal cost.

The question that will now occupy Kenya’s legal community is whether the institutions that failed him will be made to pay one.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoEx-Inchcape Kenya CEO Sanjiv Shah Charged With Bank Fraud

-

Development1 week ago

Development1 week agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoWaweru’s Bank Pockets Sh1.16 Billion from KPC IPO While Ordinary Kenyans Fled the Sale

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoNIS Kismu Hotel Secret Tape That Sealed Gachagua’s Fate and MP Ng’eno Death in A Chopper Crash

-

Investigations3 days ago

Investigations3 days agoSOLD TO THE BULLET: How the Bodyguard Handed MP Ong’ondo Were to His Killers

-

Investigations1 day ago

Investigations1 day agoHow Little-Known Pesa Print, Linked to State House Tycoons, Won NTSA Tender Worth Sh42 Billion in Traffic Fines

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoInvestor Sued Over Sh30,000 Fee to Access Runda Road

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoI Swore Never To Hire The Chopper Again, Author Recalls Harrowing Experience in Helicopter That Killed MP Ng’eno Alleges Poor Maintenance By Owners