Investigations

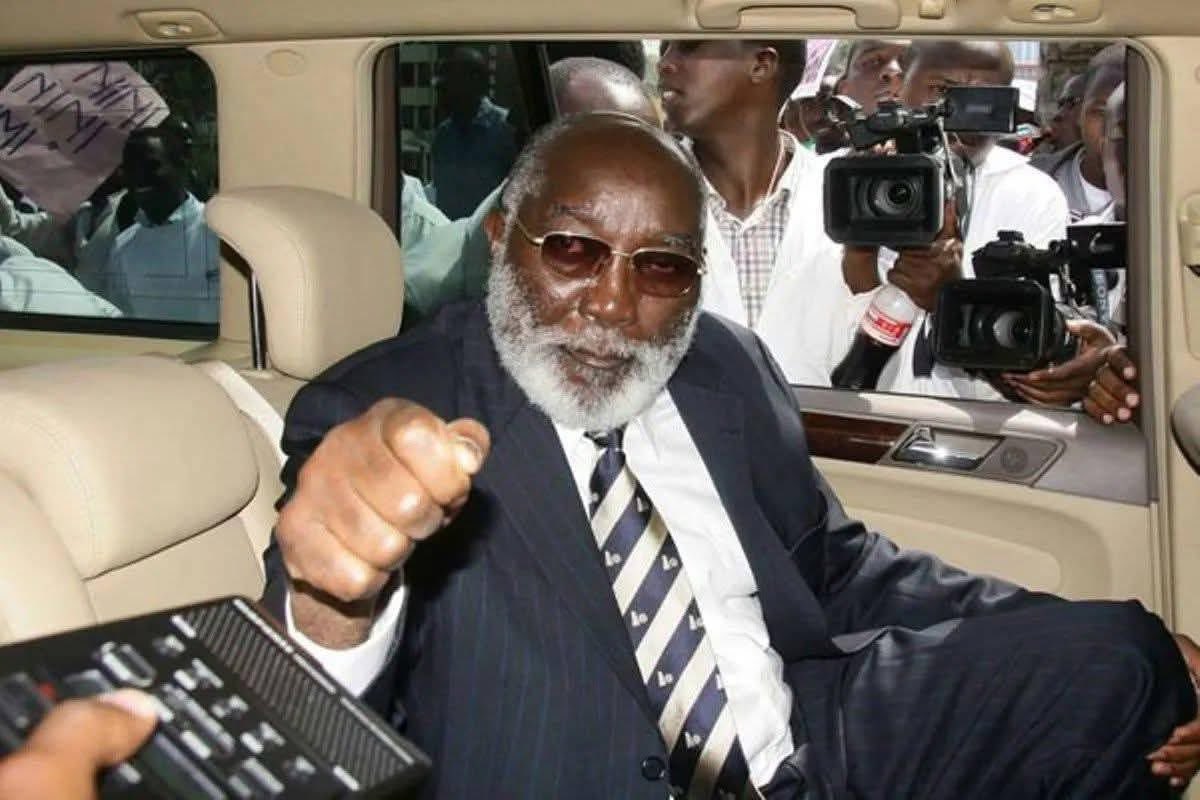

THE MAN WHO STOPS NATIONS: Inside The Enigma Called Harun Mwau

His personal net worth has been estimated at anywhere from $300 million to nearly $1 billion.

The courtroom fell silent on Thursday afternoon when Lady Justice Hellen Wasilwa pronounced the order that would throw Kenya into administrative disarray.

With a stroke of her pen, the recruitment of 10,000 police officers scheduled to begin the very next morning came to a grinding halt.

But the real story wasn’t happening in the courtroom.

It was happening in the whispered conversations across Nairobi’s corridors of power, where one name was being repeated in tones that mixed fear, respect, and something darker: John Harun Mwau.

“Boss,” as he’s known in certain circles, had done it again.

At seventy-seven years old, the man who once sued a sitting president and won, who was designated a drug kingpin by Barack Obama, and who has fought media houses to standstill in courtrooms, had just reminded Kenya of something it keeps forgetting: Harun Mwau doesn’t play by anyone’s rules but his own.

THE MAN WHO SUED MOI AND LIVED TO TELL THE TALE

To understand why Mwau’s name is spoken in hushed tones, you must go back to 1983, to the heart of the Nyayo era when Daniel arap Moi’s word was law and thinking the wrong thought could land you in Nyayo House torture chambers.

This was a Kenya where imagining the death of the president was literally treasonable, where dissent was crushed with an iron fist, where grown men trembled at the mention of Special Branch.

It was in this climate of fear that Harun Mwau did the unthinkable: he took President Moi to court and won.

The government had withdrawn his passport, claiming he was involved in “subversive activities.”

While others would have accepted their fate or disappeared into exile, Mwau marched into the High Court and successfully argued that his constitutional rights were being violated.

The court ordered the return of his passport. In Moi’s Kenya.

The audacity of it left legal minds dumbfounded and established Mwau’s reputation as a man who simply didn’t know fear or perhaps knew it too well and had conquered it.

THE PRESIDENTIAL BID AND THE FOOLSCAP GAMBIT

By 1992, the winds of multiparty democracy were blowing across Kenya, and Mwau, never one to miss an opportunity, threw his hat into the presidential ring.

He garnered a modest 10,449 votes, finishing far behind the major players. But losing wasn’t in Mwau’s vocabulary.

In a move that would become legendary in Kenya’s legal circles, he petitioned the High Court to declare him the only validly nominated candidate for president.

His argument? All other candidates, including Moi, had failed to present their nomination papers on the correct paper size foolscap, to be precise.

The case was dismissed, but the message was clear: Harun Mwau would find an angle where others saw none, exploit a loophole where others saw solid walls, and he would never, ever back down.

The Party of Independent Candidates of Kenya (PICK), which he founded, carried a motto that seemed to be his personal manifesto: “Think, Work, and Grow Rich.” And rich he certainly became.

THE EMPIRE IN THE SHADOWS

Mwau’s business empire is the stuff of legend and nightmare, depending on who you ask.

His personal net worth has been estimated at anywhere from $300 million to nearly $1 billion.

The Pepe Inland Container Depot in Athi River stands as his most visible but also most controversial asset.

Located strategically near the Nairobi-Mombasa highway, Pepe became the focal point of allegations that would eventually bring the full weight of the United States government crashing down on Mwau’s head.

He once held shares worth $10 million in Nakumatt, the retail giant that would later collapse.

He owned Charterhouse Bank.

His tentacles reached into real estate, security services, logistics, and shipping. But it was what allegedly moved through his container depot that made him infamous.

THE DAY OBAMA CALLED HIM A KINGPIN

June 1, 2011, is a date etched into Kenya’s political memory.

President Barack Obama, invoking the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act, named seven individuals as global drug trafficking kingpins.

Among them were two Kenyans: Naima Mohamed, known as “Mama Leila,” and John Harun Mwau, then the sitting Member of Parliament for Kilome.

President Barack Obama is photographed during a presidential portrait sitting for an official photo in the Oval Office, Dec. 6, 2012. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

The designation was devastating in its scope. Mwau’s assets in the United States estimated at $750 million were frozen.

Any American citizen or corporation doing business with him faced potential prosecution and jail time.

The U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control had built what they called a “foolproof” case, involving as many as ten U.S. government agencies that had been watching Mwau for years.

Adam Szubin, Director of the Office of Foreign Assets Control, was blunt in his assessment.

The designation stemmed from a 2004 incident when a container of cocaine worth approximately Sh6 billion was discovered at the Pepe container depot.

The U.S. government alleged that Pepe Enterprises was a transit point for narcotics, a way station in the global drug trade from South America through Africa and into European markets.

Mwau’s response was vintage Boss: total denial, claims of political motivation, and a defiant refusal to bow.

He characterized the designation as an attack by foreign powers seeking to destabilize Kenya’s political class.

He resigned from his ministerial position as Assistant Minister for Transport but retained his parliamentary seat. No formal charges were ever filed in Kenya.

The evidence that the U.S. claimed was ironclad was never shared with Kenyan authorities. Mwau remained free, and his businesses, at least those in Kenya, continued to operate.

THE MEDIA WARS

Between 2004 and 2005, Mwau went to war with Kenya’s media houses, and it was a war he fought with the same ruthless efficiency he brought to business and politics.

When the Nation Media Group published articles linking him to tax evasion scandals and drug trafficking, Mwau didn’t just sue he filed multiple suits against senior executives and editors, seeking to permanently bar the media from publishing anything about his business dealings.

The cases dragged through the courts for nearly two decades, only being resolved in 2024.

Mwau’s strategy was clear: make it so expensive, so legally complicated, and so personally threatening for journalists to write about him that they would simply stop. To a large extent, it worked.

Coverage of Mwau became sparse, careful, hedged with legal caution. The man who once courted publicity now operated best in the shadows.

THE OLYMPIC SHOOTER

Lost in the controversies is a detail that seems almost quaint: before he was a businessman, a politician, or a designated kingpin, John Harun Mwau was an athlete.

He competed as a sports shooter at both the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City and the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich.

It’s a biographical footnote that speaks to a different time, a younger man with different ambitions. But even then, one imagines, he was learning to aim carefully, to hold steady under pressure, to hit targets others missed.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL GAMBIT

Which brings us back to October 2, 2025, and the police recruitment crisis.

Mwau’s petition isn’t about police recruitment at all not really. It’s about power, about who wields it, and about the interpretation of constitutional authority.

His argument is technically sophisticated: the National Police Service Commission, he claims, is not a national security organ under Article 239(1) of the Constitution and therefore lacks the authority to recruit officers.

That power, he argues, belongs exclusively to the Inspector General and the National Police Service itself.

Is he right? The courts will decide. But right or wrong, Mwau has once again inserted himself into a national conversation, halted a government initiative, and reminded Kenya’s political class that he remains a force to be reckoned with.

The thousands of young Kenyans who were preparing to report for recruitment on October 3rd are now in limbo, their futures hanging on the outcome of a legal battle initiated by a man most of them have probably never heard of.

THE QUESTION NOBODY ASKS

Here’s what makes Harun Mwau truly frightening to those in power: he understands the system better than the people running it.

He knows that in Kenya, as in most places, the law is both a shield and a weapon, and he has mastered the art of wielding both.

He knows that institutions are only as strong as the people defending them, and that bold action often succeeds simply because nobody expects it.

People speak of him in hushed tones not because he’s a criminal the U.S. designation notwithstanding, he’s never been convicted of anything in Kenya but because he represents something more unsettling: proof that the rules everyone else follows are actually optional, if you’re smart enough, rich enough, and brazen enough.

He sued a dictator and won. He ran for president on a technicality. He built an empire that allegedly facilitated global drug trafficking and walked away with barely a scratch. He fought media houses to a standstill.

And now, at seventy-seven, he’s halted the recruitment of 10,000 police officers with a constitutional argument.

The question isn’t whether Harun Mwau is guilty or innocent of the things he’s been accused of over the years. The question is whether Kenya, or any country, can function when individuals understand the system so thoroughly that they can bend it to their will. Mwau is either the ultimate expression of legal acumen and constitutional rights, or he’s proof that our systems are built on foundations far more fragile than we’d like to admit.

On October 21, when the case comes up for mention and compliance, Kenya will get another chapter in the saga of the man they call Boss.

Whether he wins or loses this particular battle is almost beside the point. John Harun Mwau has already won something more valuable: immortality in Kenya’s political folklore as the man who never backs down, never shuts up, and never, ever plays by the rules everyone else follows.

And that, more than any court ruling or government designation, is why they speak his name in whispers.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoEastleigh Businessman Accused of Sh296 Million Theft, Money Laundering Scandal

-

Investigations7 days ago

Investigations7 days agoInside Nairobi Firm Used To Launder Millions From Minnesota Sh39 Billion Fraud

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoMost Safaricom Customers Feel They’re Being Conned By Their Billing System

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoUnfit for Office: The Damning Case Against NCA Boss Maurice Akech as Bodies Pile Up

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoEXPLOSIVE: BBS Mall Owner Wants Gachagua Reprimanded After Linking Him To Money Laundering, Minnesota Fraud

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTax Payers Could Lose Millions in KWS Sh710 Insurance Tender Scam As Rot in The Agency Gets Exposed Further

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPastor James Irungu Collapses After 79 Hours Into 80-Hour Tree-Hugging Challenge, Rushed to Hospital

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoDeath Traps: Nairobi Sitting on a Time Bomb as 85 Per Cent of Buildings Risk Collapse