Sci & Tech

The Astonishing Migration Of ‘American TikTok Refugees’ To A Chinese App They Knew Nothing About

In just 48 hours, Xiaohongshu gained 700,000 users. While, for the past two decades, China has progressively blocked all foreign social media, creating a censored internet bubble inside a “great digital wall,” the Chinese are waking up.

Users – mostly women – share videos and photos of their vacations, make-up, clothing choices, pets and restaurants. The lifestyle app is intended for a Chinese audience only and only exists in Chinese. However, since Monday, January 13, it has been the most downloaded iPhone app in the United States, ahead of another previously little-known Chinese social media application, Lemon8, developed by Tiktok’s parent company.

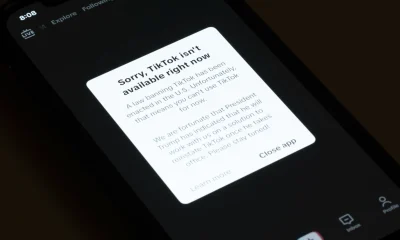

The administration of US President Joe Biden considers that by harvesting the data of its 170 million US users, TikTok, an international version of a Chinese social media platform, constitutes a threat to national security. A law passed in April 2024 gives its owner, the Bytedance group, until this Sunday to give it up. It will otherwise no longer be possible to download it in the US, and risks becoming obsolete.

Good-natured interactions

Now, a single theme dominates Xiaohongshu: “TikTok refugees,” i.e. all those new profiles of Americans who have managed to register with the help of Google Translate, and who are arriving in the run-up to January 19. In just 48 hours, Xiaohongshu gained 700,000 users. While, for the past two decades, China has progressively blocked all foreign social media, creating a censored internet bubble inside a “great digital wall,” the Chinese are waking up. They are astonished to see these citizens of the world’s leading power, with whom relations are so strained, arriving on their app. “Did I come to the wrong place? It’s all in English,” said Tan Ming, originally from Sichuan province.

Interactions are generally good-natured, especially as both Chinese citizens and American newcomers share a critical view of the Biden administration. When it comes to exposing their data, many admit to going in blind. “I trusted the terms and conditions more than any American application. Even if I didn’t understand anything,” said an app newbie, in one of their posts. Parker, a young blonde in a cowboy hat and denim overalls, danced to a folk tune. She wrote alongside: “Hey TikTok alumni, I’m trying to transfer my stuff.” To which a user named H., in Tianjin in northeast China, responded, with a dash of humor, “Welcome to the spies’ place, give me your data.”

Having discovered the 100% Chinese internet, many people say they are totally lost. In a video, a Westerner but apparently already experienced Xiaohongshu user, Yana Kim, offered her advice in this highly censored environment. “China is very conservative. They control social media very strictly. There’s a big difference with social media in the West. You have to be careful what you say, what you wear, what you post,” she said. “In China, there are sensitive words. Avoid saying what’s not allowed,” added an internet user from Guangdong province, who describes himself as a “cultural guide.”

Moderation in English

Megaroo8, an American, who created his account on Tuesday, said: “Is there a lot of censorship here? We’re told that Chinese media are censored, but people seem to be fine here.” To which a Chinese man took the liberty of replying that all he has to do is search for forbidden subjects in the country to experience having his account blocked. He told Megaroo8 that “most internet users have naturally developed a sense of renunciation to sensitive subjects.” Still, a newcomer tried to find out if it was acceptable to ask if the laws are different between China and Hong Kong. A Chinese man replied, “We’d rather not talk about that here.”

In any case, most of them didn’t come to criticize the Chinese government or ask about freedom of expression issues. In contrast, topics critical of American society are flourishing. One Chinese internet user, Ermazi, wanted to know “if there really are homeless people all over the United States,” as the Chinese press often suggests. Another asked if it was true that there are “killings everywhere in the United States, as the Chinese news says.” One internet user took the liberty of telling an American doctoral student in political science that “it’s American politics that’s the problem.”

The influx of users took the platform’s management by surprise. At a time when Chinese websites are having to block forbidden topics with the utmost zeal in order to continue to be tolerated by Beijing, Reuters reports that the platform is in a hurry to develop its English-language content moderation.

Meanwhile, a Californian “Tiktok refugee” by the name of Jose Carlo Hernandez Orozco, who thought he was contributing to the dialogue of civilizations by writing “You can ask me anything,” found himself bombarded with English homework assignments sent by young Chinese students.

(Le Monde)

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoEastleigh Businessman Accused of Sh296 Million Theft, Money Laundering Scandal

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoInside Nairobi Firm Used To Launder Millions From Minnesota Sh39 Billion Fraud

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoMost Safaricom Customers Feel They’re Being Conned By Their Billing System

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoUnfit for Office: The Damning Case Against NCA Boss Maurice Akech as Bodies Pile Up

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoEXPLOSIVE: BBS Mall Owner Wants Gachagua Reprimanded After Linking Him To Money Laundering, Minnesota Fraud

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTax Payers Could Lose Millions in KWS Sh710 Insurance Tender Scam As Rot in The Agency Gets Exposed Further

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPastor James Irungu Collapses After 79 Hours Into 80-Hour Tree-Hugging Challenge, Rushed to Hospital

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoDeath Traps: Nairobi Sitting on a Time Bomb as 85 Per Cent of Buildings Risk Collapse