Business

The Crash of Koko Networks: A Detailed Look Into How and Why It Happened, And The Potential For A “Silver Lining” For Carbon Integrity

The problem lay in how Koko exploited the now-closing gaps in how carbon credits are generated.

By Tom Price

As the news of Koko Networks’ bankruptcy sank in over the weekend, a false narrative was created that this was somehow the fault of Government of Kenya regulators, for failing to approve the sale of Koko’s carbon credits.

While that may have been the trigger, if anything that decision is a silver lining in this tragedy, showing that the system for ensuring high quality carbon credits is starting to work as intended.

Regulators aren’t rubber stamps – and in the case of Koko, the Government of Kenya did their job exactly right, enabling carbon credits to exist alongside Kenya’s other high quality exports like tea and coffee. And that’s because Koko’s carbon credits were largely hot air, and the failure of Koko to sell their offsets was entirely of their own making.

Before explaining why, first a moment of compassion for the victims here: the customers, employees, investors, lenders, and other partners who thought they were supporting a clean cooking fuel company rather than a flawed carbon credit company, and were misled by Koko’s leadership team.

To their credit, they built Koko into a world class operation, run by some of the smartest, most capable operators available in business today; other companies will be lucky to snap them up.

Koko was incredibly impressive, a marvel of technology and branding meeting a market ripe for disruption.

The stoves worked well, the fuel was clean and affordable, and the fuel ATMs were convenient and modern. And the need to replace dirty, unsustainable charcoal is as pressing as ever. The fatal flaw for Koko was the heart of their operation: how they counted carbon credits.

A business model built on carbon

That’s because making and selling carbon credits was the entire business. As they told the Harvard Business Review, Koko subsidized their fuel by 25-40% and their stoves by up to 85% – they lost money on every customer they signed up, and every liter of fuel they sold. And if their claims are to be believed, they were selling upwards of ~20 million liters every month at the end, losing money on every single one. So the only way to break-even – let alone profit – was carbon credits.

The problem lay in how Koko exploited the now-closing gaps in how carbon credits are generated. Koko has to date been issued almost 15 million carbon credits by Gold Standard, at least 170,000 of which have been sold to companies like Bank of America and Bristol Meyers. But those were sold into the voluntary market, which generally commands lower prices. The real money was in the compliance market, like CORSIA which covers airlines.

According to Gold Standard and Koko’s own documents, Koko expected to earn as much as 5+ carbon credits per customer per year for ten years – far, far more than other companies in the same market. These carbon credits, generating $100 in revenue per customer per year, would be used to repay the cost of the stove and the fuel subsidy and then generate operating profit for the company.

This carbon finance would therefore be used to provide a clean transition from cooking with dirty fuels, return a profit to investors and provide the company with healthy margins to continue expansion.

Why was this approach doomed to fail from the start? There are three fatal flaws in Koko’s approach, lessons that must be learned for the sector to build back better.

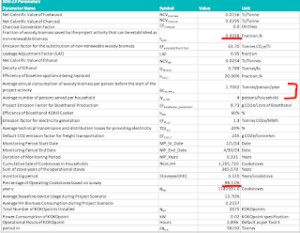

1 – Overcounting their sustainability. Koko used a wildly inaccurate fNRB (the fraction of non-renewable biomass, or the modeled rate at which trees won’t grow back after cutting them down to make charcoal). Koko claimed 93%, when in fact fNRB in Kenyan cities like Nairobi is 38%. The inaccuracy of Koko’s assumption has been widely known and discussed for some time. Koko, like most other project developers, opted against using scientific studies and instead chose a figure that would maximise the amount of savings they can claim.

That metric alone would result in overcredited Koko by 2.4X.

2 – Overcounting their impact, with a vastly distorted and inaccurate claim of baseline fuel usage. Koko claimed all of their urban customers in cities like Nairobi were previously using only charcoal (6.8 tons of firewood equivalent, or about 1 ton of charcoal per household per year), and none used any LPG, and that they all used their Koko stoves all the time instead.

Any credible survey shows that is simply not true. “Fuel stacking” (cooking with multiple fuels alongside one another) is the default, not exception, and LPG use is widespread among households in urban Kenya.

At the start of their staggering growth, 52% of households in urban Kenya were already using LPG (2019 census ref, table 2.18, page 330). In Nairobi, the urban area where Koko expanded the fastest, the number was at 67.2%. The logic that all of the customers onboarded were solely non LPG customers is simply not credible. Yet Koko claimed that all ~1.3 million customers were using *only* dirty charcoal before switching to ethanol.

That would overcredit them significantly, compounding their fNRB overcrediting.

From Koko’s Gold Standard documents, GS 11440. Citation: GS11440_ER Sheet_MP07_VPA2_V03_20.01.2025.xlsx. Dated March 2025. Full documents available here.

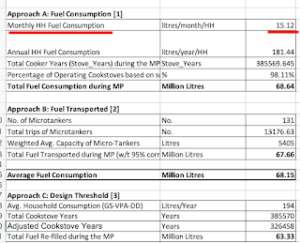

3 – Overcounting how much clean fuel their customers were actually using. This is perhaps the most egregious metric. Koko was a walled garden system – you could only fill their stoves with their tanks, which you could only top up in their fuel ATMs, and only after you punched in your personal customer ID.

They knew exactly, to the liter, how much each customer was buying every month, and there was every incentive to report that number … if it would be higher than the claimed average.

But they didn’t.

Instead, they used an average of 15+ liters for every customer, every month, “verified” most recently by surveying only 159 customers out of almost 900,000 households in March 2023.

There’s a simple way to know what actually happened – they have the data, they just didn’t use it. And the most obvious reason why is also the most likely one.

These three metrics alone account for substantial overcrediting, with some estimates suggesting as much as 10X (without actual fuel sales data, we may never know).

Academic experts weigh in

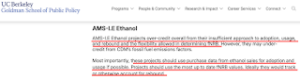

The concern about what a company like Koko was doing was explicitly laid out in research by UC Berkeley in January, 2024, in ground breaking work which for the first time took a comprehensive look at the over/under crediting in the global cookstove market.

The researchers examined every methodology and input metric in detail, including the methodology Koko chose and how Koko chose to interpret the rules. Literally every concern they raised about potential overcrediting was something Koko had chosen to do.

The attention surrounding the research accelerated calls for reform, and pretty soon the clock for Koko was ticking. Tough new rules were coming into place, like those by Gold Standard and UNFCCC that would come into effect in January 2026 requiring the use of an accurate fNRB.

So the race was on to get those credits sold, and that required Kenya to sign off on a Letter of Authorization.

A changing market

Some background may be in order. Not all carbon credits are the same. Early methodologies relied largely on insufficient sampling and estimates, which UC Berkeley pointed out was rife with overcrediting. To its credit, the cookstove sector has responded, and now projects that can prove their use and impact, such as through tracking fuel sold or stove use, are seen as more credible. The Gold Standard’s accurate new “Metered and Measured” methodology is widely seen as most reliable, and the new CLEAR methodology has helpfully incorporated approaches relying on continuously-tracked energy consumption (CTEC).

But as the market continues to move towards quality and tougher standards, outdated methodologies are still used by legacy projects. Koko has chosen to continue using one of the worst rated methodologies (AMS-I.E), for perhaps the simple expedient that it was in their best interest.

This is not to discount the challenges for developers as standards change, but it has now been almost three years since the pre-print of the UC Berkeley research became public, and concerns about overcrediting have been constant in the last years.

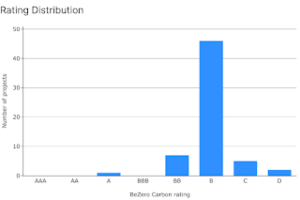

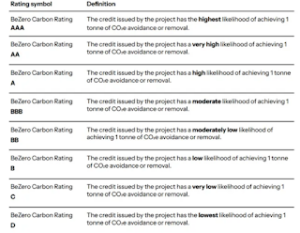

This duality is what has created the market opportunity for the rise of ratings agencies like BeZero, which independently evaluate carbon projects on objective standards, and then rate them from AAA-D depending on quality.

Here’s how cookstove projects stacked up last year, by rating:

When Koko was rated, they earned only a “B” overall grade, which means “the credit issued by the project has a low likelihood of achieving 1 tonne of CO2 removal.” And they got an even lower “D” on the sub-metric for carbon accounting.

Since they chose not to use more credible metrics and earn a higher rating, their only hope was to find large buyers who either wouldn’t know enough, or wouldn’t ask before buying the offsets – or simply didn’t care about quality.

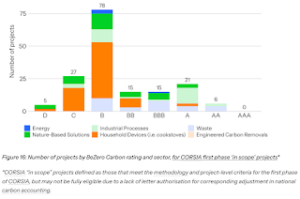

For a while that market seemed like CORSIA, the program for airlines to offset their emissions. And while CORSIA had their own standards, they weren’t nearly tough enough – check out just how poorly rated all the CORSIA eligible projects are:

Crash Out

Which brings us back around to the Government of Kenya’s refusal to issue Koko a letter of authorization to sell into the CORSIA market. According to reporting by QCINTEL, Kenya’s National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) wanted Koko to amend their fNRB to be more accurate, and Koko refused. Kenya needed the carbon credits it approved to be valid, since it would impact their ability to meet their Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris climate accords. Koko’s approach to over-crediting meant they requested an outsized number of authorizations from the country’s entire budget for all projects, industries and years.

And reportedly attempts to work with Koko to use more credible approaches so that the Kenyan Government could safely authorize a smaller volume within their national budget were rebuffed by the company, unwilling to be reasonable.

By refusing to use credible numbers, Koko chose their own fate. There can be no more damning indictment than of them being willing to let the company go out of business (and try to blame regulators in hopes of claiming an insurance settlement from MIGA) than to play by the rules and be accurate. They crashed out instead of coming clean.

Plenty of blame to go around

Koko is not alone in blame here. These fundamental flaws in the business model link back to larger flaws within the system.

- Standard bodies and verification bodies

Gold Standard, which issued almost 15M carbon credits to Koko, has some tough questions to answer about why they continued to let projects use significantly divergent fNRB rates at the same time in the same market, and why a company like Koko was allowed to choose an estimate of usage, even though Koko had all the data needed to prove it.

Meanwhile, the independent verifier hired by Koko signed off on millions of credits based on ~150 surveys of customers picked by Koko out of their ~900,000 total customer population. Why was the company not challenged to provide actual fuel sales data?

(On a more positive note, it is helpful to see Gold Standard’s recent methodological updates – including both overall as well as to its suite of cookstove methodologies – to align with the Paris Agreement, introduce greater scrutiny on data used and increase the hurdle rate on what qualifies as a GS VER.)

- Koko carbon and commercial leaders

The leadership at Koko who set up, generated and sold carbon credits under false pretenses have to accept responsibility for the choices they made. All of this was being debated publicly and widely. None of these issues were a secret or a surprise. So it’s difficult to find another way to interpret the design of the carbon program they oversaw, and the data they chose to report, other than that at some point along the way they realized their mistakes and yet continued to knowingly mislead stakeholders about the veracity of their carbon claims, in hopes of a big payout. Estimates are Koko was on track to eventually issue almost $1B in carbon credits.

- The investor community

Investors appear to have missed key items during their due diligence on this business. All their workings are readily accessible in the public domain. It only takes someone with a few hours on their hands to unpack what is being stated and walk outside and check those assumptions with reality. If they couldn’t check reality, they could have at least referenced the latest science, and compared it to Koko’s claims.

For example, the MIGA due diligence report is publicly accessible. The publicly-available key documents and scope of review don’t appear to have reviewed the actual carbon programme they were insuring against.

How the industry moves forward

The tragedy of all of this is that while the business model of using carbon to enable broader clean cooking access is fundamentally sound, Koko’s overwhelming reliance on only that revenue while deeply subsidizing their fuel sales was fatally flawed from the start.

In Kenya, unsubsidised ethanol cooking fuel is the most expensive method to cook any meal (link to CCT paper). The notion that a perpetual carbon subsidy should cover the negative operating margin was always going to meet reality at some point in time, no matter how much good PR they received.

Koko was an incredibly well run operation, delivering real value and benefit to customers. Perhaps they could have charged a higher price for the fuel, reducing risk exposure. Or maybe if they had aimed to earn fewer credits but gotten a higher price for them, they could have made it work. In recent months, there has been a very clear trend towards projects with higher ratings earning a multiple of the value of lower rated ones.

That makes sense – to use an analogy, if carbon credit buyers are purchasing bottles of water, they don’t want the container, they want the content. A ton of emission reductions should be a provable ton of emission reductions. If you can prove it, you should be paid more. And if you can’t prove it, then you should sell at a discount, if at all. Koko tried to have it both ways – selling a water bottle labeled as “full” but with only a few drops at the bottom, trying to get premium pricing for a substandard product.

The good news is that tools now exist for all cookstove projects to prove their impact, through logging fuel sales or incorporating stove use monitors.

The urgency is greater than ever. Cooking with firewood and charcoal adds more CO2 emissions than the entire global aviation industry, while hundreds of millions of families suffer the health impacts of smoky kitchens.

Ratings agencies will play a vital role in birthing this new market of integrity. There are now multiple “A” rated cookstove projects, delivering real provable impact, while lowering costs and improving health.

Koko could have been one of those. Instead it will be remembered for two things: the company that tried to pull off another great carbon heist, and the bravery of the Government of Kenya regulators who stood up for the integrity of their market.

Anything else is just hot air and victim blaming.

The above images and data are all taken from publicly available information, mostly by Koko to Gold Standard; will happily update or amend if/when better information is available.

The author has eight years’ experience in the clean cookstove sector, most recently with EcoSafi, with a focus on carbon credit integrity. The author is no longer affiliated with the company, and the views expressed are personal, offered in the public interest to support informed debate on carbon finance for cookstoves.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy

-

Economy1 week ago

Economy1 week agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Grapevine6 days ago

Grapevine6 days agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Africa2 weeks ago

Africa2 weeks agoFBI Investigates Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s Husband’s Sh3.8 Billion Businesses in Kenya, Somalia and Dubai

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTragedy As City Hall Hands Corrupt Ghanaian Firm Multimillion Garbage Collection Tender

-

Arts & Culture2 weeks ago

Arts & Culture2 weeks agoWhen Lent and Ramadan Meet: Christians and Muslims Start Their Fasting Season Together