Investigations

Whose Drugs? Kenya Navy Seizes Drug Ship In Mombasa Carrying Sh8.2 Billion Meth

The Kenya Coast Guard Service provided maritime operational capabilities. Port Police secured the perimeter. The National Intelligence Service fed crucial intelligence.

Stateless vessel with six Iranian nationals intercepted 630 kilometres off Mombasa coast as multi-agency operation unmasks sophisticated transnational narcotics syndicate

The Indian Ocean has surrendered yet another deadly secret, and this time the numbers are staggering enough to make even seasoned narcotics investigators pause. On October 23, a ghost ship christened MV Igol, flying no flag and answering to no country, was prowling the international waters off Kenya’s coast when the long arm of the Kenya Navy reached out and grabbed it by the throat.

Inside its hull lay 1,024 kilograms of crystalline death. Methamphetamine, 98 per cent pure according to the Government Chemist. Street value: Sh8.2 billion, equivalent to USD 63 million.

Six Iranian nationals were on board, their vessel now impounded, their freedom forfeit, and their destination a mystery that investigators are racing to unravel before the trail goes cold.

The operation, executed 630 kilometres east of Mombasa under the ongoing campaign dubbed Bahari Safi, represents a seismic disruption to what appears to be a well-oiled transnational drug trafficking machine that has been using East African waters as a highway for synthetic narcotics destined for regional markets.

This is not some back-alley drug deal gone wrong.

This is industrial-scale trafficking, the kind that feeds addiction epidemics across continents, funds armed groups, destabilizes governments, and leaves a trail of broken lives in its wake.

Operation Bahari Safi Strikes Gold

The vessel had been on international radar for some time, its suspicious movements in the western Indian Ocean circuit flagging it as a priority target. Intelligence from regional and international partners filtered through to Kenyan authorities, painting a picture of a craft making calculated rounds, waiting for the opportune moment to make its delivery.

The Kenya Navy, working in concert with the Kenya Coast Guard Service, moved with military precision.

Kenya Navy Deputy Commander Brigadier Sankale Kiswaa was unequivocal about the operation’s success during a media briefing on Saturday at Mombasa port.

“In the operation by the multi-agency team and international police, we arrested the six Iranians who were escorted to Mombasa. Upon searching the hull, we found 1,024 kilogrammes of methamphetamine valued at more than Sh8.2 billion,” he declared, the seized packages stacked behind him like a monument to law enforcement triumph.

The multi-agency dragnet was impressive in its scope and coordination. The Anti-Narcotics Unit brought their specialized expertise.

The Kenya Coast Guard Service provided maritime operational capabilities. Port Police secured the perimeter.

The National Intelligence Service fed crucial intelligence.

The Kenya Revenue Authority stood ready to value the contraband. Kenya Ports Authority Police ensured seamless port operations.

And behind it all, international drug enforcement officers whose names and nations remain classified provided the initial tip-off that set the wheels in motion.

This was not a lucky break.

This was methodical, patient police work backed by cutting-edge surveillance and the kind of international cooperation that drug traffickers dread.

The Haul: 98 Per Cent Pure Death

DCI Director Mohammed Amin watched as his officers cut open sack after sack under the unforgiving Mombasa sun.

Inside were 769 packages of a crystalline substance that field tests confirmed to be methamphetamine.

The Government Chemist later confirmed what investigators suspected: this was not some diluted street product cut with baby powder and baking soda.

This was 98 per cent pure methamphetamine, laboratory-grade poison manufactured with precision and intended for maximum profit and maximum destruction.

“We shall continue to interrogate the six suspects, but we are yet to know the source of the drugs. The consignment was destined for one of the local markets,” Amin said, his carefully chosen words betraying the investigation’s complexity.

The drugs could have originated from any number of clandestine labs across Asia, where methamphetamine production has reached industrial scales.

Iran itself has emerged as both a transit country for Afghan opiates and increasingly a source of synthetic drug production, its isolated economy creating perverse incentives for criminal enterprise.

The street value calculation was staggering: Sh8.2 billion.

To put that in perspective, that is more than the annual health budget of several Kenyan counties combined.

That is enough money to build schools, hospitals, roads. Instead, it was earmarked to finance addiction, crime, and human misery across East Africa.

The Iranians: Six Men, A Thousand Questions

Six Iranian nationals were arrested on board. Their names have not been released pending court proceedings.

Some of the six Iranian crew members under tight security after a seizure of narcotics aboard an Iranian Vessel worth Sh8.2billion some 650 km off the shore of Mombasa.

Their mission remains under investigation.

They are expected to appear before a Mombasa court on Monday to face drug trafficking charges that could see them spend the rest of their productive lives behind Kenyan bars, far from home, their families, and whatever dreams they once harbored before they chose to crew a narcotics vessel across the Indian Ocean.

The vessel itself was stateless, a deliberate tactic used by traffickers to avoid jurisdictional complications. With no flag to fly and no home port to claim it, MV Igol existed in a legal grey zone that traffickers have long exploited.

Stateless vessels are the ghost ships of international crime, drifting through maritime law’s blind spots, answerable to no nation until someone with enough firepower decides to make them answerable.

“It is too early for me to say the destination was point A or B, it is still under investigations. But certainly, it was destined somewhere in this region,” Amin said, carefully avoiding speculation but acknowledging the elephant in the room: East Africa, with its porous borders, weak governance in certain corridors, and growing middle class with disposable income, was either the target market or a strategic transit point for onward distribution to Southern Africa or beyond.

Kenya Coast Guard Director Bruno Shioso was also present during the briefing, his presence underlining the maritime dimensions of the threat Kenya faces.

The Indian Ocean, vast and largely unpoliced, has become a superhighway for everything from arms to people to drugs. Every successful interdiction sends a message: these waters are not lawless.

The Poison: Understanding Methamphetamine’s Deadly Allure

Methamphetamine is part of a group of drugs known as amphetamine-type stimulants, and it represents the next frontier in Africa’s drug war.

Unlike heroin or cocaine, which require specific climates and crops to produce, methamphetamine is entirely synthetic.

It can be manufactured anywhere with access to precursor chemicals and a rudimentary understanding of chemistry.

This makes supply chains resilient and difficult to disrupt.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, methamphetamine induces feelings of euphoria, heightened energy and alertness while suppressing hunger and fatigue.

For impoverished communities where exhaustion is chronic and hope is scarce, the appeal is obvious and tragic.

Users report feeling invincible, capable, alive. The drug delivers everything poverty denies: energy, confidence, escape.

But the cost is catastrophic. Users may experience increased heart rate, high blood pressure, sweating, and irritability.

In large doses, methamphetamine can cause panic attacks, convulsions, seizures, and death.

Long-term use leads to malnutrition, severe weight loss, dental decay so severe users are left with rotting teeth, and psychological dependence so profound that users cannot imagine life without the drug.

Once chronic users stop taking methamphetamine, they often experience prolonged sleep followed by depression so crushing that many relapse just to make the darkness go away.

It is a cycle of destruction that tears apart families, destabilizes communities, and creates public health emergencies that cash-strapped African governments are ill-equipped to handle.

The 1,024 kilograms seized on MV Igol represents millions of doses. Millions of lives that will not be destroyed.

Some of the 1024 kilograms of synthetic drugs seized from six Iranian crew members aboard an Iranian Vessel worth Sh8.2billion some 650 km off the shore of Mombasa.

Millions of families that will not be torn apart. Millions of crimes that will not be committed to feed addictions that consume everything they touch.

The Pattern: Kenya Under Siege

This seizure comes just two weeks after four suspects linked to an international drug syndicate were arrested at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport for allegedly using the facility to smuggle cocaine.

The proximity of the two busts is not coincidental. It suggests Kenya is increasingly being used as a drug trafficking corridor, a development that should alarm policymakers and security strategists from Nairobi to Addis Ababa to Dar es Salaam.

Kenya’s geographic position makes it strategically valuable to traffickers. It sits at the crossroads of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Its ports are busy and relatively modern.

Its airport is a regional hub. Its roads connect to Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Somalia. For traffickers looking to move product across the continent, Kenya offers infrastructure, access, and opportunity.

But Kenya also offers something else: corruption vulnerabilities.

While this operation demonstrates the competence and dedication of Kenyan security forces, the reality is that billion-shilling drug shipments do not move without inside help.

Port officials who look the other way. Customs officers who accept bribes. Police who provide escort. Politicians who offer protection.

The drug trade corrupts everything it touches, and Kenya is not immune.

The Triumph: When Agencies Actually Work Together

Credit must be given where it is due.

This operation represents the best of inter-agency collaboration, a rarity in a country where turf wars between security agencies often undermine effectiveness.

The Kenya Navy’s maritime surveillance capabilities, the Kenya Coast Guard’s operational agility, the DCI’s investigative muscle, the National Intelligence Service’s intelligence gathering, and the coordination with international partners created a net that MV Igol could not escape.

“The fight against drug trafficking is an international effort, and we thank the Kenya Navy and other transnational drug enforcement officers for assisting in combating drugs,” Amin said, a rare acknowledgment of the intelligence-sharing that makes such operations possible.

“Cooperation with other regional teams made it possible to intercept the vessel, whose suspicious activities had been on our radar in the western Indian Ocean circuit.”

Brigadier Kiswaa echoed the sentiment.

“We have succeeded due to cooperation from regional partners who have been working closely with us. The vessel was on the radar of the international community,” he explained.

Behind that diplomatic language lies a sophisticated surveillance and intelligence network that spans continents, involves satellite tracking, signals intelligence, human sources, and the kind of patient police work that builds cases one piece of evidence at a time.

The operation also demonstrates Kenya’s commitment to securing its territorial waters and combating transnational organized crime.

President William Ruto’s administration has made noise about cracking down on corruption and insecurity. Operations like this give substance to the rhetoric.

The Questions That Keep Investigators Awake

But questions remain, and they are the kind that will drive investigators to work late nights for months to come.

Who owns MV Igol?

Shell companies within shell companies, most likely, registered in jurisdictions that ask no questions and keep no records.

Where was the methamphetamine manufactured? Iran? Pakistan? Myanmar? Afghanistan? China? The precursor chemicals could have come from anywhere, the lab could have been operating in any number of countries where governance is weak and enforcement is weaker.

What was the intended destination? Amin said it was destined for local markets, but which local markets? Kenya? Tanzania? Uganda? South Africa? Europe via a circuitous route? Who were the buyers? Criminal syndicates operating in Nairobi’s slums? International cartels with reach across the continent? Terrorist groups looking to finance operations through drug sales? The possibilities are endless and terrifying.

How many other vessels are currently plying these waters with similar cargo? For every ship intercepted, how many slip through? The Indian Ocean is vast, surveillance resources are limited, and traffickers are adaptive.

This seizure, as significant as it is, represents only what was caught.

The unknown quantity of drugs that successfully made landfall is what should keep policymakers awake at night.

During the inspection at Mombasa port, some foreigners, their identities carefully undisclosed, were observed taking photographs and weighing small packages.

Were these law enforcement officials from partner nations, collecting evidence for parallel investigations? Intelligence operatives tracking the broader network? Or representatives of other interested parties whose involvement in the drug war operates in shadows? The opaque nature of international drug interdiction means the public may never know, and perhaps that is by design.

The Reckoning: Victory and Warning

As the six Iranians sit in detention awaiting their Monday court appearance, and as investigators sift through evidence, conduct forensic analysis, and build the prosecutorial case that will hopefully see these men convicted and imprisoned, one thing is clear: Sh8.2 billion worth of methamphetamine will not flood Kenyan streets, will not destroy Kenyan families, will not fund criminal enterprises that thrive on human misery, will not corrupt additional officials, will not finance terrorism or organized crime.

This is a victory, and it deserves to be celebrated. The men and women who pulled off this operation worked long hours, took risks, and demonstrated the professionalism that Kenya’s security services are capable of when adequately resourced and properly led.

But it is also a warning.

For every vessel intercepted, how many slip through? For every kilogram seized, how much reaches its destination? The drug war is not won with individual busts, no matter how spectacular. It is won with sustained pressure, international cooperation, robust legal frameworks, judicial systems that actually convict traffickers instead of letting them walk on technicalities, and domestic resolve to address the demand that makes trafficking profitable in the first place.

Kenya has a drug problem.

It is not as severe as some countries, but it is growing. Methamphetamine use is increasing, particularly in urban areas where poverty, unemployment, and hopelessness create fertile ground for addiction.

Cocaine and heroin transit through Kenyan ports regularly.

Marijuana cultivation is widespread. Prescription drug abuse is rising.

The demand side of the equation needs as much attention as the supply side, but demand reduction requires investment in treatment, education, economic opportunity, and hope. Those are harder to fund and politically less sexy than drug busts with billion-shilling price tags.

The Iranians will have their day in court. The methamphetamine will be destroyed, probably burned in an incinerator under guard, its toxic fumes rising into the Mombasa sky like an offering to the gods of law enforcement.

MV Igol will rust in impound, its hull eventually cut up for scrap, its identity erased from shipping registries.

But somewhere in the Indian Ocean, right now, another vessel is making its way toward another coast, carrying another cargo, crewed by other desperate or greedy men, chasing another billion-shilling payday.

The economics of the drug trade are too lucrative, the risks too manageable, the demand too persistent for this to be the last ghost ship Kenya intercepts.

The question is not whether another will come.

The question is whether Kenya’s security apparatus will be ready, whether the multi-agency cooperation that made this operation successful can be sustained, whether the international partnerships that provided the intelligence will continue to bear fruit, and whether Kenya will invest in the long-term solutions that actually reduce drug demand rather than just interdicting supply.

The fight against drugs is a marathon, not a sprint. Kenya won this round. The war continues.

Some of the 1024 kilograms of synthetic drugs seized from six Iranian crew members aboard an Iranian Vessel worth Sh8.2billion some 650 km off the shore of Mombasa.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Development4 days ago

Development4 days agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoHow Close Ruto Allies Make Billions From Affordable Housing Deals

-

Entertainment2 weeks ago

Entertainment2 weeks agoKRA Comes for Kenyan Prince After He Casually Counted Millions on Camera

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoAmerican Investor Claims He Was Scammed Sh225 Million in 88 Nairobi Real Estate Deal

-

Investigations1 week ago

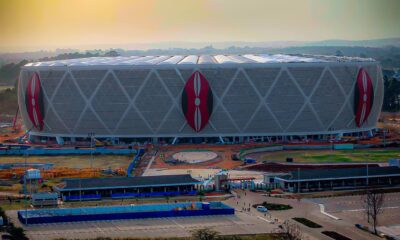

Investigations1 week agoTalanta Stadium Construction Cost Inflated By Sh11 Billion, Audit Reveals