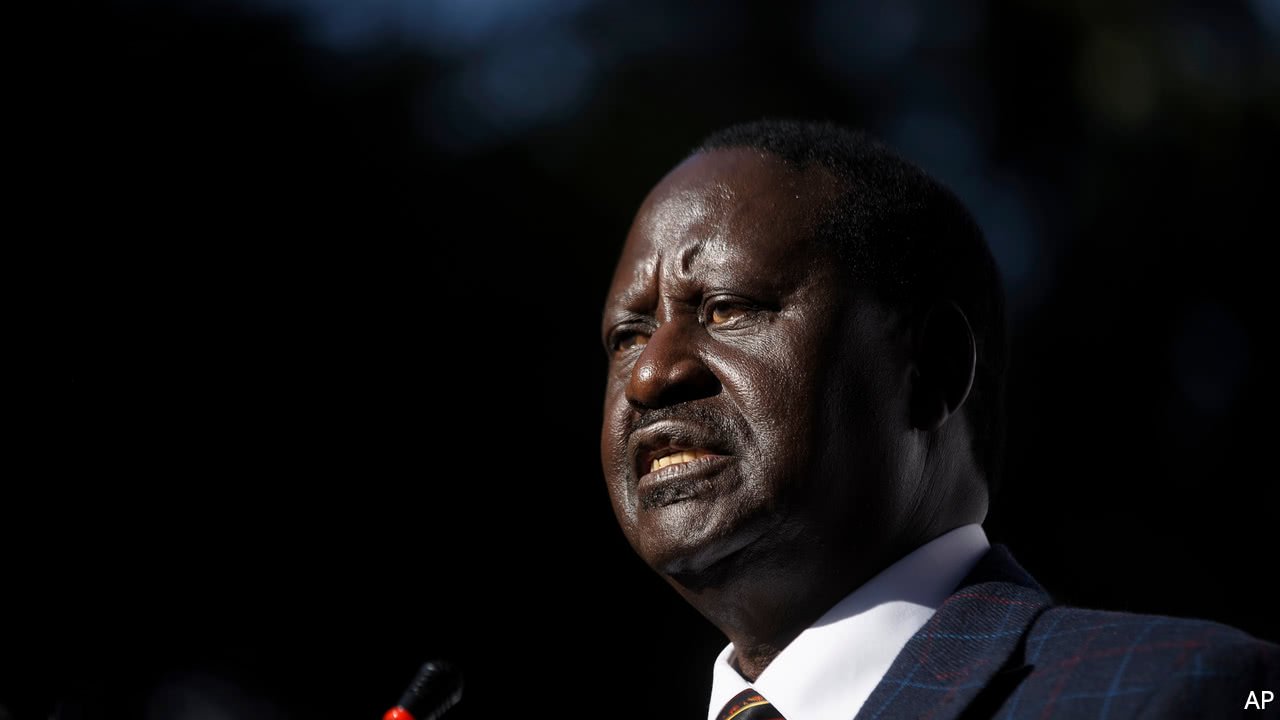

In a surprising turn of events, Raila Odinga announced on October 10 that he was withdrawing from the scheduled October 26 rerun of the 2017 presidential election. In September, the Supreme Court of Kenya held, by a 4-2 majority, that the original August 8 election was invalid because it was not held to the standard required by the law, granting Odinga a second shot at the presidency.

Superficially, Raila withdrawing from the polls with barely a fortnight to go would seem like a tremendous waste of political momentum for him personally, and the country’s time, money and energy more broadly.

However, upon examining the myriad of laws, regulations and court decisions that govern the election process in Kenya, the net effect of Raila’s decision may be effectively extending the election timetable – buying both his coalition and the Independent Election and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) more time.

Raila may also have thrown open the presidential rerun to more candidates than the two envisaged by the IEBC.

To understand how this works, we need to read the various pieces of Kenya’s election law scattered across five documents – the 2010 constitution, the 2013 Supreme Court decision on the presidential election, The Elections Act, Kenya’s election regulations on elections, and the majority decision in the 2017 election petition.

Kenya is highly unusual in that some very detailed provisions of the election law are contained in the Constitution, and meaning if there is a clash between the Constitution and any other subsidiary law – for example – the elections regulations, the Constitution prevails. Specifically, Article 138 of the Constitution contains detailed rules on how elections must be conducted and when. It also has a provision that if only one candidate is nominated for the presidency, he or she can be sworn in as president.

But, because of the way the Supreme Court interpreted Article 138 in 2013, the June nominations for the 2017 polls are still valid for an October 26 election, which means that Uhuru Kenyatta cannot be automatically announced the winner. He is technically not running uncontested and a fresh election has to happen. The question for the IEBC is when this new election happens.

Secondly, the 2013 Supreme Court decision also held that if one candidate withdraws from a fresh election triggered by an invalidated petition – as is the current case – then the entire clock starts over and all candidates must seek fresh nominations. The initial 60-day deadline triggered by the September 1 decision is suspended and the rerun of the election goes back to the calendar set out in the elections act and the election regulations. This process also opens the door for other candidates who did not contest the August 8 election or who were excluded by virtue of conceding the invalidated poll. Basically, under this law, Kenya’s election calendar starts from scratch because of Odinga’s withdrawal.

Representatives of the ruling Jubilee coalition argue that Regulation 52 of the Kenya General Elections means that Odinga’s withdrawal is invalid. That regulation says that a candidate has to withdraw their nomination within three days of submitting it. Under the 2013 decision, candidates participate in a rerun on the basis nomination certificates they already held. Jubilee is arguing that for Odinga’s withdrawal to be valid, he would have had to submit it in June of this year and they want the October 26 election to go ahead with Odinga’s name on the ballot, even if he does not contest.

But this argument is undercut by a simple principle of legal interpretation on the hierarchy of laws. The election regulations are statutes and if there is a clash between a statute and a Supreme Court decision – particularly on the interpretation of the Constitution – the Supreme Court decision holds. In this case, if there is a clash on what fresh nomination means, the IEBC should be guided by the Constitution and the 2013 decision, as well as any other existing Supreme Court jurisprudence – not the regulations. And the 2013 Supreme Court decision clearly states that if a candidate withdraws from a fresh election after an invalidated election, then all parties return to the process of nomination.

Some lawyers are arguing that because the Supreme Court provided an interpretation of article 138 in response to a request from an amicus curiae brief from the attorney general, rather than in response to a question from a petitioner, then paragraph 290 isn’t binding judicial precedent. Basically, they argue that court was giving an opinion “by the way” rather than in response to a serious legal question. But prior to the 2017 petition, many of the same lawyers argued the inverse – that the entire decision was binding and that the court should exercise restraint in amending it. The IEBC lawyers will give their own interpretation later today, but ideally, they should seek direction from the Supreme Court.

In effect, the text of the law is that Odinga’s candidacy should cancel the October 26 election and trigger the reopening of nominations for the presidential election. This would give the IEBC more time to prepare and allows for other candidates to join the race.

But this would not go to the heart of some of Odinga’s demands – the “irreducible minimums” – as a precondition for participating in the election. Significantly, because Uhuru Kenyatta remains incumbent under Article 134 of the Constitution, he cannot approve the appointment of new members of statutory commissions like the IEBC. An overhaul of the commission under the current law remains unlikely.

Still, Odinga’s decision does not mean Kenyatta can be automatically sworn in as president – the invalidation of the August 8 election means that the election did not happen and the process of electioneering still needs to happen on a date prescribed by the IEBC. Kenyatta’s Jubilee coalition maintains that the October 26 poll must go on as scheduled, but given the existing legal framework, a new poll date seems inevitable.

Overall, Kenya is deep into uncharted territory – testing every nook and cranny of the country’s election law. For the long game of democratic consolidation, this is good, as long as the various actors act within the confines of the law. But this situation also points to an overarching problem with that law: Kenya’s election law is simply too complicated. It is unwieldy – unnecessarily so – primarily to accommodate the many paranoias of the country’s leading political figures. One shouldn’t need a law degree, a high-powered printer and an afternoon off in order to understand every single political decision taken during an election cycle.

Thankfully, there is a bench of seven individuals burdened precisely with this task. To avoid throwing more ambiguity at an already convoluted process, the IEBC should seek an advisory opinion from the Supreme Court, clarifying how to read the various pieces of election law together and charting the best way forward.

Nanjala Nyabola is a writer and political analyst based in Nairobi, Kenya.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

Article originally appeared on Al Jazeera.