News

“At the Wrong Place at the Wrong Time” – Nairobi Court Acquits Five in Cartel Ivory Case

By Chris Morris October 1st, 2025.

If an ivory seizure could ever be described as ‘understated’, this would be the one.

It was not a large seizure. By international standards, 216.76 kilogrammes (kg) of ivory falls under the 500 kilogrammethreshold to be classified as ‘major’. But to wildlife crime investigators and pundits of the illegal wildlife trade in Kenya, there was no doubting the significance of the arrests.

On the evening of June 26th, 2017, Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) officers of the Special Crime Prevention Unit (SCPU), received information of a house in Nairobi’s Utawala Estate ( close to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport) whose occupants had elephant ivory. The SCPU team maintained vigil on the home over night.

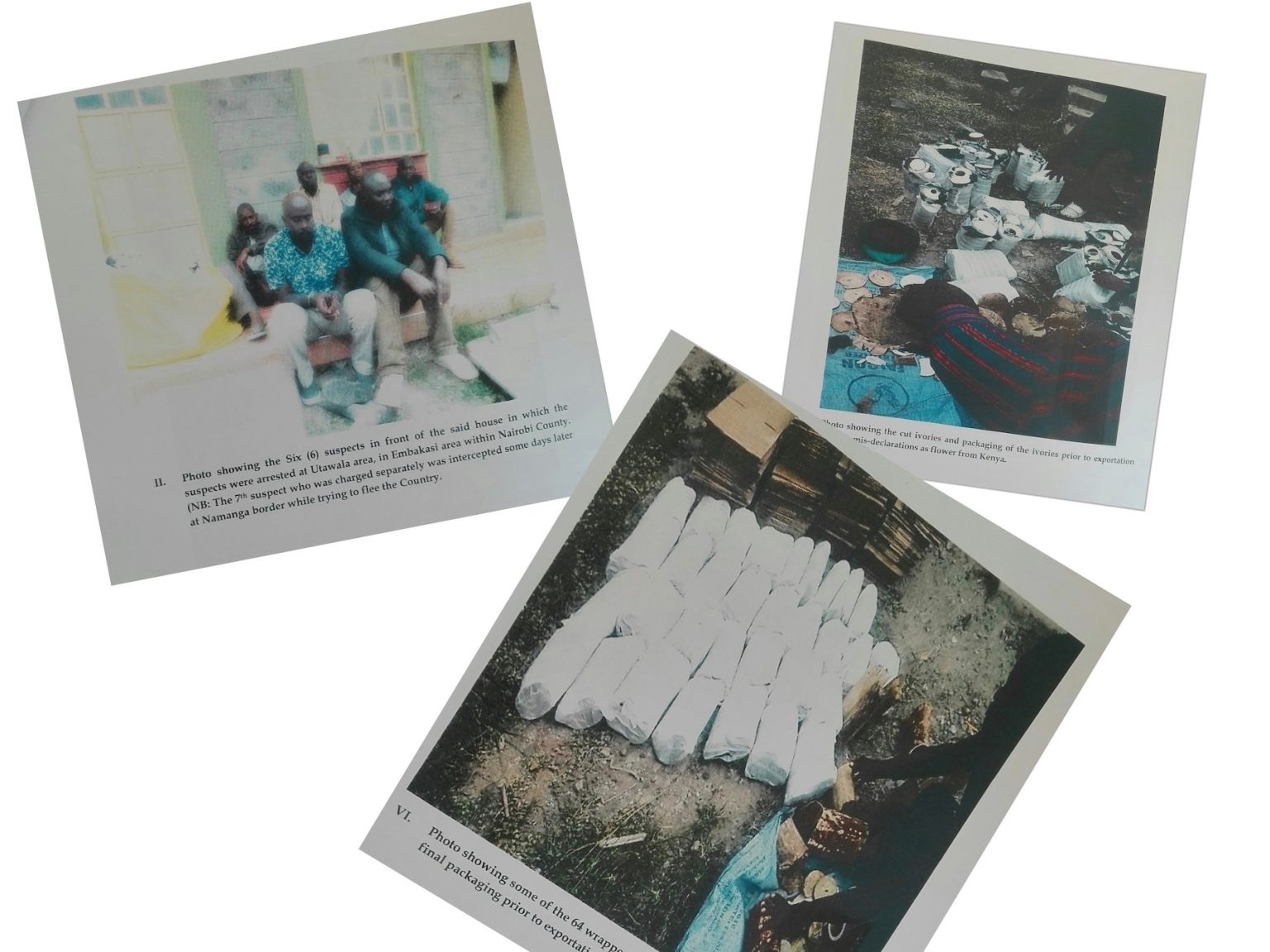

The following morning, at approximately 10:30hrs, a team of four SCPU officers entered the compound and one of two homes within to find Julius Adika (the tenant), Wesley Adwenya, and Hilary Karani, actively engaged in the packaging of elephant ivory for air freight out of Kenya. Ronson Njue and Rawlings Ogondi (brother to Adwenya) were found in close proximity and also arrested. An Isuzu pickup truck, believed to be the transport vehicle for the ivory,was parked in front of the house. Njue was the suspected driver.

In the ensuing search, 64 pieces of packaged elephant tusks, 25 cylindrical shaped cut tusks, 16 hollow shaped tusks, rolls of white and grey cello tape, and assorted cartons were found in the master bedroom. In the smaller bedroom were found weigh scales, a grinder, and 11 saw blades. In the sitting area was a strapping machine and band saw, while a generator was discovered in the kitchen. Tobacco powder, for disguising the scent of the ivory, was located in the Isuzu pickup.

Upon conclusion of the search, investigators had Wesley Adwenya call the believed owner of the ivory, Abdinur Ibrahim Ali alias Abdinoor Ibrahim Ali, for a fabricated, urgent, off-site meet. The deception played out and Ibrahim Ali was arrested by the SCPU officers and taken to the Utawala seizure site. KWS officers later attended the scene to weigh the ivory and take custody of all exhibits.

It appeared to be the classic definition of a “smoking gun” type seizure. Providence continued to smile down on investigators when three days later, Ahmed Mahubub Gedi alias Ahmed Mohamed Salah, the money man of the operation, was detained at the Namanga border crossing, attempting to flee Kenya for Tanzania and further to his home in Nampula, Mozambique. It would not be hyperbole to state that Kenyan law enforcement had pulled off arguably the most significant ivory trafficking organised crime arrest of recent years.

The seven accused, Julius Abluu Adika, Abdinur Ibrahim Ali, Wesley Silvanus Adwenya, Hillary Karani, Rawlings Innocent Ogondi, Ronson Njue Mati, and Ahmed Mahubub Gedi were charged before Kibera Court #2 Senior Principal Magistrate(SPM) Esther Boke with ‘Possession and Dealing in Wildlife Trophies’ as well as ‘Acting in Concert with Others’ contrary to the Prevention of Organized Crimes Act. The case was to be known as MCCR/1649/2017 – Republic vs. Julius Abluu Adika & Abdinur Ibrahim Ali & 5 others.

International Connections

Police statements and media reports continued painting a picture of the transnational criminal organization involved. Abdinur Ibrahim Ali was reported as the main dealer operating with Guinean nationals in Uganda as well as Chinese nationals in Kenya working under false permits. Ibrahim Ali had told investigators that he worked with a mining company known as Frontier Resources Ltd. located in Bangali, a five hour drive east of Nairobi in the direction of the Somali border.

Ahmed Mahabub Gedi, was publicly identified as a Somali national arrested with fraudulently acquired Kenyan documents and the link person between Kenyan ivory traders and China and Thailand markets. The head of the SCPU told the press that most of the ivory had originated from Meru National Park. A separate report had it being sourced from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The initial investigation into the arrest/seizure of Ibrahim Ali et al appeared to continue in exemplary fashion. Ahmed Mahubub Gedi provided a detailed cautioned confession to investigators stating that he operated a money transfer business and international travel agency. He was in Kenya for the sole purpose of being the financial go between for the West African TCO and Abdinur Ibrahim Ali. Gedi received USD $26,000 through Amal Express, Eastleigh branch, in Nairobi, from a named West African broker in Bangkok, Thailand. He retained $1000 as his fee and gave the remainder to Ibrahim Ali on the afternoon of June 23rd.

Wesley Adweyna also provided a cautioned statement, telling investigators that he had been contacted by Ibrahim Ali requesting a consignment be sent to Bangkok,Thailand. Thereafter, Adwenya picked up the ivory from Ibrahim Ali at Tusky’s Mall at Embakasi on the afternoon of June 25th (or June 23rd) and delivered it to the Utawala site accompanied by Ogondi and Hillary Karani.

The SCPU investigation was handed over to KWSinvestigators on July 6th. At about the same time, the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC), with support from an international NGO, began a parallel investigation that included a probe into possible proceeds of crime and money laundering offences. Abdinur Ibrahim Ali and Frontier Resources Ltd. were the centre point of that investigation. It was discovered that Ibrahim Ali was more than just a worker for Frontier Resources Ltd. but was also a signatory on their bank account. He was as well the signatory on bank accounts with two other Kenyan companies. Financial record analysis by the EACC indicated what appeared to be suspicious transactions in the millions of shillings to accounts outside of Kenya, transactions suggestive of money laundering.

Ibrahim Ali’s connection to the West African cartel and specifically to Liberian national, Moazu Kromah, was already known. Kromah had been arrested in February 2017 in Uganda, found in a fortified Kampala home with his brother and nephew and 1.3 tonnes of ivory. It was through this arrest, that evidence in the form of documents and emails established previous ivory trafficking dealings between Kromah, Abdinur Ibrahim Ali, and Ahmed Mahubub Gedi (known to Kromah as ‘Ahmedi Fallah’).

The EACC investigation also found links to a Kenyan national, residing at the time in Zambia, and connected to a furniture business, registered in Hong Kong, but with a physical address in Guangdong, China. It received USD 1.2 million between August 2016 and March 2017 with money transfers received from Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.

The Nairobi Connection

At the micro-level, there was a close knit relationship between the remaining five accused. Julius Adika, the tenant of the raided home, was the uncle to brothers Wesley Adwenya and Rawlings Ogondi. He was said to be in the vegetable exportation business.

Wesley Adwenya, had a JKIA connection through a previous flower exportation business that ran for a few years from 2013. He had told investigators that he had met Abdinur Ibrahim Ali one year previous and had provided advice on clearing and forwarding freight from JKIA.

His brother, Rawlings Ogondi, stated that he was unemployed but had previous work experience at DHL Global Freight and the Swissport Cargo Centre at JKIA. Hillary Karani told police that he had gone to school with Wesley Adwenya and met him on a regular basis at the airport where he was now doing casual loading and off-loading work. These four men had known each other for many years and were all from the county of Vihiga. Ronson Njue, the driver of the Isuzu pickup, was a close neighbour of Julius Adika and did transportation work on behalf of the vehicle owner, Raphael Mugenge Kahi. Kahi, a government civil servant with the Ministry of Lands, knew Julius Adika as they came from the same village, also in Vihiga county.

Kahi became a witness for the prosecution. While his written statement for investigators indicated his involvement as an innocent third party, his testimony indicated a likelihood of complicity.

“At the wrong place at the wrong time”

The trial lasted eight years. Typically a trial of that duration is an indicator of compromised process, especially so when the prosecution comprises of only 14 witnesses.

On July 23rd, 2025, Chief Magistrate (CM) Ann Mwangi found the remaining five accused not guilty. In her summation, she wrote that none of the accused (excluding the deceasedAdika) had been found in possession of the recovered tusks. She believed that the phone communication evidence was not indicative of ivory business and suggested that it may have “been tailored to exclude many other transactions”. She similarly believed that the financial transactions, based on the accused’s usage of the Mpesa mobile money banking system, was also not indicative of ivory trafficking.

Her justification for handing down what seemed to be both an incredulous and dubious verdict was based primarily on the testimony of the two arresting SCPU officers. CM Mwangi wrote: “this is not evidence of serious officers who desires to proof (sic) that indeed all the accused persons were involved in the ivory trade” and that it was “sad that the two arresting officers had contradicted on how the 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th accused were arrested.” On this count, she was correct. The evidence presented by the police was decimated by its contradictions, inconsistencies, and omissions.

In light of the vacuum of veracity from police, CM Mwangi opted instead to believe the version presented by all accused, a version that they had eight years to craft, a version that bore little resemblance to their initial statements to police , a version afforded them through the reported passing of Julius Adika, a version that included Adwenya, Karani, and Ogondi, just by chance, attending the Utawala house full of ivory to visit an ailing relative, Adika.

She believed that without evidence to the contrary, Adika was guilty as the ivory had been found in his house and that all remaining five accused persons were victims of association.

She concluded that “the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th accused were at the wrong place at the wrong time” and added that she found the deceased Julius Adika guilty posthumously of ‘Possession and Dealing in Wildlife Trophies’. A posthumous finding of guilt had never been seen in an ivory case. Was she serious?

Hoisted By Their Own Petard

It was sadly ironic that in a trial bereft of evidence, that the final blow to the prosecution would come from its own hand.

With the EACC investigation never being permitted to progress further than the investigative stage, the prosecution was wholly reliant on the evidence of the SCPU and KWS. That consisted primarily of two elements; the SCPU officers who made the arrests and phone communications records. This phone data included the frequency of calls between the seven accused, financial transactions between the accused on the Mpesa mobile money platform, and location data that was intended to indicate where the accused were when various calls and transactions were being made. The phone data did not include SMS text messages (not withstanding that it been collected) or any mined data.

The prosecution began unraveling at the point when a contradictory version of the circumstances of arrest was presented by the second SCPU officer. It now became unclear what Adika, Adwenya, and Karani were doing inside the house on police entry, the arrest location of Njue and Ogondi, and even the composition of the police arrest team. The testifying officers also contradicted their own statements written on the date of the incident, statements that one might have expected them to read as part of their trial preparation. They were consistent, however, that their team had maintained an all night vigil of the Utawala home and that they had seen no activity until just prior to their 10:30 hrs raid on the morning of June 27th.

The phone data, however, indicated otherwise, intimating that Adwenya, Ogondi, and Karani did not spend the night at the target home with Adika as stated by SCPU, but had arrived approximately 45 minutes prior to the raid, and two of them by vehicle. Phone calls had been registered in the early morning hours between Adika, Adwenya and Njue casting further doubt on the truthfulness of the police. In addition, at 09:45 hrs, Hillary Karani sent a text message to Adwenya: “Nimefika” (I have arrived), clearly not a message one would send to another who you were allegedly standing beside while packaging ivory. That was a text message that was not entered into evidence. The court was left questioning the conduct of the police in the overall operation. Did they actually conduct an all night vigil on the Utawala home and incompetently miss the early morning comings and goings, or was it a fabricated version to bolster the case?

The phone data evidence, unsupported as it was, did demonstrate the connections between the group of seven through their call frequency but was not proof of any type of criminal conspiracy. The data on the financial transactions between the group was remarkable only in its lack of any shilling amount that could possibly be construed as having anything to do with ivory trafficking. The USD $26,000 cash obtained by Gedi for Ibrahim Ali was referenced in one of Gedi’s SMS text’s but because it was to a person outside of the group of seven was not presented to the court. The presented phone location data was also weak and inconsistent due to there being “gaps” in that information. Overall, the presented phone data evidence did nothing to prove possession or dealing in elephant ivory or criminal conspiracy.

The pillars on which the prosecution was based had crumbled.

Summary of Evidence

There was essentially no evidence during the eight-year trial that connected primary accused, Abdinur Ibrahim Ali, to the ivory. A SMS text, never seen by the court, sent by Ibrahim Ali to Adwenya at 10:15 hrs on the morning of the seizure stating: “Don’t change the booking”, may have been something to build on.

There was no evidence that Adwenya was engaged with Ibrahim Ali in any other business apart from trucking and no evidence was produced by the prosecution to refute that.

There was no evidence presented to the court to suggest that any investigation had been conducted regarding the origin of the ivory, the air waybill or other booking details, its final destination, or how it came to be in the house of Julius Adika.

The tainted evidence of the police negated the involvement at the arrest site of Wesley Adwenya, Hillary Karani and Rawlings Ogondi. The was no evidence to indicate that the Isuzu pick-up that was found in the compound was there for the purpose of delivering the ivory to JKIA and so no evidence against the driver, Ronson Njue.

Julius Adika reportedly passed away in April 2022. While this may have been true, two other previous major ivory prosecutions had also seen either accused persons or witnesses of significance pass away during trial. In this trial, the passing of Adika enabled the remaining five accused to place the mantle of responsibility on him virtually unchallenged.

Ineptitude or Malfeasance

There were multiple breakdowns in this prosecution and all key players, the DCI, KWS, Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP) and at least two magistrates, share culpability.

The manner in which primary accused, Abdinur Ibrahim Ali, was handled also bears comment. From the day of arrest, a thread appeared that continued throughout the investigation and trial; the downplaying and censorship of Abdinur Ibrahim Ali’s involvement.

On the day of arrest, the only cautioned statement was taken from Adwenya, not from Ibrahim Ali who was the more significant arrest. On the day of arraignment, the lawyer for Ibrahim Ali requested from the court that his photo and that of his co-accused not be taken. This is a privilege not afforded to even arrested public figures or corrupt police who find themselves in the prisoners dock. The prosecution and court quietly acquiesced.

In the final two page (legal) police cover report on the incident, Ibrahim Ali’s name, circumstances of arrest, and involvement, were omitted. In the same vein, he received scant attention in the summation of CM Mwangi’s final judgement. While perhaps explainable considering the lack of evidence against him, that fact in itself should have drawn comment from the magistrate.

The breakdown between the two SCPU officers from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations over the circumstances of arrest was incomprehensible. Directed perjury is the most logical explanation.

The Kenya Wildlife Service told the court that they took over the investigation on July 6th, 2017, ten days after the arrest. Based on trial evidence, they did little to advance the investigation. There was no indication that KWS conducted any investigation or explored any avenues relating to how or for what duration, the West African TCO, through Abdinur Ibrahim Ali, had been shipping ivory through Jomo Kenyatta International Airport as ‘flowers’.

Ahmed Mahabub Gedi, the seventh accused and MoazuKromah’s financial broker, was never apprehended. His name was added to the Interpol Red Notice list but deficient of detail; no photograph (KWS had his passport), no alias, no physical descriptors, no offence listing, no mention that he was a resident of Mozambique. His name was removed prior to trial conclusion.

The conduct of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions also bears examination. In light of a prosecution practically devoid of evidence, how were the initial charges approved? And why would they allow the trial to continue to conclusion after the presentation of contradictory evidence by the police, contradictions found existent in their initial written statements?

The first public and obvious indicator of malfeasance in this prosecution actually came from a magistrate. On a Friday afternoon July 7th, 2017 in what was reported as an ‘in chambers’ session in court 1, Ahmed Mahabub Gedi alias Ahmed Mohamed Salah, alias Ahmedi Fallah, was released on a cash bail of USD $10,000.

It is difficult to envisage a criminal arrest with more compelling grounds for custodial remand. Ahmed Mohamed Salah, with numerous aliases, arrested at a Tanzanian border point while in the process of fleeing justice in Kenya, in possession of fraudulent Kenyan identification, a resident of Mozambique for five years, no fixed address in Kenya, a major player in a TCO, illegally in Kenya for the sole purpose of committing criminal offences involving the trafficking of 216.76 kg of ivory to Southeast Asia. He was never seen again.

The second injudicious decision came from SPM Samson Temu. SPM Temu took over the trial in May 2023 and heard the remaining three witnesses. He made the decision that a prima facie case had been established and that there was a case to answer for the defence. How was that even possible, particularly in reference to Abdinur Ibrahim Ali?

Can it be coincidence for all involved criminal justice players to suffer debilitating failures in the same case?

Reprise

Republic vs. Julius Abluu Adika & Abdinur Ibrahim Ali & 5 others followed the ignominious footsteps of the Republic vs. Abdulrahman Mahmoud Sheikh and eight others acquitted in a Mombasa court in October 2023 of exporting 3127 kg of ivory in 2015. That case also suffered from a shameful lack of evidence, involved direct linkages to the West African cartel, and fell prey to outside interference.

Lack of evidence to convict is not an uncommon trait in major ivory trafficking trials within the Kenyan criminal justice system. Significant doubt on the cause of that lack of evidence is just as common.

What is not common is the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission’s involvement in a ivory trafficking investigation also being investigated by KWS. The optics would indicate that someone in the decision making process was concerned that this particular investigation was vulnerable to forces not within the justice system. Unfortunately, while that foresight bore some fruit, it was trumped from a higher level before the card revealing transnational organised crime evidence could be played.

Past investigations and prosecutions into major wildlife trafficking events involving TCO’s have met with similar pitfalls and more often than not, failure to convict. While Kenya has been known globally as a staunch opponent to the ivory trade, its record in the courtroom prosecuting major ivory cases is a manifestation of the opposite.

What began as an exemplary seizure with arrests of two significant players of the West Africa TCO, descended into sadly farcical acquittals with the guilt pinned on a dead man who had no say in his defense.

“At the wrong place at the wrong time.” Embarrassing really.

A special thanks to Judy Muriithi Wangari for her invaluable contribution.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoRussian Man’s Secret Sex Recordings Ignite Fury as Questions Mount Over Consent and Easy Pick-Ups in Nairobi

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy

-

Economy1 week ago

Economy1 week agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Africa2 weeks ago

Africa2 weeks agoFBI Investigates Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s Husband’s Sh3.8 Billion Businesses in Kenya, Somalia and Dubai

-

Grapevine3 days ago

Grapevine3 days agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoSifuna, Babu Owino Are Uhuru’s Project, Orengo Is Opportunist, Inconsequential in Kenyan Politics, Miguna Says