Politics

Defunding Education? Ruto Scraps Uhuru’s Sh5B Exam Waiver

Government shifts to targeted subsidy model as parents face return of examination fees after decade-long waiver

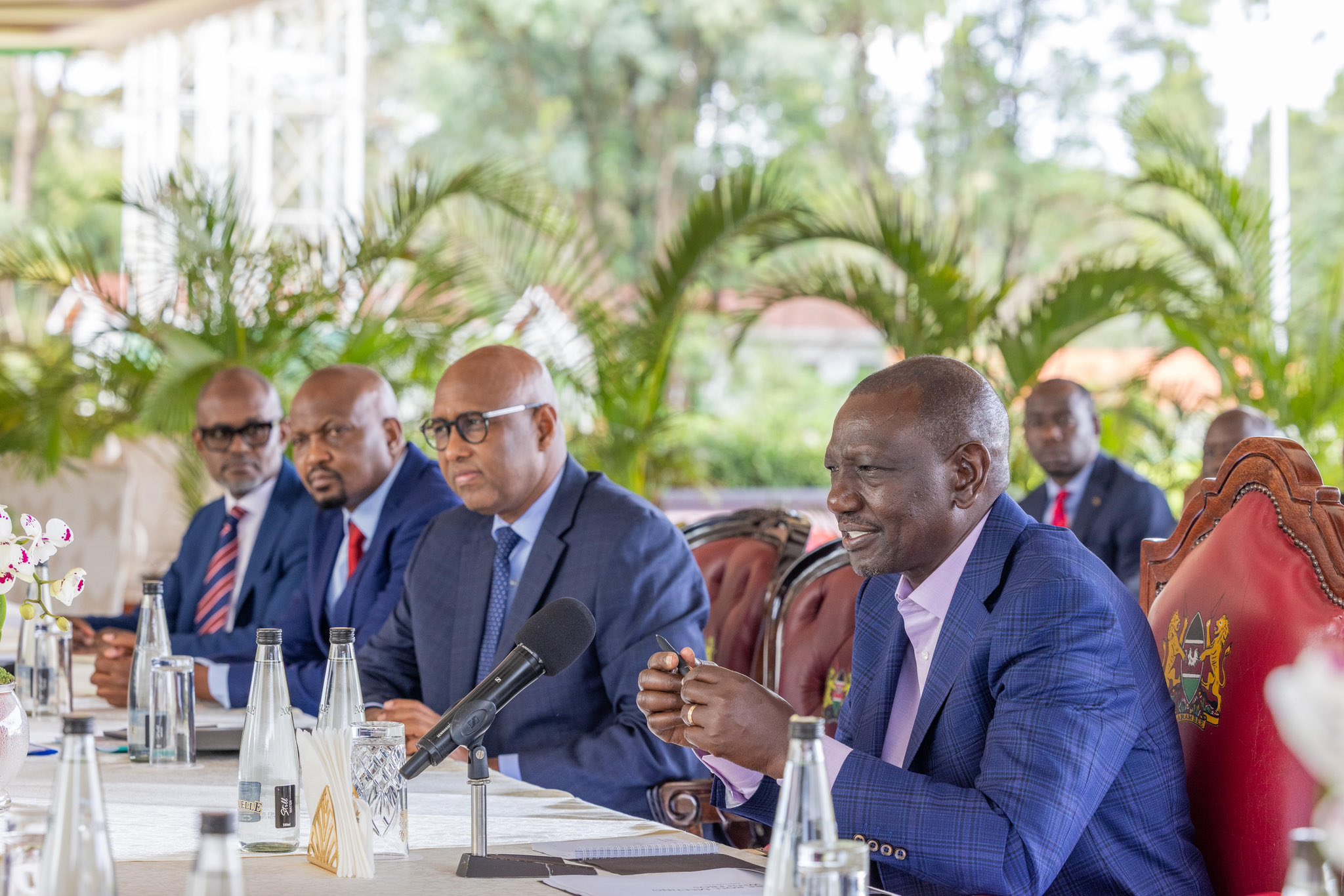

In a dramatic policy reversal that threatens to burden millions of Kenyan families, President William Ruto’s administration has announced plans to scrap the universal examination fee waiver introduced by former President Uhuru Kenyatta in 2015, forcing parents to once again pay for their children’s national examinations starting next year.

Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi revealed the controversial decision in a recent interview, signaling the end of a decade-long policy that has enabled all learners in both public and private schools to sit national examinations without cost.

The move affects the Kenya Primary School Education Assessment (KPSEA), Kenya Junior School Education Assessment (KJSEA), and Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) examinations.

The new policy mirrors the government’s contentious higher education funding model introduced in 2023, shifting from universal coverage to a targeted subsidy approach that will only benefit students deemed “needy” through an undisclosed means-testing mechanism.

“The Ministry of Education must come up with criteria of identifying those who can pay examination fees,” Mbadi explained, defending the policy with pointed rhetoric.

“If your child is learning in a private school where you pay Sh300,000 per term or Sh1 million in a year, honestly, can’t you pay Sh5,000 examination fees for that child? Why should you force taxpayers, some of whom can barely make a living, to pay examination fees for your child?”

The Treasury CS justified the decision as necessary for “fiscal responsibility and fairness” in government spending, though he provided no details on how student neediness would be determined or what safeguards would prevent eligible students from being excluded.

When President Kenyatta introduced the waiver in 2015 for public school students and extended it to private schools in 2017, the government allocated Sh4 billion annually to cover examination costs.

This figure has since grown to Sh5 billion over the past two years as student enrollment surged under the 100 percent transition policy.

The waiver eliminated fees that previously cost families Sh800 for primary school examinations and up to Sh2,700 plus Sh400 per subject for secondary school tests. Its removal represents a significant financial burden for families already struggling with Kenya’s rising cost of living.

Examining the numbers

The policy’s success in increasing access is undeniable. Kenya National Examinations Council (KNEC) CEO Dr. David Njeng’ere highlighted how candidature has “significantly increased over the 10 years the waiver has been in use.” By 2026, the Ministry of Education projects over three million learners will sit for national examinations across all levels.

However, this growth has strained KNEC’s resources. The council has struggled to pay contracted examination officials due to what Njeng’ere describes as inadequate funding, with the organization receiving lump-sum grants regardless of candidate numbers rather than per-capita allocations.

“We never had problems prior to 2015 when candidates used to pay individually. We’re four months to the exams and we still don’t have money,” Njeng’ere stated, revealing the financial pressures behind the policy shift.

Concerns mount

National Parents Association chairperson Silas Obuhatsa warned of potentially devastating consequences, drawing parallels to the troubled higher education funding model currently facing legal challenges.

“This policy shift could become a major problem for parents. Some may be forced to withdraw their children from school, which could result in increased dropout rates, especially among vulnerable learners,” Obuhatsa cautioned.

He emphasized the complexity of means-testing, noting that even private school students may be on scholarships or sponsorships, making accurate need assessment challenging.

“How will the government, particularly at the basic education level, accurately determine who can and cannot afford to pay exam fees?” he questioned.

The proposed examination fee model closely resembles the controversial university funding system that replaced blanket government support with a four-tier classification system ranking students as vulnerable, extremely needy, needy, or less needy.

That model has faced implementation challenges, legal disputes, and criticism for leaving thousands of students to fund their education independently.

The higher education funding model’s troubled rollout serves as a cautionary tale for the examination fee changes, suggesting potential administrative difficulties and access barriers for eligible students.

The policy reversal comes amid President William Ruto’s broader economic reforms aimed at reducing government expenditure and targeting subsidies more precisely.

However, critics argue that removing universal access to examinations—a cornerstone of educational equity—undermines the administration’s commitment to inclusive education.

The timing is particularly sensitive given Kenya’s economic challenges and the government’s emphasis on human capital development as a driver of economic growth.

Education stakeholders worry that reintroducing financial barriers at the examination level could reverse gains in enrollment and transition rates achieved over the past decade.

Implementation timeline

While Mbadi assured that funding exists for this year’s examinations and that “parents should not panic,” the uncertainty has already created anxiety among stakeholders.

The policy is set to take effect next year, giving the Ministry of Education limited time to develop and test the means-testing criteria.

The lack of public participation in the decision-making process has drawn criticism, with parents’ representatives calling for meaningful consultation before implementation.

This echoes broader concerns about the government’s approach to education policy reforms without adequate stakeholder engagement.

As Kenya prepares for this significant policy shift, several critical questions remain unanswered: How will need be accurately assessed? What appeals process will exist for disputed classifications? How will the government prevent eligible students from falling through administrative cracks?

The success or failure of this policy change will likely influence broader debates about the role of government in ensuring educational access and equity in Kenya.

With over three million students expected to take national examinations in 2026, the stakes for getting implementation right could not be higher.

For now, parents, students, and education stakeholders anxiously await details on how this fundamental shift in examination funding will unfold, hoping that the government’s promise of targeted support will not inadvertently create new barriers to educational achievement for Kenya’s young people.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoAlleged Male Lover Claims His Life Is in Danger, Leaks Screenshots and Private Videos Linking SportPesa CEO Ronald Karauri

-

Lifestyle2 weeks ago

Lifestyle2 weeks agoThe General’s Fall: From Barracks To Bankruptcy As Illness Ravages Karangi’s Memory And Empire

-

Grapevine4 days ago

Grapevine4 days agoRussian Man’s Secret Sex Recordings Ignite Fury as Questions Mount Over Consent and Easy Pick-Ups in Nairobi

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoEpstein Files: Sultan bin Sulayem Bragged on His Closeness to President Uhuru Then His Firm DP World Controversially Won Port Construction in Kenya, Tanzania

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoKRA Can Now Tax Unexplained Bank Deposits

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoEpstein’s Girlfriend Ghislaine Maxwell Frequently Visited Kenya As Files Reveal Local Secret Links With The Underage Sex Trafficking Ring

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoState Agency Exposes Five Top Names Linked To Poor Building Approvals In Nairobi, Recommends Dismissal After City Hall Probe

-

Investigations17 hours ago

Investigations17 hours agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy