News

EXPOSED: How Tycoon Munga, State Officials, Chinese Firm Stalled A Sh3.9 Trillion Coal Treasure In Kitui

The real victims in this saga are the people of Kitui County, who have watched for over a decade as politicians and tycoons played games with their future.

In the dusty, sun-scorched expanse of Mui Basin in Kitui County lies a fortune so vast it could transform Kenya’s economic trajectory forever. Four hundred million tonnes of coal, conservatively valued at Sh3.9 trillion, sits buried beneath the earth, untouched, unexploited, and caught in a web of greed, bureaucratic sabotage, and raw power politics that has paralyzed the project for over a decade.

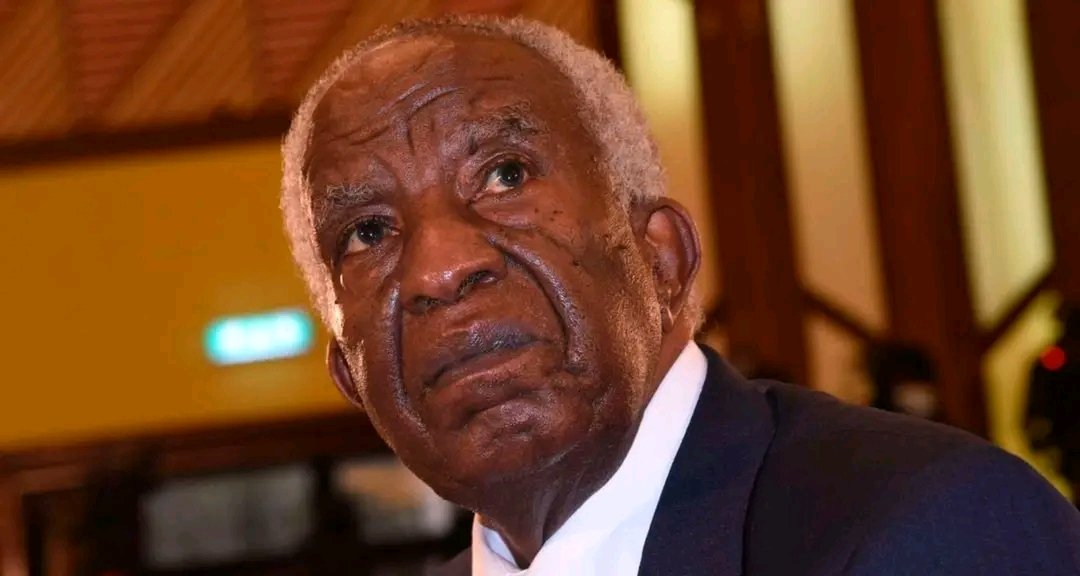

The story of the Mui Basin coal mining project is a tale of how one of Kenya’s most celebrated business tycoons, Peter Munga, the revered founder of Equity Bank, allegedly joined hands with shadowy government mandarins to frustrate a Chinese mining firm that legitimately won the tender to extract this black gold. It is a story of broken promises, unpaid millions, and a nation held hostage by the competing interests of the powerful.

At the heart of this scandal is a simple but damning fact: Great Lakes Corporation Limited, owned by Peter Munga and businessman George Kariithi, failed to honor their commitment to pay their local venture contribution amounting to Sh388 million and were officially dropped from the project in May 2018. Yet, more than seven years later, through alleged collusion with top Ministry of Energy officials, they continue to haunt the project like ghosts who refuse to leave a house they no longer own.

The Chinese mining giant, Fenxi Mining Industry Company Limited, which was awarded the prestigious 21-year concession in September 2011, has watched in frustration as years turned into decades without a single tonne of coal being extracted. In August 2025, their patience finally ran out. FMICL served the Energy and Mining ministries with a notice of default, demanding the necessary consents to begin coal extraction within 60 days or face arbitration proceedings in Mauritius .

The Chinese firm’s allegations are explosive. In correspondence seen by Kenya Insights, FMICL chairman Yang Wu Sheng directly accused government representatives of showing what he termed “a seemingly biased preference” for Great Lakes Corporation, despite the company’s engagement having been formally terminated. The letter, dripping with diplomatic restraint but barely concealing deep anger, painted a picture of systematic obstruction orchestrated from the highest levels of Kenya’s energy bureaucracy.

Peter Munga, now in his eighties, is no ordinary businessman. He is the man who transformed a struggling microfinance institution started with just Sh5,000 in 1984 into Equity Bank, one of Africa’s largest financial institutions serving nearly 20 million customers across six countries . His rags-to-riches story, from a boy who grew up in penury after his father was jailed during the Mau Mau uprising to becoming a billionaire with interests spanning banking, insurance, agriculture, and real estate, has made him a celebrated figure in Kenya’s business pantheon.

But the Mui Basin saga reveals a darker side to this entrepreneurial legend. According to documents obtained by our investigation, Munga and his partner Kariithi entered into a joint venture with FMICL in 2013, forming Fenxi Mui Mining Corporation Limited with a 70-30 shareholding split favoring the Chinese firm. To seal the deal and secure the mining rights, the consortium was required to pay the government $5 million in concession fees. FMICL was to contribute $1.125 million while Great Lakes Corporation was obligated to pay $3.875 million.

The Chinese firm paid their share, but Great Lakes never honored their financial commitment. By May 2018, after years of promises and broken deadlines, FMICL formally terminated the partnership and brought in Dorse Gems International Limited as their new local partner, forming Fenxi Dorse International Power Limited.

In any normal business transaction, this would have been the end of the matter. Great Lakes failed to pay, they were out. But this is Kenya, where political connections and insider dealings can trump legal agreements and Attorney General opinions.

In November 2020, then Attorney-General Paul Kihara Kariuki issued a clear legal opinion to then Energy Cabinet Secretary Charles Keter, stating unequivocally that the concession legally belonged to Fenxi Mining Industry Co. Ltd, which had the exclusive right to carry out the mining works or assign those rights to a subsidiary of its choosing . The AG’s opinion demolished Great Lakes Corporation’s claims that the concession somehow belonged to the consortium rather than the Chinese firm that had actually paid for it.

Yet government officials continued to entertain Munga and Kariithi as if they still had legitimate standing in the project. Ministry of Energy bureaucrats held secret meetings with Great Lakes representatives, creating what FMICL describes as bureaucratic obstacles that prevented them from either commencing mining operations or selling the concession rights to other interested investors.

The motive becomes clearer when you consider what is at stake. Beyond the headline-grabbing Sh3.9 trillion valuation of the coal reserves, the project was expected to generate 960 megawatts of electricity, create thousands of jobs, and catalyze industrial development in one of Kenya’s most marginalized regions. For anyone with a piece of the action, the potential returns would be astronomical.

In 2014, even as their financial obligations remained unpaid, Munga and Kariithi wrote to the Ministry of Energy on the letterhead of Fenxi Mui Mining Corporation Limited, boldly claiming to speak on behalf of the consortium and promising that payment of concession fees would be completed by May 2, 2014. They name-dropped prestigious institutions like Deloitte Beijing, HSBC’s Nairobi and Hong Kong offices, and financiers such as the US Power Africa Fund, creating an impression of serious business dealings. But according to FMICL, not a single shilling was ever paid by Great Lakes Corporation.

The Chinese firm’s frustration is palpable in their August 2024 letter to Chief of Staff Felix Koskei. “Following the execution of the agreement, we have made several efforts to progress with the implementation and operationalisation of the project. However, these initiatives encountered various hurdles,” Yang Wu Sheng wrote, his words carefully chosen but the message unmistakable: they were being deliberately blocked.

The pattern of obstruction continued into 2025. In July, Energy Cabinet Secretary Opiyo Wandayi and then Environment Cabinet Secretary Soipan Tuya publicly stated they were working to halt the project, citing environmental concerns and community protests. Yet in October 2025, during a tour of Kitui ahead of Energy Week, Wandayi made an about-face, announcing that the government was getting the coal mining project back on track. He called it “well overdue” and promised the locals that the project would create employment and unlock the county’s energy potential.

What changed between July and October? Why the sudden reversal? Our sources within the Ministry suggest that the threat of international arbitration finally concentrated minds in government. If Kenya lost the case in Mauritius, the country could be liable for billions in compensation, not to mention the reputational damage to Kenya as an investment destination.

The real victims in this saga are the people of Kitui County, who have watched for over a decade as politicians and tycoons played games with their future. Approximately 100,000 people, more than 30,000 households primarily composed of small-scale farmers, stand to be displaced to make way for the coal mining operations . These communities have been left in limbo, unable to plan for their futures, unsure whether to stay or leave, while the powerful fight over the spoils.

There are also broader questions about Kenya’s energy strategy. Critics point out that Kenya currently has overcapacity in electricity generation and that coal does not compare favorably with other sources such as geothermal power . Environmental activists have warned that pursuing coal mining at a time when the world is phasing out fossil fuels could leave Kenya with stranded assets and saddle the country with expensive, dirty energy.

But these policy debates have been overshadowed by the raw power struggle between FMICL, Great Lakes Corporation, and the government officials who appear to be taking sides. The project has become less about energy security or economic development and more about who gets to control and benefit from billions of shillings worth of mineral wealth.

For Peter Munga, whose public image has been built on his humble beginnings and his commitment to uplifting ordinary Kenyans through initiatives like the Wings to Fly scholarship program, the Mui Basin controversy represents an uncomfortable chapter. When contacted by Kenya Insights, Munga declined to comment on the specifics, saying he was “not well-versed with the day-to-day operations of Great Lakes Corporation” and directing inquiries to his partner George Kariithi. Kariithi did not respond to multiple attempts to reach him.

The Chinese firm, for its part, has made clear that it will not back down. With the 60-day deadline from their August 2025 default notice now expired, FMICL is poised to take Kenya to international arbitration. If they win, and legal experts say their case is strong given the Attorney General’s opinion and Great Lakes’ failure to pay, Kenya could face a compensation bill that dwarfs the value of the concession itself.

As this investigation went to press, the Kenyan government had not yet granted the consents that FMICL has been requesting since 2022 to officially recognize Dorse Gems International as the new local partner. Ministry officials have remained tight-lipped about why a straightforward administrative process has taken three years and counting.

What is clear is that powerful interests within the government continue to protect Great Lakes Corporation’s ghost claim to a project they never paid for. Whether this is due to personal relationships, political considerations, or something more sinister remains a subject of intense speculation in Nairobi’s corridors of power.

The Mui Basin coal mining project was supposed to be a story of Kenya harnessing its natural resources to power industrialization and lift its people out of poverty. Instead, it has become a cautionary tale about how greed, political meddling, and the protection of well-connected insiders can paralyze even the most promising national projects. As Sh3.9 trillion worth of coal continues to sit untouched beneath the earth of Kitui County, one question lingers: How many more years will Kenya allow this scandal to continue?

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Development4 days ago

Development4 days agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoHow Close Ruto Allies Make Billions From Affordable Housing Deals

-

Entertainment2 weeks ago

Entertainment2 weeks agoKRA Comes for Kenyan Prince After He Casually Counted Millions on Camera

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoAmerican Investor Claims He Was Scammed Sh225 Million in 88 Nairobi Real Estate Deal

-

Investigations1 week ago

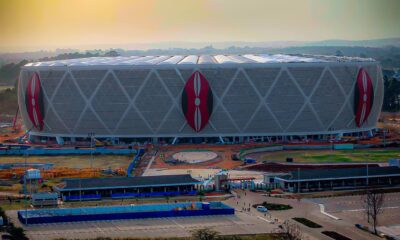

Investigations1 week agoTalanta Stadium Construction Cost Inflated By Sh11 Billion, Audit Reveals