News

Audit Reveals How Billions Are Lost to Ghost Workers Across Kenya’s Public Sector

Latest government reports expose systematic looting through fraudulent payrolls as counties spend Sh6.5 billion on non-existent employees

A damning audit has revealed that billions of shillings continue to hemorrhage from Kenya’s public coffers through an elaborate network of ghost workers, fake schools, and fraudulent health facilities, despite existing financial safeguards.

The comprehensive review by the Auditor-General and Controller of Budget shows that 22 of Kenya’s 47 counties spent Sh6.5 billion in the first nine months of the 2024/25 financial year paying workers who exist only on paper, with the crisis described by Treasury officials as “a pandemic” affecting most county governments.

Nairobi Leads in Ghost Payments

Nairobi City County topped the list of offenders, channeling Sh629.63 million through manual payrolls outside the electronic system, representing 4.9 percent of its total wage bill. Busia County followed with Sh569.91 million (21 percent of total emoluments), while Uasin Gishu processed Sh493.6 million through irregular payrolls.

“Manual payroll is prone to abuse and may lead to the loss of public funds where proper controls are lacking,” Controller of Budget Margaret Nyakang’o warned in the latest budget implementation report.

The Ghost Worker Web

According to the Public Financial Management Reforms Secretariat, ghost workers fall into two categories: real people fraudulently placed on payrolls who may not even know they’re being paid, and entirely fictional employees created by corrupt officials.

The problem extends beyond salaries to pension schemes, where ghost workers naturally graduate to retirement benefits while others are directly added by managers with access to the systems.

In Nyamira County, leadership faced Senate scrutiny after losing Sh2.8 billion to ghost worker salaries in the 2018/2019 financial year alone. Meanwhile, Vihiga County’s audit revealed 426 employees earning Sh32 million who could not be traced to their supposed duty stations.

Schools and Hospitals Join the Fraud Network

The ghost worker phenomenon extends beyond county payrolls into education and healthcare sectors. A special audit covering 2020/21 to 2023/24 found that over Sh20 million was disbursed to 14 non-existent schools that existed only on paper with functional bank accounts.

“The ghost schools are the ones in the system but when we got to the ground, we did not find them,” explained Justus Okumu, director of audit at the Office of the Auditor-General. “The schools are getting the capitation fees but education officers could not show us where they exist.”

Former Education Cabinet Secretary George Magoha estimated that manipulation of student enrollment figures alone costs the country over Sh750 million annually.

Healthcare Fraud Escalates

The healthcare sector has witnessed perhaps the most brazen fraud attempts, with over 1,000 hospitals sanctioned for trying to steal Sh10.6 billion from the Social Health Authority (SHA).

Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale revealed that fraudulent practices included multiple billing, ghost patients, collusion between SHA officers and non-existent facilities, and inflation of medical claims through altered information.

“Fraud is a major threat to health insurance, both public and private,” Duale stated, announcing that digital systems have helped identify and close fake facilities while investigations continue for prosecution and recovery of stolen funds.

Despite the Public Finance Management Act, Public Audit Act, and National Treasury regulations designed to prevent such theft, the systematic looting continues unabated.

The wage bill crisis has reached alarming proportions, with 16 counties spending more than 50 percent of their revenues on wages, severely constraining operational and development budgets. Only 11 counties complied with the mandated 35 percent wage bill ceiling.

Unsupported employee compensation has reached Sh4.2 billion across the counties, indicating the vast scale of irregular payments flowing through the system.

Education Cabinet Secretary Julius Ogamba acknowledged the crisis, saying his ministry has delayed fund disbursements to schools while cleaning data to eliminate ghost institutions.

“We have to be more careful than before. We must verify and confirm the number of learners and schools,” Ogamba stated.

The Ministry of Health has implemented biometric identification systems, geofencing of facilities, and digitized records to create what Duale calls “a single source of truth” for licensed healthcare providers.

The audit findings highlight the persistent challenge of financial controls in Kenya’s devolved governance system. Manual payrolls, designed for legitimate purposes such as onboarding new staff and paying casual workers, have become vehicles for systematic theft.

The Controller of Budget noted that manual systems create opportunities for irregular recruitment, employment of casual laborers beyond legal limits, and improper compensation through inflated allowances.

As investigations continue and digital systems are implemented, the question remains whether these measures will be sufficient to plug the billion-shilling hemorrhage that has characterized Kenya’s public financial management for years.

The government has promised prosecutions and recovery of stolen funds, but previous similar promises have yielded limited results in stemming the tide of public resource theft through ghost workers and fraudulent schemes.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Economy2 weeks ago

Economy2 weeks agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoKPC IPO Set To Flop Ahead Of Deadline, Here’s The Experts’ Take

-

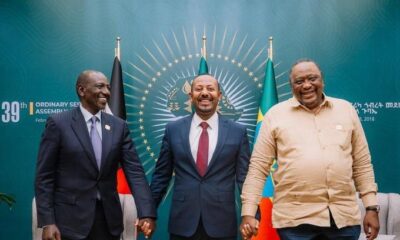

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoPresident Ruto and Uhuru Reportedly Gets In A Heated Argument In A Closed-Door Meeting With Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours