Investigations

The US Hand Revealed in The Sh8.2 Billion Drug Bust in Mombasa

The intelligence that led to the interception of the Igor was generated by surveillance systems Kenya does not own and cannot access independently.

When six Iranian nationals appeared at the Shanzu Law Courts on Tuesday morning, the courtroom drama that unfolded revealed far more than just another drug trafficking case.

It exposed the intricate web of American intelligence operations in East African waters and raised uncomfortable questions about sovereignty, jurisdiction and the shadowy world of international maritime surveillance.

The suspects unanimously rejected a Baluchi-English interpreter provided by the US Naval Criminal Investigative Service, accusing him of failing to communicate effectively . Their protest, delivered in unison through another translator, marked the first public acknowledgment of Washington’s direct involvement in what has become Kenya’s second-largest narcotics seizure in history.

The presence of an NCIS representative in the Mombasa courtroom was no accident. An NCIS official confirmed to the court that the interpreter had been contracted by the agency to assist with the suspects’ communication.

Some of the 1,024 kilogrammes of synthetic drugs seized from six Iranian crew members aboard a vessel. The haul, estimated to be worth Sh8.2 billion, was seized about 650 km off the shore of Mombasa.

This seemingly mundane detail about translation services pulled back the curtain on a sophisticated multinational operation that had been tracking the stateless dhow Igor for weeks before Kenyan naval vessels finally cornered it 630 kilometres east of Mombasa.

The operation that netted 1,024 kilogrammes of crystalline methamphetamine with 98 percent purity did not begin in Nairobi or even Mombasa. Intelligence was shared between the Regional Narcotics Interagency Fusion Cell in Bahrain and the Regional Coordination Operations Centre in Seychelles before Kenyan authorities were brought into the picture. INTERPOL coordinated operational support from the US Naval Criminal Investigative Service , establishing a clear command structure that placed American intelligence assets at the heart of the interdiction.

The Regional Narcotics Interagency Fusion Cell operates out of Naval Support Activity Bahrain, the headquarters of the US Fifth Fleet. The cell is a joint US Department of Defence and law enforcement team that includes personnel from US Naval Forces Central Command, the Combined Maritime Forces, and law enforcement agency partners . Its mandate extends far beyond the Arabian Gulf, reaching into the Western Indian Ocean where Kenya’s territorial waters meet international shipping lanes used by drug trafficking syndicates.

What unfolded on October 21 when the Kenya Navy intercepted the dhow was the culmination of what intelligence sources describe as weeks of satellite surveillance, signals intelligence and coordinated tracking involving multiple naval assets. The operation, codenamed Bahari Safi 2025.01, deployed the Kenya Navy Ship Shupavu and a Dornier Maritime Patrol Aircraft operated by the Seychelles Coast Guard. But behind this regional collaboration lay American technological capability that few African nations can match.

The suspects, identified as Jasem Darzaen Nia, Nadeem Jadgai, Imran Baloch, Hassan Baloch, Rahim Baksh and Imtiyaz Daryayi, had been navigating what they believed were anonymous waters. The dhow carried no flag, no registration, no identification. In the murky world of maritime drug trafficking, such vessels are known as dark ships, invisible to standard tracking systems, relying on the vastness of the ocean for protection.

They had not counted on the reach of American surveillance architecture. The vessel had been on what DCI Director Mohamed Amin described as an international radar. Foreign security agents were spotted at the Port of Mombasa during the press briefing announcing the navy’s interception , their presence a visible reminder that this was never purely a Kenyan operation.

Director of Criminal Investigations boss Mohamed Amin said the operation was carried out by a multi-agency team comprising the Anti-Narcotics Unit, the Kenya Navy, the Coast Guard, Port Police, the National Intelligence Service, the Kenya Revenue Authority and the Kenya Ports Authority Police, in cooperation with regional partners . That careful diplomatic phrasing, regional partners, is the language of plausible deniability, the bureaucratic veil drawn over American operational involvement.

The drug haul tells its own story about the sophistication of the trafficking network. The 769 packages were wrapped in black polythene and sealed with yellow tape bearing the label “100 per cent roasted and grounded Arabica coffee.” The methamphetamine, valued at Sh8.2 billion on the street, was destined for markets somewhere in East Africa, part of a booming trade that has seen synthetic drugs increasingly displace traditional narcotics like heroin and cocaine.

Inspector Shadrack Kemei of the Anti-Narcotics Unit has obtained court orders to forensically examine seven mobile phones recovered from the suspects, including a Thuraya satellite phone and a GPS device. These gadgets, investigators believe, contain the digital breadcrumbs that will lead to the financiers and masterminds of the operation. Two of the suspects arrived without identification documents, adding another layer of mystery to their origins and intentions.

Five of the six Iranians accused of trafficking meth when they appeared at the Shanzu Law Courts on October 28, 2025.

The rejection of the NCIS interpreter by the Iranian suspects was not merely a translation dispute.

The suspects complained that the court would say something lengthy, but the interpreter only relayed a very brief version , raising questions about what information was being filtered or withheld.

Chief Magistrate Anthony Mwicigi was forced to accept the services of Amin Ahmed Juneja, a veteran interpreter who had previously worked on the Sh1.3 billion heroin case involving the vessel Amin Darya, leaving the American interpreter stranded in the courtroom.

The incident highlights the delicate balance Kenya must maintain between accepting crucial intelligence and technical assistance from foreign partners while preserving its judicial sovereignty.

The presence of NCIS personnel in a Kenyan courtroom, contracting interpreters for suspects in a Kenyan prosecution, raises questions that Interior Cabinet Secretary Kipchumba Murkomen has not yet addressed.

NCIS agents were the first US law enforcement personnel on the scene at the USS Cole bombing, the Limburg bombing and the terrorist attack in Mombasa, Kenya.

The agency has maintained a presence in East Africa for decades, operating from field offices across the region, often in cooperation with local law enforcement but answering ultimately to the Secretary of the Navy in Washington.

Kenya has increasingly become a focal point for American counter-narcotics operations in the Indian Ocean.

The country’s strategic location, its improving naval capabilities and its willingness to cooperate with Western intelligence agencies make it an ideal partner for operations targeting drug trafficking routes that connect Afghanistan’s opium fields, Iran’s methamphetamine labs and the consumer markets of East and Southern Africa.

But this partnership comes with costs that are rarely discussed in public.

The intelligence that led to the interception of the Igor was generated by surveillance systems Kenya does not own and cannot access independently.

The analysis that identified the vessel as a drug carrier was performed in facilities in Bahrain and Seychelles, far from Kenyan oversight.

Even the interpreter who appeared in court to facilitate justice was a contractor for a foreign military agency.

The six Iranians will remain in custody for 30 days while investigators complete their work.

They have requested boiled rice without cooking oil and bread during their detention, a small human detail in a case that spans continents and involves intelligence agencies from multiple countries.

They told the court they had provided police with all necessary information to facilitate investigations, though what that information contains remains sealed in the files of the Anti-Narcotics Unit.

The drugs, once the investigation and prosecution are complete, will be publicly destroyed. Interior CS Murkomen has already announced this, a symbolic gesture meant to demonstrate Kenya’s commitment to fighting the narcotics trade.

But the destruction of one shipment, however large, will not dismantle the networks that produced it, financed it and directed it toward East African shores.

The real question that emerges from the courtroom drama in Shanzu is not whether Kenya should cooperate with foreign intelligence agencies in fighting drug trafficking.

The answer to that is obvious in a world where criminal networks operate across borders with impunity.

The question is whether that cooperation is happening on terms that preserve Kenyan sovereignty and serve Kenyan interests, or whether it has evolved into something else entirely, a dependency that allows foreign powers to project their law enforcement priorities into Kenyan territorial waters and Kenyan courtrooms.

The rejected interpreter, his contract with NCIS still valid but his services declined by the very suspects he was meant to help, stands as a metaphor for the contradictions inherent in this arrangement.

Kenya needs the intelligence, the technology and the operational support that partners like the United States can provide.

But accepting that help means accepting the presence of foreign agents in Kenyan institutions, foreign priorities in Kenyan operations and foreign influence in Kenyan justice.

The stateless dhow Igor is now impounded at Kilindini Port, its cargo seized, its crew detained.

But the networks that sent it are already planning their next shipment, their next route, their next attempt to move synthetic drugs through the porous borders and vast waters of East Africa.

And somewhere in Bahrain, in Seychelles, in intelligence fusion cells and coordination centres that most Kenyans will never hear about, analysts are tracking the next vessel, preparing the next interception, drawing Kenya deeper into a global war on drugs that has no clear end and no clear victor.

The Sh8.2 billion meth bust is a victory, certainly. But it is a victory that reveals as much about Kenya’s limitations as it does about Kenya’s capabilities.

And in the courtroom in Shanzu, where an NCIS interpreter was rejected by the very suspects he was contracted to help, we see the tensions and contradictions of a partnership that Kenya cannot do without but perhaps cannot fully control either.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Economy2 weeks ago

Economy2 weeks agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoKPC IPO Set To Flop Ahead Of Deadline, Here’s The Experts’ Take

-

Politics2 weeks ago

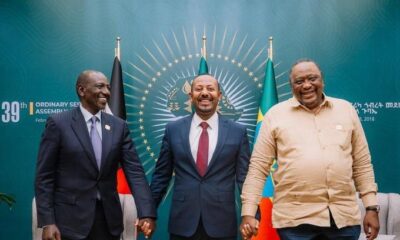

Politics2 weeks agoPresident Ruto and Uhuru Reportedly Gets In A Heated Argument In A Closed-Door Meeting With Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours