Politics

Matiang’i Isolated: Behind The Scenes Rivalry in Opposition Inner Circle Erupts in Public

Gachagua slams Matiang’i over campaign strategy: There is no president you’ll make in the boardroom. Presidents are made in the field.

Former Interior CS finds himself increasingly sidelined as Gachagua’s aggressive tactics threaten to splinter opposition unity ahead of 2027 polls

The veneer of unity within Kenya’s opposition has spectacularly crumbled, exposing a toxic cocktail of ego, ethnicity and naked ambition that threatens to hand President William Ruto an easy path to re-election in 2027.

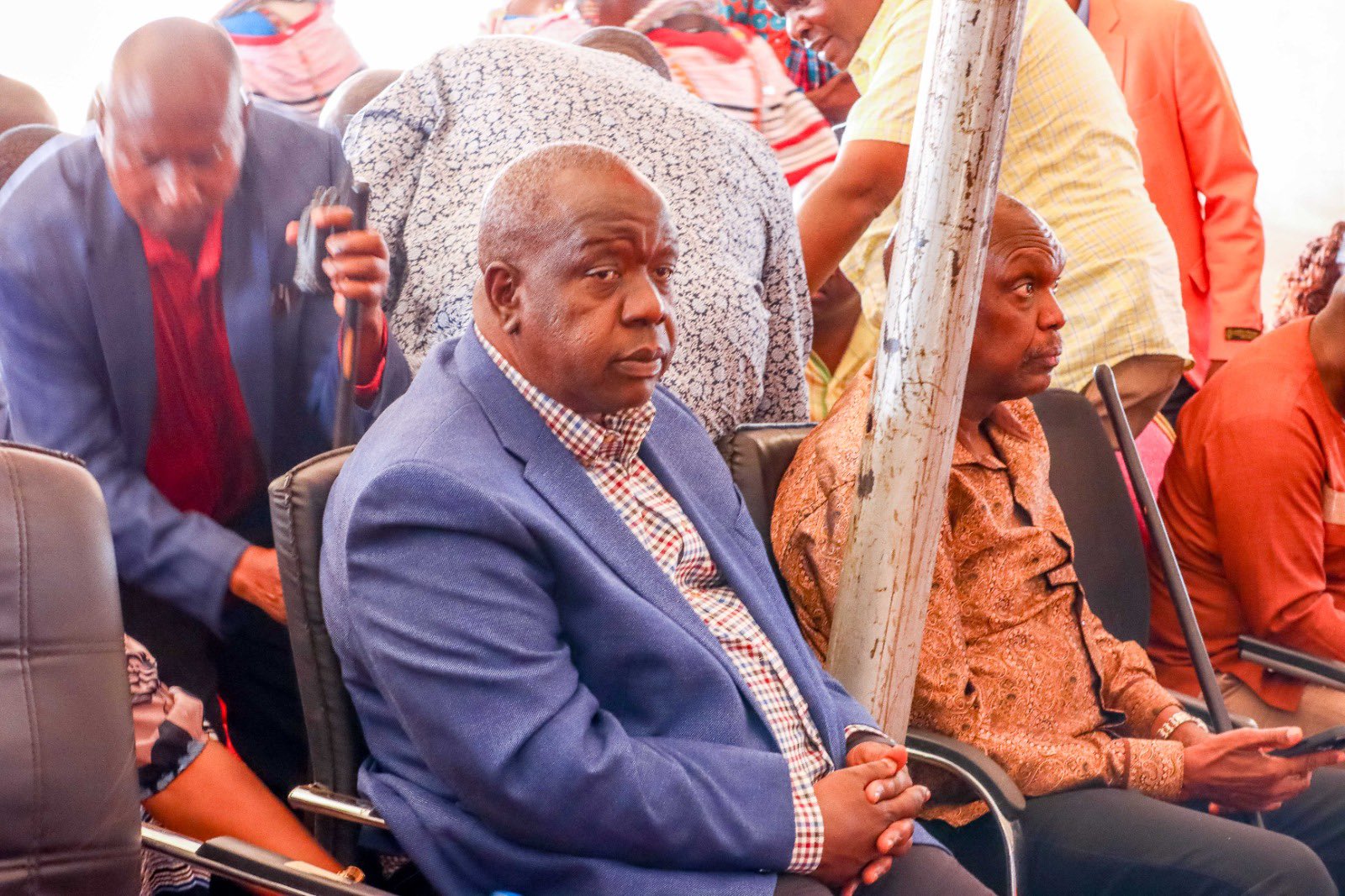

At the centre of this implosion is former Interior Cabinet Secretary Fred Matiang’i, who finds himself fighting a lonely battle against former Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua’s increasingly aggressive attempts to dominate the opposition space .

What was supposed to be a formidable coalition to unseat Ruto has instead become a stage for petty squabbles, with Gachagua positioning himself as the undisputed kingmaker while systematically isolating anyone who dares challenge his supremacy.

The public spat between the two men on Friday laid bare the deep fissures running through the United Opposition.

While his colleagues were courting voters in Kajiado, Matiang’i was conspicuously absent, holding his own rally in Nakuru in what insiders say was a deliberate snub to Gachagua’s increasingly dictatorial style.

The message was clear: Matiang’i will not be bullied into abandoning his Jubilee Party base to genuflect before Gachagua’s Democracy for Citizens Party.

Gachagua’s remarks at the DCP headquarters dripped with contempt for his ostensible ally.

His dismissive reference to “boardroom negotiations” and social media posturing was a thinly-veiled attack on Matiang’i’s approach to politics. But it was his ethnic dog whistle telling Matiang’i to “go get a party solidifying his base in Kisii region” that revealed the true nature of his game.

Gachagua is not interested in building a national coalition. He wants to carve up Kenya into ethnic fiefdoms, with himself controlling the lucrative Mount Kenya vote bank.

This Balkanisation strategy is precisely what has kept Kenya’s opposition perpetually weak. Instead of building a movement based on ideology and national interest, Gachagua is resurrecting the tired ethnic arithmetic that has failed Kenya for decades.

His boast, as revealed by Jubilee Secretary-General Jeremiah Kioni, of controlling “seven million votes from the mountain, one million from Kalonzo, and 800,000 from Matiang’i” exposes a man who sees his allies not as partners but as vote contractors subservient to his grand design.

Matiang’i’s defiance in Nakuru was therefore not just about defending his choice to remain in Jubilee. It was a principled stand against the ethnic balkanisation of Kenyan politics.

His insistence that “you cannot choose a party for someone” and his call for democracy within the opposition alliance represents a fundamentally different vision from Gachagua’s strongman approach.

But principle alone does not win elections in Kenya, and Matiang’i’s isolation within the coalition suggests he is losing this battle.

The former Interior CS finds himself in an impossible position. His association with former President Uhuru Kenyatta’s Jubilee Party is both his strength and his Achilles heel.

While it gives him institutional support and a ready-made party structure, it also makes him vulnerable to accusations of being Uhuru’s “lapdog” and a Trojan horse for the old establishment.

Critics like lawyer Ndegwa Njiru have openly dismissed him as “a political novice” who could be used to split opposition votes , further undermining his credibility within the coalition.

Gachagua, by contrast, has successfully positioned himself as the anti-establishment rebel, the victim of state persecution who was impeached for standing with the common man.

Never mind that his own record as Deputy President was marked by the same ethnic mobilisation and political opportunism he now deploys against Ruto.

His persecution narrative has given him a legitimacy that Matiang’i, who served in both Uhuru’s and briefly in Ruto’s government, struggles to match.

The accusation by Kioni that Gachagua has been cutting deals with Ruto in Narok adds another layer of intrigue to this mess.

While Gachagua has vehemently denied any betrayal, the allegation speaks to a deeper suspicion within the opposition: that he is more interested in using the coalition as leverage to negotiate his way back to relevance rather than genuinely committing to regime change.

His aggressive domination of the opposition space, his insistence that DCP be the sole vehicle for Mount Kenya, and his systematic sidelining of rivals like Matiang’i all point to a man playing a longer, more cynical game.

For Matiang’i, the options are increasingly bleak. He can continue to fight from within, defending his Jubilee base while hoping that his patience and principle will eventually be rewarded.

But this strategy requires that the opposition actually wins in 2027, a prospect that looks increasingly remote given the current dysfunction.

Alternatively, he could break away entirely, but that would simply accelerate the fragmentation of the opposition and guarantee Ruto’s re-election.

The real winners in this spectacle are President Ruto and his Kenya Kwanza coalition.

Every public spat between opposition leaders reinforces Ruto’s image as the only politician with organisational discipline. Every accusation and counter-accusation proves that the opposition is not ready to govern.

The chaos within the United Opposition is a gift that keeps on giving to a President who faces serious challenges on multiple fronts but can at least count on his enemies to destroy themselves.

Political analysts have warned that this disarray is precisely what Ruto needs to cement his political base.

While the opposition burns through its political capital in internal wars, Ruto’s team is busy consolidating support, deploying technocrats to counter Gachagua’s influence, and building a national machinery that will be nearly impossible to defeat if the opposition cannot get its act together.

The tragedy is that Kenya desperately needs a viable opposition. Ruto’s government has presided over economic hardship, allegations of extrajudicial killings, and massive corruption.

There is genuine public appetite for change.

But that change requires a united front, a coherent alternative vision, and leaders willing to subordinate their egos to a larger cause. None of these elements are currently visible in the opposition.

Gachagua’s bulldozing tactics, his ethnic mobilisation strategy, and his apparent inability to work with anyone who does not submit to his authority are not signs of strong leadership.

They are the marks of a politician who learned nothing from his own impeachment, who believes that might makes right, and who is willing to sacrifice the opposition’s chances of victory on the altar of his own ambition.

Matiang’i’s isolation is therefore not just about one man’s struggle for relevance. It is a symptom of a broader disease afflicting Kenya’s opposition: the inability to build coalitions based on shared purpose rather than ethnic arithmetic, the preference for strongman politics over democratic deliberation, and the triumph of personal ambition over national interest.

Unless something changes dramatically, the 2027 election is already decided.

Not because Ruto is unbeatable, but because the opposition has beaten itself. And Kenyans, who deserve better than this circus, will once again be asked to choose between an unpopular incumbent and a dysfunctional alternative that cannot even agree on who should carry their flag, let alone what they stand for.

The next two years will determine whether the opposition can salvage something from this wreckage. But based on current evidence, Gachagua’s aggressive dominance and Matiang’i’s isolation suggest that the United Opposition is neither united nor much of an opposition.

It is simply a collection of wounded egos, ethnic entrepreneurs, and political opportunists playing out their personal dramas on the national stage while Ruto watches and smiles.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoJulius Mwale Throws Contractor Under the Bus in Court Amid Mounting Pressure From Indebted Partners

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoEastleigh Businessman Accused of Sh296 Million Theft, Money Laundering Scandal

-

Investigations5 days ago

Investigations5 days agoInside Nairobi Firm Used To Launder Millions From Minnesota Sh39 Billion Fraud

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoMost Safaricom Customers Feel They’re Being Conned By Their Billing System

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoEXPLOSIVE: BBS Mall Owner Wants Gachagua Reprimanded After Linking Him To Money Laundering, Minnesota Fraud

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoUnfit for Office: The Damning Case Against NCA Boss Maurice Akech as Bodies Pile Up

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoTax Payers Could Lose Millions in KWS Sh710 Insurance Tender Scam As Rot in The Agency Gets Exposed Further

-

Americas2 weeks ago

Americas2 weeks agoUS Govt Audits Cases Of Somali US Citizens For Potential Denaturalization