News

The Billionaire Refugee, the Glock Pistol, and the Shadow of Al-Shabaab

How a Turkish tycoon who built courthouses and shot a teenager in the same county now faces terrorism charges linking him to East Africa’s deadliest terror network. The questions Kenya has been slow to ask.

On the evening of January 12, somewhere between Vipingo and Kikambala on the rain-slicked Mombasa to Malindi Highway, a Toyota Land Cruiser V8 and a convoy of Orange Democratic Movement politicians collided in more ways than one. By the time the dust settled, two Turkish nationals were in custody, a Glock pistol had been seized, and within forty-eight hours, the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit was before a Mombasa court alleging links to one of the most feared terror organisations in the Horn of Africa. What began as a road rage incident had morphed into what the Kenyan State now describes as a terrorism case of the highest order. The Standard has spent weeks piecing together the full story of Osman Erdinc Elsek, and what it reveals is far more unsettling than a single night on a dark highway.

Elsek is not an unknown quantity in Kenya. For nearly two decades, he has been a fixture along the Coast, a man who built affordable housing estates, constructed parts of courthouses, partnered with Eco-Bank on mortgage schemes, and claimed investments worth over six billion shillings. He is, by his own telling and by the corporate branding of his Elsek Group Conglomerate, a benefactor. He is also, according to the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, a member of Al-Shabaab.

“The terrorism allegations directly contradict the police’s own records. This is purely a traffic accident in which I was the victim.”

The charge sheet presented before a Mombasa court on Monday, February 2, is a six-count document that lays bare the scope of what investigators have assembled. In the first count, the prosecution alleges that Elsek was a member of Harakat Al-Shabaab Mujahideen, the full formal designation of the terrorist group that carried out the 2013 Westgate Mall attack in Nairobi, killing 67 people, and the 2015 Garissa University massacre that claimed 148 lives. In the second and third counts, investigators claim that a Samsung Flip 7 phone recovered from Elsek contained video recordings with titles referencing Osama bin Laden and bearing the hallmarks of jihadist propaganda. In the fourth count, he is accused of unlawfully possessing a Glock pistol, serial number RBV973. The fifth charge sees his associate, Gokmen Sandikci, accused of consorting with an armed man. The sixth and final count, added nearly twenty days after the initial arrest, accuses both men of assaulting Boniface Katana on the night the whole saga began.

For a man who claims to have built parts of the Shanzu courthouse where he once stood trial, the irony of now facing the court’s judgment on terrorism charges is not lost on observers. But it is the Glock pistol, serial number RBV973, that keeps appearing at the centre of this story, and it is where the pattern becomes difficult to ignore.

- Oct 2020 Seized from Elsek after he shot 15-year-old Frank Omwenga in the chest during an altercation following a football match in Kilifi. Police impounded the pistol along with 15 rounds of 9mm ammunition. Elsek’s civilian firearm licence was also held.

- Jan 12, 2026 The same Glock pistol, same serial number, same 15 rounds of ammunition, recovered from associate Gokmen Sandikci during the arrest of both men in Mtwapa, Kilifi County.

- Jan 14, 2026 Elsek tells the Mombasa court that the firearm is lawfully licensed and that his possession of it is entirely legal.

- Feb 2, 2026 The DPP formally charges Elsek with unlawful possession of the firearm, alleging it was intended for use in a manner prejudicial to public order.

In October 2020, Elsek was arrested at Kilifi Police Station after shooting a teenager named Frank Omwenga, who was fifteen years old, in the chest during a street scuffle. Police filed the report at Kijipwa Police Station. The Glock was confiscated. Elsek’s civilian licence was surrendered. The case attracted media attention, drew public outrage on social media, and then, as so many cases involving wealthy individuals in Kenya tend to do, it faded quietly from public discourse. The Standard found no record of a successful prosecution arising from that shooting.

Now, five years later, that same pistol, identified by the same serial number, is back in police custody. This time it was found in the possession of Sandikci, not Elsek. The prosecution has not yet explained publicly how a firearm that was impounded in 2020 came to be in the hands of a man travelling with Elsek in 2026. The defence, for its part, has insisted the weapon was lawfully re-licensed. The court has yet to rule on the matter.

A Refugee With Six Billion Shillings

To understand how Osman Erdinc Elsek ended up in a Mombasa courtroom facing terrorism charges, it is necessary to understand the unusual shape of his life in Kenya. Court records and official filings paint a portrait that defies easy categorisation.

Elsek arrived in Kenya in December 2008. According to his own statements in court, he came after falling out with the then Turkish president. He was granted refugee status by the Kenyan government, a designation that typically applies to individuals fleeing persecution, war, or serious threats to their safety. He settled in Kikambala, a coastal town in Kilifi County, and began building.

Through the Elsek Group Conglomerate, he registered eighteen companies in Kenya operating across construction, real estate, hospitality, quarrying, transport, production, and mortgage banking. The company’s own website boasts of projects across East Africa including housing estates in Kikambala, a tourism university in Rwanda, and a consulate building in South Sudan. The firm partnered with Eco-Bank to offer mortgage financing and displayed model houses at trade expos in Mombasa. By the time he stood before the court in January 2026, Elsek claimed property worth more than six billion shillings, all invested in Kenya.

A refugee with billions. A man who built courthouses and appeared before them. A philanthropist who shot a child. The contradictions in Elsek’s story are not new. They have been present for years, quietly accumulating like sediment, and it is only now, with the terrorism charges, that the full weight of the file is being examined.

The Night on the Highway

The events of January 12 have been told differently by each side, and the version of events matters enormously to how the terrorism charges are understood. The ODM party had concluded a Central Management Committee meeting at Vipingo. A convoy of party leaders, which included Wajir Governor Ahmed Abdullahi Jiir, was making its way towards Moi International Airport in Mombasa when, according to police and multiple witnesses, a vehicle driven by one of the Turkish nationals cut aggressively into the convoy and struck the governor’s car from behind.

What happened next has become the subject of fierce legal contest. Police sources and the initial reports indicate that Elsek alighted from his vehicle, drew a firearm, punched the governor, and slapped his driver. The Council of Governors issued a furious statement demanding to know who had authorised a foreigner to carry a gun along Kenyan roads. Interior Cabinet Secretary Kithure Kindiki ordered a probe.

Elsek’s account is starkly different. In a sworn affidavit, he states that he was the one hit from behind, that the governor’s convoy fled the scene, and that when he gave chase and confronted the occupants, he was assaulted. He claims the convoy members attempted to beat him using their own firearms. He says he identified the governor only afterwards, and that the governor subsequently threatened him with deportation.

The truth of what happened on that highway may eventually emerge through the courts. But what is remarkable is how quickly the narrative shifted from a road rage incident to a terrorism investigation. Within hours of the arrest, the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit was involved. Within a day, the State was before a court alleging terrorism financing. Within three weeks, the DPP had approved a charge sheet alleging Al-Shabaab membership.

“I believe the terror allegation is an afterthought, politically instigated, wild and malicious, manufactured and aimed at unlawful detention.”

The Propaganda Videos and the Phone

The terrorism charges hinge in significant part on what was allegedly found on a Samsung Flip 7 mobile phone recovered from Elsek. The charge sheet states that the phone contained video recordings that constitute articles connected to the commission of a terrorist act. The titles cited in the charge sheet include content referencing Osama bin Laden and phrases characteristic of jihadist recruitment material.

The prosecution has framed these videos as evidence that Elsek was knowingly collecting information intended for use in terrorist activities. The offence, the State says, was committed on January 14 at the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit offices at Mombasa Police Station, the same location where Elsek was being held at the time.

The defence has not yet publicly addressed the content of the videos in detail, focusing instead on the procedural defects in the charge sheet. In the hearing on February 2, Elsek’s three advocates raised a preliminary objection arguing that the first count, alleging Al-Shabaab membership, failed to specify a date, time, or location. They argued that without these particulars, the charge was fatally defective and that proceeding on it would amount to a miscarriage of justice.

The prosecution countered that the absence of a specific date did not mean that no offence had been committed, and that investigators were entitled to add charges as they emerged during the course of an investigation. The magistrate is expected to rule on whether the charges will stand on February 3.

Al-Shabaab and the Money Trail

To appreciate the gravity of the charges against Elsek, it is necessary to understand the scale of the threat that Al-Shabaab poses and the sophistication of its financial operations. The United States Department of Treasury has repeatedly sanctioned networks of businesspeople across the Horn of Africa, the UAE, and Cyprus who have been identified as financial facilitators for the group. In 2024 alone, the Treasury designated sixteen entities and individuals comprising a money laundering network that funnelled funds to Al-Shabaab through business fronts in Kenya, Uganda, Somalia, and Cyprus.

Al-Shabaab generates between one hundred million and two hundred million dollars annually. A West Point counterterrorism assessment published in 2025 identified the group as al-Qaeda’s wealthiest affiliate in the world. Its funding streams include extortion of local businesses, taxation of imported goods, smuggling, trade-based money laundering, and the exploitation of hawala money transfer systems. The US State Department has placed a ten million dollar bounty on information leading to the disruption of Al-Shabaab’s financial mechanisms.

Kenya’s Coast has long been understood as a region vulnerable to Al-Shabaab influence. In late 2024, an Interpol and AFRIPOL joint operation across eight East African countries resulted in the arrest of 37 terror suspects, including 17 in Kenya alone. Some of those arrested were connected to terrorism financing and propaganda networks.

The question that the prosecution has not yet fully answered in open court is precisely how Elsek’s business empire, if at all, connects to these networks. The charge sheet alleges membership of Al-Shabaab but provides no specific date or location for when that membership began or how it was demonstrated. It alleges possession of propaganda material but has not detailed the chain of custody for the phone or the forensic analysis that was conducted on it. Investigators told the court in January that they were still analysing Elsek’s financial records, banking data, and call logs.

The Questions That Remain

The case of Osman Erdinc Elsek sits at the intersection of several uncomfortable truths about how Kenya handles powerful foreigners, how terrorism charges are deployed, and how quickly political altercations can be reframed as matters of national security.

The first question concerns the speed of the escalation. Senior police sources confirmed to reporters in the days after the arrest that the two Turkish nationals were being detained in connection with the altercation with ODM politicians. The terrorism financing investigation, by the State’s own account, arose from intelligence received prior to the arrest. If that intelligence existed before January 12, the question becomes why Elsek was not detained or investigated on that basis before the highway incident brought him into contact with powerful political figures.

The second question concerns the defilement case. In 2019, Elsek was arrested by the DCI, the GSU, and Interpol on charges of sexually abusing three minors at his home. The case was transferred out of Shanzu after the court itself acknowledged that Elsek had close relations with judicial officers at that station and had helped construct the courthouse. The case eventually collapsed after witnesses recanted and the prosecution failed to prove its case. A related charge of witness interference remains pending. No one has been held publicly accountable for the collapse of that prosecution, and no formal inquiry into the circumstances has been reported.

The third question concerns the firearm. A Glock pistol that was seized in 2020 after Elsek shot a teenager is now back in the possession of his associate. The Standard has found no public record of the outcome of the 2020 shooting case. The pistol’s re-emergence raises questions about the integrity of evidence custody and the functioning of Kenya’s firearms licensing and enforcement regime.

The fourth and perhaps most consequential question is whether the terrorism charges will survive judicial scrutiny. The defence has already argued that the first count is fatally defective for failing to specify when and where the alleged membership took place. The prosecution has not disclosed the intelligence that reportedly preceded the arrest. The financial analysis that investigators said they needed time to complete has not been summarised in open court. The magistrate’s ruling on February 3 will be the first significant test of whether the State has built a case or merely assembled allegations.

“At this point, it is not possible to tell what kind of evidence the state has against the respondents.”

Elsek has maintained throughout that he is a victim, not a suspect. He has pointed to his investments, his corporate social responsibility programmes, and his years of residence as proof that he has no reason to flee Kenya and no motive to support terrorism. His lawyers, including prominent advocates George Khaminwa and Cliff Ombeta, have dismissed the terrorism allegations as politically motivated retaliation for the altercation with the governor’s convoy.

The State, for its part, has said nothing publicly beyond what is contained in the charge sheet and the affidavits filed in court. The investigating officer, Hassan Sugal of the ATPU, told the court that credible intelligence was received before the arrest. What that intelligence was, where it came from, and what it contained has not been disclosed.

What is clear is that a Mombasa court is now being asked to decide whether a Turkish businessman who has lived in Kenya for nearly two decades, built parts of its infrastructure, shot a child, and been charged with sexually abusing minors, is also a member of Al-Shabaab. The answer to that question will say as much about the Kenyan State as it will about Osman Erdinc Elsek.

The case is before a Mombasa magistrate’s court. The ruling on the preliminary objection and the question of plea was expected on Tuesday, February 3, 2026. The Standard will continue to follow developments.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy

-

Economy2 weeks ago

Economy2 weeks agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Arts & Culture2 weeks ago

Arts & Culture2 weeks agoWhen Lent and Ramadan Meet: Christians and Muslims Start Their Fasting Season Together

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoKPC IPO Set To Flop Ahead Of Deadline, Here’s The Experts’ Take

-

Politics2 weeks ago

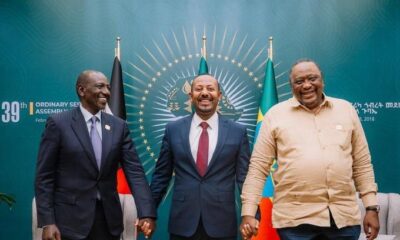

Politics2 weeks agoPresident Ruto and Uhuru Reportedly Gets In A Heated Argument In A Closed-Door Meeting With Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed