Business

Safaricom Sells You Out! Shock Admission: Police Got Your Private Data From Us

This admission could catalyze class-action lawsuits and increased international scrutiny, potentially forcing a broader reckoning over privacy rights and state surveillance in Kenya.

Safaricom Officer Admits Releasing Private Data Without Court Order, Exposing State Surveillance Links

September 9, 2025 — Nairobi, Kenya

A Safaricom officer’s courtroom admission that the telecom giant released sensitive personal data to police without a court order has reignited concerns over the company’s role in Kenya’s surveillance apparatus and alleged connection to enforced disappearances.

The revelation came during the trial of David Oaga Mokaya, a 24-year-old university student charged with publishing false information after posting an AI-generated image of President William Ruto’s coffin on social media platform X.

During cross-examination at Milimani Law Courts on September 8, Safaricom employee Daniel Ndeti confirmed under oath that his company provided call data records, triangulation data, and location tracking information for Mokaya’s phone based solely on a police request letter—without obtaining a court warrant.

“The order was not there,” Ndeti testified when pressed by defense lawyer Danstan Omari about whether proper legal authorization had been secured. The admission directly contradicts a 2018 High Court ruling in *Okiya Omtatah vs. Communications Authority*, which requires court orders for such data releases to protect constitutional privacy rights.

The November 14, 2024 police letter requested comprehensive data including IMEI history, subscriber details, call records from September 15 to November 13, 2024, and geographical locations—information that led to Mokaya’s arrest on November 13.

When Omari challenged Ndeti on the legality of the action, asking “Are you aware that without an existing court order, you’ve violated the accused person’s rights and broken the law?” the Safaricom officer responded defensively: “I’ve not broken any laws because there was a formal request.” Viral video footage captures Ndeti appearing visibly uncomfortable during the exchange, at one point holding his head in his hands.

Mokaya’s prosecution stems from a social media post that allegedly caused public panic, though a DCI data analyst later testified there was no direct evidence linking him to the image, relying instead on IP addresses and device data.

Defense lawyers challenged the prosecution to prove any actual public distress, with a DCI officer admitting he could not confirm that panic had occurred. The case highlights how digital evidence—often obtained through legally questionable means—is being weaponized against critics of the Ruto administration.

This admission is not an isolated incident but part of a documented pattern of allegations against Safaricom, Kenya’s dominant telecom provider with over 40 million subscribers and a 35% government stake.

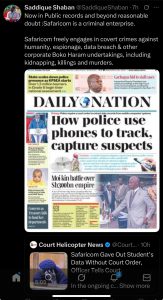

A months-long investigation by Nation Media Group revealed that Safaricom’s systems, modified in 2012 by British firm Neural Technologies, include backdoor access allowing security agencies “virtually unfettered access” to real-time call data and location tracking without warrants.

Police reportedly use triangulation technology to pinpoint locations via mobile phone towers and employ predictive tools to map movements and associations, enabling what sources described as “kill or capture” operations. The surveillance capabilities have allegedly been used in several high-profile disappearances that raise serious questions about state accountability.

Trevor Ndwiga Nyaga’s 2021 disappearance illustrates these concerns. Call data records submitted by Safaricom showed geographical inconsistencies, with one set placing the terrorism suspect near the Somali border and another in Nairobi—suggesting potential data manipulation to obscure foul play. Nyaga was later found dead. Similarly troubling is the case of South Sudanese activists Samuel Dong Luk and Idri Aggrey, who were abducted in Nairobi in 2017. Their call records contained what a UN Panel of Experts deemed fabricated entries, with the panel concluding their subsequent executions were “highly probable.”

The surveillance system’s role became particularly controversial during the 2024 Gen Z protests against government economic policies, which resulted in over 60 deaths and dozens of abductions. Opposition leaders accused Safaricom of aiding police operations by sharing data, prompting public calls for boycotts. One Recce squad officer described how Safaricom’s system can signal when operatives are within 10 meters of targets, facilitating nighttime raids.

Human rights organizations have documented over 80 abductions since mid-2024, many targeting vocal government critics including cartoonist Gideon Kibet and activist Billy Mwangi, both of whom had shared satirical images of President Ruto. The Kenya Human Rights Commission accused Safaricom in an open letter of systematically failing to provide vital data in state crime investigations while readily complying with police requests.

International human rights groups have taken notice. Access Now has urged Vodacom—Safaricom’s parent company—to investigate, citing risks of torture and enforced disappearances. “This erodes trust in digital infrastructure and enables authoritarian control,” said Natalia Krapiva of Access Now.

The courtroom testimony sparked fierce backlash on social media platform X, with users calling for Safaricom boycotts and legal action. Many expressed plans to abandon their Safaricom services, while others suggested the case could lead to successful lawsuits against the company.

Safaricom has consistently denied wrongdoing. CEO Peter Ndegwa stated in May 2025: “Safaricom was not behind GenZ abductions,” insisting that data is shared only with proper court orders. Following the Nation Media Group exposé, the company reiterated that it takes “data protection seriously,” though it faced additional criticism from Reporters Without Borders after allegedly attempting to intimidate the news outlet.

Government officials have largely dismissed the abduction allegations, with Majority Leader Kimani Ichungwah claiming some incidents were “staged” while denying state involvement. This official response has done little to quell growing public concern about the intersection of corporate cooperation and state surveillance.

With Safaricom maintaining a virtual monopoly on Kenya’s telecommunications market and significant government ownership, calls are growing for regulatory reforms, including stricter oversight under the Data Protection Act.

As Mokaya’s trial continues, this admission could catalyze class-action lawsuits and increased international scrutiny, potentially forcing a broader reckoning over privacy rights and state surveillance in Kenya.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoRussian Man’s Secret Sex Recordings Ignite Fury as Questions Mount Over Consent and Easy Pick-Ups in Nairobi

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy

-

Economy1 week ago

Economy1 week agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Africa1 week ago

Africa1 week agoFBI Investigates Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s Husband’s Sh3.8 Billion Businesses in Kenya, Somalia and Dubai

-

Grapevine3 days ago

Grapevine3 days agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoSifuna, Babu Owino Are Uhuru’s Project, Orengo Is Opportunist, Inconsequential in Kenyan Politics, Miguna Says