Africa

The Rise of Bol Mel: Sanctioned South Sudanese Tycoon Who Could Inherit Kiir’s Presidency

For a country already grappling with economic crisis, humanitarian challenges, and weak institutions, the elevation of a figure under active corruption sanctions represents a particularly troubling development.

How a US-sanctioned businessman has maneuvered into position to potentially lead one of Africa’s most troubled nations

JUBA, South Sudan — In the labyrinthine corridors of South Sudan’s political establishment, few ascents have been as meteoric—or as controversial—as that of Dr. Benjamin Bol Mel. Once a businessman operating in the shadows of President Salva Kiir’s inner circle, Mel has emerged as the regime’s heir apparent despite being under active US sanctions for corruption since 2017.

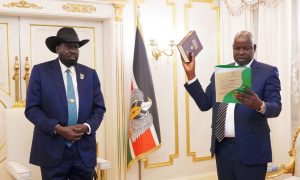

The latest chapter in this remarkable political transformation unfolded this week when President Kiir appointed Mel as First Vice Chairperson of the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), positioning him directly in line for the presidency according to the country’s transitional arrangements.

Mel’s journey to the apex of South Sudanese power began in the commercial sector, where he built a business empire centered around road construction and government contracts.

His companies including the now-sanctioned ABMC Thai-South Sudan Construction Company and Home and Away Ltd secured lucrative deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars, often without competitive bidding processes.

The businessman’s proximity to President Kiir proved invaluable. Serving as Kiir’s principal financial advisor and later as Presidential Envoy on Special Programmes, Mel cultivated relationships that would later translate into political capital.

His appointment as Vice President for the Economic Cluster in February 2025, replacing long-time Kiir ally James Wani Igga, marked his formal entry into the highest echelons of government.

But it was Tuesday’s announcement that truly signaled Mel’s ascendancy.

By naming him First Vice Chairperson of the SPLM, Kiir has effectively positioned his protégé as his potential successor, should the presidency become vacant during the current transitional period.

The Sanctions Shadow

Mel’s rise occurs under the long shadow of US sanctions imposed during the first Trump administration in December 2017.

The Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated Mel and several of his companies under the Global Magnitsky Act, citing their involvement in corruption schemes that diverted public resources for personal gain.

The sanctions were renewed in April 2025, with OFAC maintaining that Mel continues to pose risks to South Sudan’s financial integrity.

According to US authorities, his network of companies received over $3.5 billion in no-bid government contracts, including questionable deals for road construction projects that vastly exceeded standard costs.

Perhaps most damaging are allegations that Mel operated under the alias “Kuol Akol Wieu” to obscure his business dealings.

Investigative reports suggest this false identity was used to register companies and secure contracts while evading scrutiny, a practice that has drawn sharp criticism from anti-corruption advocates.

The South Sudan Anti-Corruption Commission itself has reportedly been blocked from investigating Mel’s activities, with Commission Chairperson Ngor Kolong Ngor revealing that his agency discovered a UAE bank account linked to Mel containing $457.2 million, but was ordered not to pursue the matter.

Constitutional and international implications

Mel’s elevation raises serious questions about South Sudan’s commitment to good governance and transparency.

His appointment appears to violate multiple provisions of the country’s Transitional Constitution, including Article 121(2), which prohibits public officials from engaging in private business activities.

More broadly, his rise to power puts South Sudan at odds with international anti-corruption frameworks.

The country is signatory to both the UN Convention Against Corruption and the African Union Anti-Corruption Convention, both of which require the exclusion of officials credibly implicated in graft.

The financial implications extend beyond symbolic concerns.

As a designated person under US sanctions, any dollar-based transactions involving Mel carry legal risks for international partners.

This reality threatens to complicate South Sudan’s relationships with international financial institutions, donors, and correspondent banks, potentially triggering a cascade of economic consequences for the oil-dependent nation.

The appointment comes at a particularly sensitive moment for South Sudan’s international relationships.

The country remains on the Financial Action Task Force’s grey list for money laundering risks, and has missed key reform benchmarks that would improve its financial credibility.

Meanwhile, South Sudan’s oil revenues—the government’s primary source of income—are already heavily mortgaged through a controversial $13 billion loan agreement with a UAE shell company that has pledged the country’s crude exports until 2042.

UN experts have flagged this deal as potentially corrupt, with some reports suggesting Mel’s involvement.

The US Embassy in Juba has already expressed concern about the promotion of sanctioned individuals to senior government positions, warning that such moves could further strain bilateral relations.

A planned South Sudanese delegation to Washington faces the challenging task of addressing not only visa disputes and deportation issues, but also US concerns about the elevation of sanctioned figures to positions of influence.

The succession question

While President Kiir has given no indication of retirement plans, political observers increasingly view Mel’s appointments as laying groundwork for an eventual transition.

Under Article 1.6.5 of the 2018 peace agreement, should the presidency become vacant, the replacement would be nominated by the top leadership body of the ruling party—a position Mel now holds as First Vice Chairperson.

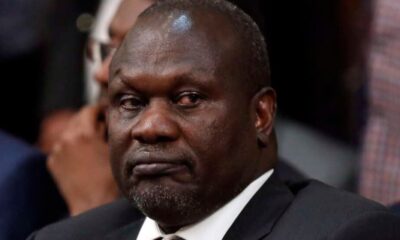

This succession planning occurs against the backdrop of ongoing tensions with First Vice President Riek Machar, who remains under house arrest following clashes in Upper Nile state.

Some of Kiir’s allies have suggested that the peace process can continue without Machar, potentially clearing the path for alternative succession arrangements.

The 2018 peace agreement contains provisions that could theoretically bar both Kiir and Machar from future elections, given their citation by a 2015 commission for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

However, the hybrid court meant to adjudicate such matters has never been established, leaving these restrictions largely theoretical.

Mel’s ascent represents more than individual ambition—it signals a fundamental transformation in the nature of the South Sudanese state.

What began as a post-conflict nation struggling toward democratic governance increasingly resembles what critics describe as a “criminal enterprise with a seat at the UN.”

The integration of a sanctioned individual into the highest levels of government sends a stark message about the regime’s priorities and its relationship with international norms.

For a country already grappling with economic crisis, humanitarian challenges, and weak institutions, the elevation of a figure under active corruption sanctions represents a particularly troubling development.

Civil society groups have warned that Mel’s appointment marks “South Sudan’s final descent into kleptocracy,” arguing that his control over economic policy could institutionalize corruption at unprecedented levels.

The Reclaim Campaign, a South Sudanese civil society coalition, has characterized the move as crossing a “dangerous threshold” that transforms the country from a fragile post-conflict state into something far more problematic.

As South Sudan approaches scheduled elections in December 2026, Mel’s positioning raises fundamental questions about the country’s trajectory.

His rise illustrates how individuals can leverage proximity to power and control over resources to achieve political prominence, even while under international sanctions.

The international community faces difficult choices in responding to these developments.

Continued engagement risks legitimizing a regime increasingly dominated by sanctioned individuals, while isolation could further destabilize an already fragile state with significant humanitarian needs.

For South Sudan’s 12 million citizens, Mel’s ascent represents both continuity and change—continuity in the dominance of a small elite over the country’s resources, and change in the brazenness with which such dominance is now exercised.

Whether this trajectory can be altered, or whether it represents South Sudan’s new normal, may well determine the country’s future for decades to come.

The rise of Benjamin Bol Mel thus stands as more than a political appointment—it represents a test case for international efforts to promote good governance in fragile states, and a stark reminder of how quickly democratic aspirations can give way to more troubling realities.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoEx-Inchcape Kenya CEO Sanjiv Shah Charged With Bank Fraud

-

Development1 week ago

Development1 week agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNIS Kismu Hotel Secret Tape That Sealed Gachagua’s Fate and MP Ng’eno Death in A Chopper Crash

-

Investigations1 day ago

Investigations1 day agoSOLD TO THE BULLET: How the Bodyguard Handed MP Ong’ondo Were to His Killers

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoInvestor Sued Over Sh30,000 Fee to Access Runda Road

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoDid Festus Omwamba Take the Fall? The Puzzle of a Senator’s Ouster and a Call to the CS

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoI Swore Never To Hire The Chopper Again, Author Recalls Harrowing Experience in Helicopter That Killed MP Ng’eno Alleges Poor Maintenance By Owners

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoRevealed: Ex-VP Moody Awori Has Never Received Pension Benefits Since His Retirement in 2007