Opinion

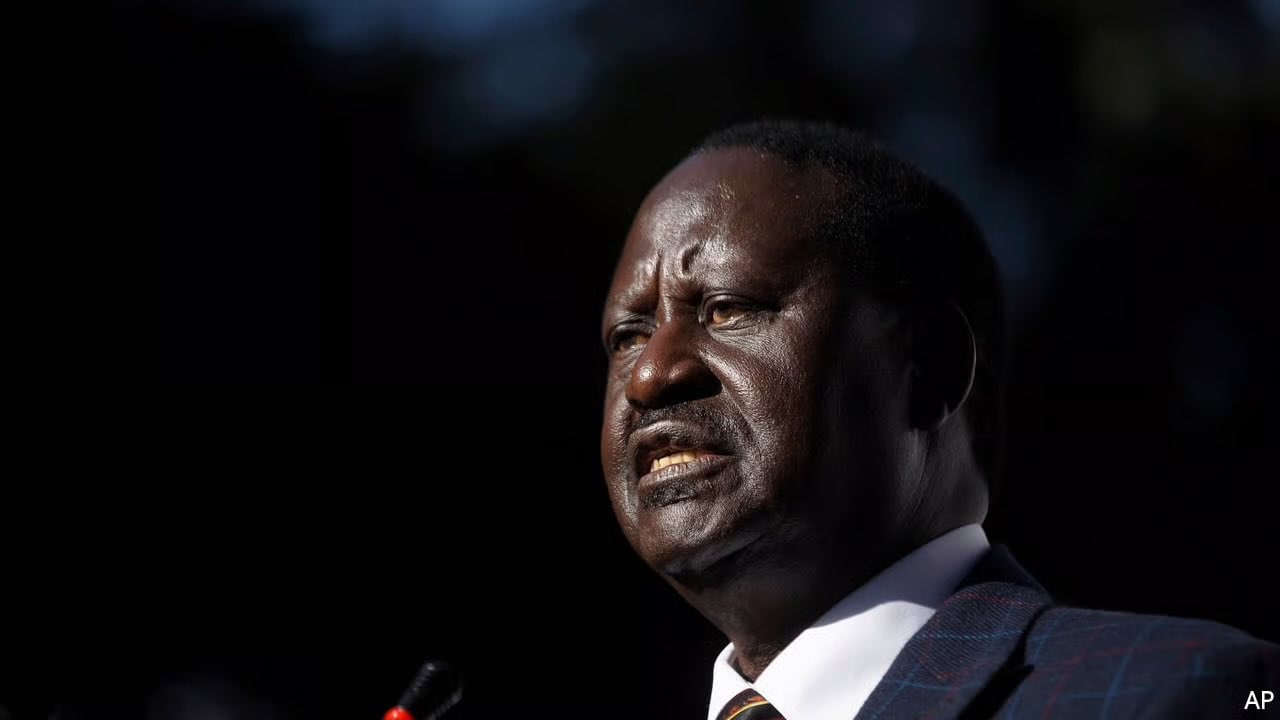

Raila: The Man Presidents Feared To Arrest and The Necessary ‘Devil’ They Needed

Every president from Moi to Ruto discovered that jailing him risked explosion, while accommodating him bought stability.

There exists in the annals of Kenyan politics a peculiar phenomenon that historians will puzzle over for generations.

A man who led street demonstrations against every president from Moi to Ruto, who mobilized millions to challenge sitting governments, who declared himself “the People’s President” in open defiance of the state, yet who walked free while lesser dissidents vanished into Nyayo House torture chambers or faced the full weight of treason charges.

Raila Amolo Odinga occupied that impossible space between revolutionary and statesman, between threat and necessity, between the man who must be stopped and the man who cannot be touched.

The paradox was never accidental. It was calculated survival on both sides of the power equation.

When Daniel arap Moi’s security apparatus rounded up the young engineer after the 1982 coup attempt, they threw him into Kamiti Maximum Prison for six years without trial.

Special Branch officer Josiah Kipkurui Rono beat him with table legs, jumped on his genitals, and held loaded pistols to his temple.

But even as Moi’s regime tortured Raila in basement cells, even as they transferred him between Kamiti, Manyani, Naivasha, and Shimo la Tewa, even as they denied him the chance to bury his mother in 1984, they never quite destroyed him.

And when Moi finally released him in 1988, only to re-arrest him months later, then release him again in 1989, then detain him once more in 1990, a pattern emerged.

The regime could imprison Raila, but it could not make him disappear.

By the time multiparty democracy arrived in 1991 and Raila returned from exile in Norway, something fundamental had shifted.

He was no longer just Jaramogi’s son. He had become a symbol, and symbols cannot be arrested without consequences.

When Raila merged his National Development Party with Moi’s KANU in 2001 and accepted the Energy Ministry, critics screamed betrayal.

How could the man who spent nearly a decade in Moi’s dungeons now sit in Moi’s cabinet? But Moi understood what others missed. Having Raila inside the tent was infinitely preferable to having him outside throwing stones.

The alliance gave Moi’s crumbling KANU parliamentary majority and borrowed legitimacy from a liberation icon. For Raila, it provided proximity to power and influence over constitutional reform. Both men were using each other, each believing they held the upper hand.

The relationship soured when Moi anointed Uhuru Kenyatta as his successor in 2002, bypassing Raila entirely.

The Rainbow Rebellion that followed, with Raila leading disgruntled KANU stalwarts into an alliance with Mwai Kibaki’s opposition, demonstrated the first rule of Kenyan politics that every president would learn: betraying Raila was more dangerous than accommodating him.

The NARC coalition swept to power, ending KANU’s four-decade reign. Kibaki was president, but everyone knew Raila had delivered the votes.

Yet Kibaki repeated Moi’s mistake. He reneged on power-sharing promises, froze Raila out of key decisions, and by 2005 had sacked him from the cabinet altogether.

The country watched as the alliance of convenience disintegrated into bitter rivalry. What followed was the 2007 election, the bloodiest chapter in Kenya’s modern history.

When electoral results showed Kibaki winning by a razor-thin margin that international observers called fraudulent, Raila did not storm State House. He took to the streets.

Here was the moment that crystallized why presidents feared arresting Raila.

As violence erupted across the Rift Valley and Nyanza, as Luo and Kalenjin militias targeted Kikuyu communities and Mungiki death squads retaliated with horrific fury, as 1,300 people died and 600,000 fled their homes, the world waited to see what Raila would do.

He could have called for all-out insurrection.

He could have declared a parallel government and plunged Kenya into civil war. His supporters were ready.

The militias were mobilized. International mediators like Kofi Annan understood that Kenya teetered on the precipice not because Raila was violent, but because his word carried such weight that if he blessed chaos, chaos would consume everything.

Kibaki’s government faced an impossible choice. Arresting Raila would have triggered the very conflagration they desperately wanted to avoid.

His detention would have martyred him, transformed street protests into armed rebellion, and likely fractured the state itself.

The Kikuyu elite who surrounded Kibaki understood power dynamics even if they resented them. Raila commanded not just political allegiance but something more dangerous: the ability to make Kenya ungovernable.

So they cut a deal.

The National Accord of February 2008 created a position that had not existed since independence, the office of Prime Minister, specifically for Raila.

It was an admission that Kenya needed him in government more than it needed him in jail.

The Grand Coalition that followed was dysfunctional, marked by constant friction between the President’s side and the Prime Minister’s side, but it achieved what mattered most. It stopped the killing.

For five years, Raila and Kibaki performed an awkward dance of shared power. Kibaki’s people blocked Raila’s corruption investigations. Raila’s people accused Kibaki’s allies of marginalization.

The famous “Nusu Mkeka” (half-loaf) complaint at a Mombasa retreat captured Raila’s frustration at being a Prime Minister with authority on paper but limited power in practice.

Yet this arrangement delivered Kenya’s most progressive achievement: the 2010 Constitution. Raila championed devolution, fought for stronger checks on executive power, and pushed for an independent judiciary.

The constitution passed overwhelmingly in a referendum, cementing his legacy as more than a political operator. He had fundamentally restructured the Kenyan state.

When Raila lost to Uhuru Kenyatta in 2013 and accepted the Supreme Court’s ruling, observers praised his statesmanship.

But it was strategic pragmatism.

He had secured constitutional reforms that weakened the presidency and empowered counties. The long game mattered more than one election.

The 2017 contest tested that pragmatism.

When Raila again challenged Uhuru’s victory and the Supreme Court delivered an unprecedented ruling, annulling a presidential election for the first time in African history, it vindicated his claims of electoral manipulation.

But Uhuru’s response revealed why presidents needed Raila contained, not imprisoned.

Rather than jail the man who had thrown Kenya into turmoil with his refusal to accept defeat, Uhuru boycotted meaningful electoral reforms and pushed through a repeat election that Raila boycotted.

Raila’s supporters urged him to light the country ablaze. Instead, he staged a mock swearing-in ceremony at Uhuru Park, declaring himself “the People’s President.” It was theater, but theater with teeth.

The regime arrested his lawyer Miguna Miguna and deported him, yet left Raila untouched. Why? Because arresting him would have transformed symbolic defiance into real insurrection.

Uhuru’s security advisors understood that seventy-two-year-old Raila outside prison was less dangerous than martyred Raila behind bars.

Then came the Handshake of March 2018, the most controversial moment of Raila’s career.

Walking up the steps of Harambee House to clasp hands with the man who had “stolen” his presidency shocked supporters and delighted critics who called it the ultimate sellout.

But it followed the established pattern.

Uhuru needed Raila more than he needed him in opposition. The Building Bridges Initiative that emerged promised constitutional reforms, though courts would later strike it down.

What BBI achieved regardless was political stability. It neutered opposition protests and gave Uhuru breathing room to govern.

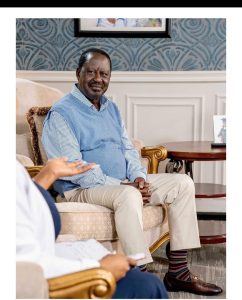

Hundreds of people gather on the streets to bid farewell to former Prime Minister and politician Raila Odinga, who passed away while receiving treatment at a hospital, on October 16, 2025, in Nairobi, Kenya.

Photo credit: REUTERS

For Raila, the Handshake delivered something presidents always underestimated his capacity to value: influence without office. Uhuru’s government stopped treating ODM as the enemy.

Key allies got government appointments. Resources flowed to Raila’s strongholds. And when 2022 arrived, Uhuru backed Raila against his own deputy William Ruto, providing state machinery for the campaign.

That Raila lost to Ruto should have ended the pattern.

At seventy-seven years old, after five unsuccessful presidential bids, the narrative should have concluded with the aging revolutionary finally defeated.

Instead, by March 2025, Raila was negotiating yet another deal, this time with the man who had defeated him.

When Gen Z protests threatened to topple Ruto’s government over punitive taxation, when young Kenyans filled the streets demanding accountability, Raila emerged as the mediator.

The “broad-based government” agreement that placed ODM officials in Ruto’s cabinet shocked the youth who expected him to lead the revolution they were waging.

But it exemplified the fundamental truth about why presidents never arrested Raila.

He was simultaneously the match that could ignite Kenya and the fire extinguisher that could douse the flames.

Every president from Moi to Ruto discovered that jailing him risked explosion, while accommodating him bought stability.

The calculation was never about justice or democracy or institutional integrity. It was about power and pragmatism.

Arresting Raila meant facing the wrath of millions who saw him as the living embodiment of their democratic aspirations.

It meant international condemnation and potential sanctions. It meant protests that could escalate beyond police control. Most crucially, it meant losing access to the one man who could call off the dogs when the streets became too hot.

Presidents feared arresting Raila not because he was violent, but because his power transcended violence. He could mobilize masses, yes, but more importantly, he could demobilize them.

That dual capacity made him indispensable.

In 2008, Kofi Annan brokered peace not by convincing Kibaki to share power, but by convincing Raila to accept half a loaf rather than burn down the bakery.

In 2018, Western diplomats and African Union envoys facilitated the Handshake because they knew that only Raila could end the cycle of contested elections and ethnic violence.

In 2025, Ruto needed Raila to pacify Gen Z and legitimize his embattled government.

The pattern reveals a darker truth about Kenyan democracy.

The system has never trusted its own institutions to mediate political conflict. Courts could annul elections, but only Raila could prevent civil war.

Parliament could pass laws, but only Raila could determine whether the streets would accept them. Electoral commissions could count votes, but only Raila’s word determined whether those counts would stand unchallenged by millions ready to march.

This made him the necessary devil every president needed. Moi needed him to shore up KANU’s legitimacy.

Kibaki needed him to end post-election violence. Uhuru needed him to stop opposition protests and maintain political stability. Ruto needed him to survive Gen Z fury and create the appearance of a broad-based government. Each time, the price was accommodation rather than incarceration.

Critics will argue that Raila squandered his liberation credentials through these devil’s bargains, that he betrayed supporters who expected him to storm State House or die trying. Gen Z demonstrators certainly believed so, rejecting his mediation as old-guard complicity.

But this critique misunderstands both Raila’s strategic genius and Kenya’s political reality. He recognized that the presidency itself mattered less than shaping the terrain on which all presidents must operate.

The 2010 Constitution, devolution, an independent judiciary, and the normalization of political competition were his true achievements. Each president he negotiated with conceded ground, ceded space, and weakened the imperial presidency.

That he never captured State House obscures the fact that he fundamentally altered what State House could do. Moi’s autocracy became impossible under the 2010 Constitution Raila championed.

Kibaki’s ability to rig elections faced new constraints.

Uhuru’s power-sharing with Raila prevented the authoritarian regression that consumed many African states. Ruto’s embattled presidency must accommodate opposition in ways unthinkable during the KANU era.

The fear of arresting Raila was ultimately fear of what he represented: an alternative locus of power that the state could suppress temporarily but never eliminate permanently.

Detention could remove him from the streets for months or years, but it could not erase his symbolic authority.

His father Jaramogi had been Kenya’s first vice president before Jomo Kenyatta betrayed and sidelined him, creating a narrative of Luo exclusion from power that resonated across generations. Raila inherited that narrative and weaponized it.

Every detention, every rigged election, every marginalization only strengthened the story: the Odingas represented democracy against dictatorship, popular will against elite capture, the people against the system.

Arresting him would have confirmed that narrative and martyred him.

Accommodating him co-opted his legitimacy for the sitting government while giving him influence to shape outcomes.

Presidents chose the lesser evil every time.

When Raila Odinga collapsed during a morning walk in Kerala, India, on October 15, 2025, and died of a heart attack, Kenya lost the man who had defined its political culture for half a century.

From Kamiti’s torture chambers to the Prime Minister’s office, from exile in Norway to handshakes at Harambee House, from mock swearing-in ceremonies to coalition governments, his journey traced the arc of Kenya’s democratic struggle.

He was detained, beaten, rigged against, and betrayed, yet he outlasted four presidents and negotiated with all of them.

The epitaph that matters is not that he never became president, but that he made every president reckon with him.

They feared arresting him because they needed him. They needed him to legitimize their contested victories, to pacify angry populations, to provide democratic cover for authoritarian impulses, to be the bridge between the people and power.

He was the necessary devil who could never be vanquished, only accommodated.

Kenya will produce other opposition leaders, other challengers, other voices of dissent. But it will not soon see another figure who commands such absolute loyalty that presidents dare not jail him even as he leads demonstrations against them.

That was Raila’s singular achievement: he made himself untouchable not through violence or wealth or ethnic chauvinism, but through the sheer force of symbolic power.

He became larger than any prison could contain, more dangerous free than imprisoned, more useful inside government than outside it.

The presidents who feared to arrest him and needed his cooperation understood this truth better than anyone.

Raila Odinga was never just one man. He was an idea, and ideas cannot be detained without creating martyrs.

Better to negotiate with the devil you know than to create a legend you cannot control. Every Kenyan president learned that lesson, some more painfully than others.

The streets belonged to Raila, even when State House did not. And in Kenya’s messy, violent, inspiring democratic experiment, that mattered more than any title.

Supporters of Former Prime Minister Raila Odinga viewing his body at Kasarani Stadium in Nairobi on October 16,2025.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoAlleged Male Lover Claims His Life Is in Danger, Leaks Screenshots and Private Videos Linking SportPesa CEO Ronald Karauri

-

Lifestyle2 weeks ago

Lifestyle2 weeks agoThe General’s Fall: From Barracks To Bankruptcy As Illness Ravages Karangi’s Memory And Empire

-

Grapevine5 days ago

Grapevine5 days agoRussian Man’s Secret Sex Recordings Ignite Fury as Questions Mount Over Consent and Easy Pick-Ups in Nairobi

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoEpstein Files: Sultan bin Sulayem Bragged on His Closeness to President Uhuru Then His Firm DP World Controversially Won Port Construction in Kenya, Tanzania

-

Investigations2 days ago

Investigations2 days agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoEpstein’s Girlfriend Ghislaine Maxwell Frequently Visited Kenya As Files Reveal Local Secret Links With The Underage Sex Trafficking Ring

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoState Agency Exposes Five Top Names Linked To Poor Building Approvals In Nairobi, Recommends Dismissal After City Hall Probe

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoM-Gas Pursues Carbon Credit Billions as Koko Networks Wreckage Exposes Market’s Dark Underbelly