News

Kenya Stares At Health Catastrophe As US Abandons WHO, Threatens Billions In Disease Fighting Programmes

The withdrawal plunges critical HIV, malaria and TB interventions into uncertainty as the country scrambles to fill a massive funding gap

Kenya is facing a potential health system collapse after the United States officially completed its withdrawal from the World Health Organisation on Thursday, a move that threatens to unravel decades of progress in fighting HIV, malaria, tuberculosis and other killer diseases.

The exit, which comes after 78 years of American membership in the global health body, has sent shockwaves through the Ministry of Health as officials grapple with the reality of losing the single largest source of international health funding at a time when disease burdens remain stubbornly high.

America’s departure from WHO, combined with sweeping cuts to bilateral health programmes including the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, represents what health experts are calling the greatest disruption to global health financing in living memory. For Kenya, the implications are nothing short of catastrophic.

The numbers tell a grim story. According to WHO records, the United States contributed a staggering 1.284 billion dollars, equivalent to 165.5 billion shillings, during the 2022 to 2023 funding cycle alone. This represented approximately 18 percent of the organisation’s total budget, making America the WHO’s financial backbone.

Dr Patrick Amoth, Director General for Health at the Ministry of Health, acknowledged the severity of the situation when he told Saturday Nation that the US departure represents a significant blow since America was the single largest contributor to WHO resources.

“It is a blow, but WHO has started the process of ensuring mitigation measures are in place by ensuring countries gradually increase their assessed contributions,” Dr Amoth said, though his words offered little comfort to health workers on the ground who are already seeing the effects of funding cuts.

The WHO had been supporting critical programmes in Kenya including reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, development of health products and technologies, non-communicable diseases, and communicable diseases. Their support, in Dr Amoth’s words, “has been broad.”

But the crisis extends far beyond WHO funding. The Trump administration’s simultaneous freeze on foreign aid programmes has effectively gutted PEPFAR, the largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease in history. Since its inception in 2003, PEPFAR has invested over 100 billion dollars in the global HIV response, saving 25 million lives and preventing millions of infections.

Kenya, identified as one of PEPFAR’s priority countries, now faces the terrifying prospect of its HIV treatment programmes grinding to a halt. Modelling studies paint a nightmarish picture. Research published in leading medical journals estimates that funding disruptions could result in 565,000 new HIV infections over the next decade in sub-Saharan Africa alone, with Kenya accounting for a significant portion.

Even more disturbing, analysis of the 90-day PEPFAR funding freeze earlier this year found that 71 percent of implementing partners reported cancellation of at least one category of activities, while 50 percent slashed staff numbers. The freeze was associated with an estimated 159,000 adult deaths from HIV in sub-Saharan Africa during that brief period.

Dr Abdourahmane Diallo, Director of Programme Management at WHO, warned that programmes likely to be affected include HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, neglected tropical diseases, immunisation, and emergency preparedness and response.

“Losing out on funding will bring major disruptions to the services being provided to countries. It jeopardises progress made to date and can compromise the scaling up of interventions that would be impactful,” Diallo said at a press briefing on Friday.

The impact cascades beyond health into Kenya’s broader economy. With the original African Growth and Opportunity Act framework having expired in September 2025, Kenyan exporters are operating under a fragile one-year temporary extension. Washington’s exit from the International Trade Centre, a body critical for technical trade assistance, signals diminishing appetite for supporting African exports.

If preferential trade access lapses later this year, Kenya’s textile and apparel sector will face an existential crisis. Industry analysts warn that reverting to standard tariffs could push costs for Kenyan goods entering the United States up by as much as 20 percent, rendering them uncompetitive against Asian rivals.

Kenya’s green energy grid and climate adaptation projects face similar jeopardy. The US withdrawal undermines market confidence required for carbon credit instruments that Kenya has banked on to finance major infrastructure. Projects dependent on Green Climate Fund disbursements may now face indefinite delays, pointing to a sharp contraction in government tendering in the coming fiscal year.

The withdrawal from health-focused multilateral bodies also presents a quieter but potentially massive liability for Kenyan employers. The executive order targets the UN Population Fund, a key driver of maternal health and gender programmes. Coupled with funding freezes to agencies supporting WHO mandates, the move threatens to reverse hard-won public health gains.

As donor funding recedes, the burden of healthcare financing will inevitably shift to the Kenyan exchequer and the private sector. Business leaders should brace for higher insurance costs and a hit to workforce productivity. A resurgence of communicable diseases or weakening of maternal health support will directly affect labour force availability.

Despite the WHO having anticipated this possibility following the Covid-19 pandemic, the organisation has been forced to slash 17 percent of its staff and implement dramatic efficiency measures. WHO Director General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has described the US actions as “sowing chaos,” threatening to roll back decades of progress on infectious and neglected diseases.

The withdrawal’s timing could not be worse. Eight of 12 WHO health priority areas in Africa were already funded at less than 50 percent earlier this year. Twenty-seven percent of all US funding through WHO for the African region goes to polio eradication, while 20 percent supports improved access to quality essential health services. The balance funds pandemic preparedness and response, capabilities that proved critical during the Covid-19 outbreak.

Dr Amoth has advised countries, including Kenya, to invest more in primary health care services, prevention, and health promotion, noting that such services are comprehensive, integrated, and promote inclusivity.

“Investing in PHC yields more dividends compared to investment in curative services,” he said, though critics point out that scaling up primary health care requires exactly the kind of international support that is now evaporating.

The Ministry of Health is awaiting communication from WHO on which specific programmes will be affected. Once that information arrives, officials promise to put in place necessary mitigation measures to ensure programme continuity. However, with WHO membership dropping from 174 to 173 member states and the remaining countries struggling with their own economic challenges, prospects for covering the funding gap appear dim.

Health experts warn that early detection of disease threats, a priceless gift in terms of pandemic response, will be severely compromised. As one American epidemiologist put it, responding to a five-acre fire is vastly different from battling a 5,000-acre inferno. Unfortunately, Kenya may now find itself facing the latter scenario when the next disease outbreak strikes.

The question haunting health officials across Kenya tonight is simple yet devastating. Will the country’s health system survive the withdrawal of its most powerful ally, or will millions of Kenyans pay the ultimate price for decisions made thousands of kilometres away in Washington?

For now, hospitals continue operating, antiretroviral drugs remain available, and malaria vaccines are still being administered to infants at facilities like Lumumba Sub-County Hospital in Kisumu. But those on the frontlines know that the clock is ticking, and without urgent action, Kenya’s hard-won health gains could vanish like morning mist over Lake Victoria.

The Ministry of Health has promised to provide updates as the situation develops, but for families relying on donor-funded health services, the wait is agonising. The slow bleed has begun, and only time will tell whether Kenya can stanch the wound before it becomes fatal.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Development5 days ago

Development5 days agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoHow Close Ruto Allies Make Billions From Affordable Housing Deals

-

Investigations9 hours ago

Investigations9 hours agoCity Tycoons, MD Under Probe Over Multibillion Kenya Power Tender Scam

-

Entertainment2 weeks ago

Entertainment2 weeks agoKRA Comes for Kenyan Prince After He Casually Counted Millions on Camera

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

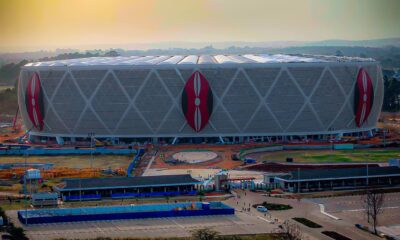

Investigations2 weeks agoTalanta Stadium Construction Cost Inflated By Sh11 Billion, Audit Reveals

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoAmerican Investor Claims He Was Scammed Sh225 Million in 88 Nairobi Real Estate Deal