Investigations

Mishra Invokes God’s Name Claiming Innocence Despite Overwhelming Evidence Linking Him to Organ Trafficking

While other hospitals charged an average of Sh990,743 per procedure, Mediheal’s mean bill was Sh2,313,324—a staggering 133 percent premium that investigators say “suggests potential billing irregularities.”

Mediheal Hospital chairman’s emotional denial comes as government investigators detail systematic exploitation of vulnerable donors

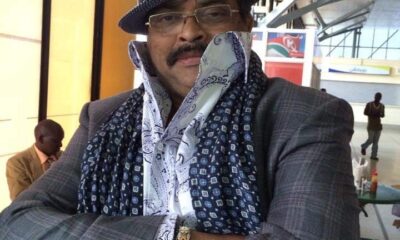

Dr. Swarup Mishra, the embattled chairman of Mediheal Group of Hospitals, made a desperate appeal to divine authority yesterday as mounting evidence of systematic organ trafficking at his facility threatens to unravel what investigators describe as a sophisticated international operation targeting Kenya’s most vulnerable populations.

“In the name of God, I am innocent,” declared a tearful Mishra during a press conference in Nairobi, his voice breaking as he faced recommendations from an 18-member government task force that he be criminally investigated for organ trafficking violations. “If anyone has evidence of organ trafficking at Mediheal, let them come forward.”

But the evidence appears overwhelming. A damning government investigation has exposed what prosecutors are calling a carefully orchestrated system that exploited poor Kenyans and Central Asian nationals to supply kidneys for wealthy foreign recipients, particularly from Israel, while generating millions of shillings in profits.

The numbers don’t lie

The scale of operations at Mediheal dwarfs all other transplant facilities in Kenya.

Between 2018 and March 2025, the Eldoret-based hospital performed 476 kidney transplants accounting for approximately 81 percent of all donors and 76 percent of recipients across the 33 hospitals investigated nationwide.

More disturbing are the payment patterns uncovered by investigators.

While other hospitals charged an average of Sh990,743 per procedure, Mediheal’s mean bill was Sh2,313,324—a staggering 133 percent premium that investigators say “suggests potential billing irregularities.”

The hospital operated a three-tier pricing structure that investigators found deeply troubling: Kenyans paid Sh2 million, African patients $25,000, and international patients from outside Africa $34,000. Most concerning, 347 patients paid cash out-of-pocket, with investigators finding that 25.1 percent of Mediheal donors were “highly likely” to have received cash payments—nearly seven times the rate at other facilities.

The Azerbaijan-Israel pipeline

Perhaps the most damning finding involves what investigators describe as a “systematic pipeline” of organs from Azerbaijan to Israel.

The task force expressed “grave concern” that 25 donors specifically for Israeli recipients came from Azerbaijan—a pattern so unusual it raised immediate suspicions of patient misidentification, forged documents, or “targeted recruitment.”

The gender imbalances paint an even darker picture. Among Azerbaijani participants, investigators found 43 male donors versus only seven females, while Israeli recipients showed 50 males compared to just eight females.

Combined with the virtual absence of Israeli donors, this suggests a system where Israeli men systematically benefit from organs harvested from vulnerable Azerbaijani males.

“This pattern indicates that Azeri men are being systematically recruited as organ donors for transplantation elsewhere,” the investigation concluded, recommending immediate involvement of security agencies.

Regulatory failures and systemic weaknesses

The investigation revealed shocking regulatory failures that enabled the alleged trafficking to flourish.

Staff licenses had expired, key personnel were missing, and the facility lacked essential safeguards including multidisciplinary committee meetings and patient advocates.

Most concerning, consent forms for donors and recipients were not translated into languages they could understand, laboratory samples were sent to unregistered facilities in India, and there was no long-term follow-up care for patients.

Dr. A.S. Murthy, the nephrologist responsible for patient care, described his operation as a “one-man show” conducting counselling for both donors and recipients himself, creating obvious conflicts of interest. The same doctor had never joined the Kenya Renal Association despite eight years of practice in the country.

Marketing the human body

The investigation uncovered a sophisticated marketing operation that used social media to recruit donors and arrange accommodation through commercial platforms.

A former employee revealed she worked as a marketing coordinator from 2018 to 2023, specifically targeting nephrologists and renal nurses for patient referrals while coordinating the arrival of foreign patients, especially from Israel.

Videos supposedly showing donor consent appeared similar to marketing materials promoting services to international kidney recipients, raising questions about whether genuine informed consent was ever obtained.

A pattern of denial

Despite the overwhelming evidence, Mishra and his legal team have launched a counteroffensive, claiming they are victims of a “fault-finding, not fact-finding” mission.

His lawyers argue that the hospital fully cooperated by providing 60,000 pages of documents and maintaining that investigators found “no single incident of organ trafficking.”

But this defense rings hollow against the backdrop of systematic irregularities documented by investigators.

The hospital’s own data shows 15 patients died during procedures, with complications including renal artery thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Yet Mediheal conducted no post-transplant audits for morbidity and mortality.

Beyond one hospital

The Mediheal case represents more than isolated criminal activity—it exposes fundamental weaknesses in Kenya’s healthcare regulatory system that allowed systematic exploitation to flourish for years.

The investigation recommends criminal probes not only of Mediheal staff but also of officials at the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council for “regulatory failure and possible collusion.”

As Mishra invokes divine protection while 2,300 employees lose their jobs due to the scandal, the victims of this alleged trafficking network—poor Kenyans and vulnerable Central Asians who may have sold their organs for survival—remain largely invisible in the public discourse.

The task force has given investigators until July 22 to submit final findings.

But for families who may have lost loved ones to organ harvesting, and donors who may have been exploited in their desperation, divine justice may prove more elusive than Mishra hopes.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoAlleged Male Lover Claims His Life Is in Danger, Leaks Screenshots and Private Videos Linking SportPesa CEO Ronald Karauri

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoRussian Man’s Secret Sex Recordings Ignite Fury as Questions Mount Over Consent and Easy Pick-Ups in Nairobi

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Investigations7 days ago

Investigations7 days agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy

-

Economy6 days ago

Economy6 days agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Africa1 week ago

Africa1 week agoFBI Investigates Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s Husband’s Sh3.8 Billion Businesses in Kenya, Somalia and Dubai

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoM-Gas Pursues Carbon Credit Billions as Koko Networks Wreckage Exposes Market’s Dark Underbelly