Business

Questions as Deported Turkish Businessman Allied to Ruto Pursues Solar Power Deal

Aydin has since been linked to significant government contracts, including participation in Kenya’s affordable housing program through his company MHOA Africa Limited, which is part of a joint venture tasked with building over 100,000 homes.

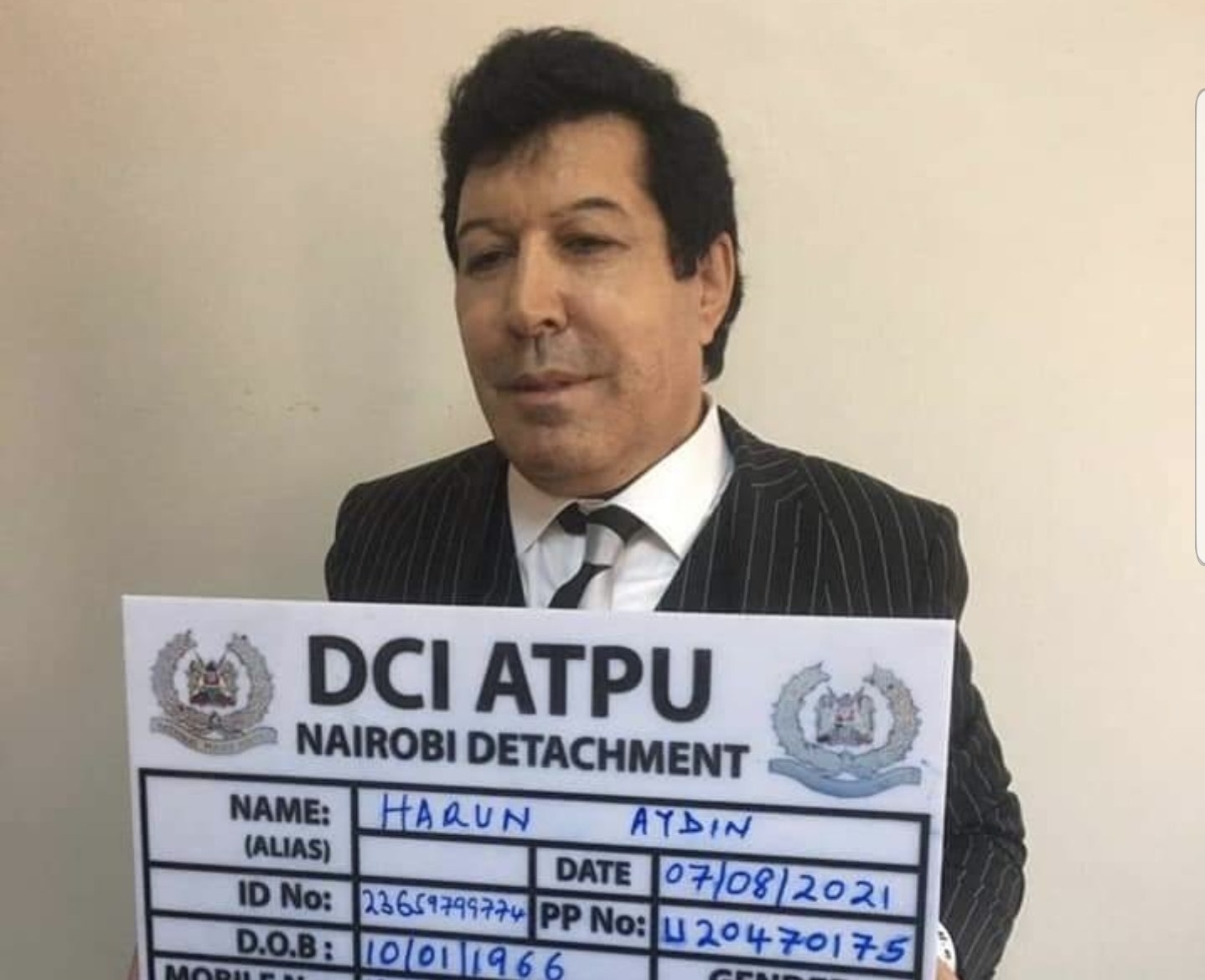

A controversial solar power project linked to Harun Aydin, the Turkish businessman who was deported from Kenya in 2021 but maintains close ties to President William Ruto, is raising serious questions about transparency and due diligence in the country’s renewable energy sector.

Unit 2HA Investment Energy Africa, a company where Aydin is listed as director and shareholder, has secured environmental approval to develop a 50-megawatt solar plant in Laikipia County despite glaring inconsistencies in its project proposal.

The firm’s estimated budget of Sh155.47 million for the project appears woefully inadequate, representing less than three percent of what similar projects typically cost.

Industry standards suggest that solar plants cost approximately $1 million per megawatt to construct, which would put Aydin’s project at around Sh6.4 billion rather than the declared Sh155 million.

This massive discrepancy becomes even more puzzling when compared to other solar initiatives in Kenya, where 40MW plants have required budgets exceeding Sh6 billion.

The project’s land requirements also defy conventional wisdom. While most solar installations in Kenya operate on 300 to 600 acres, Aydin’s venture proposes using 3,000 acres for a 50MW plant.

A cancelled project of similar scope in the same Rumuruti location was planned for just 300 acres at a cost of Sh6.7 billion.

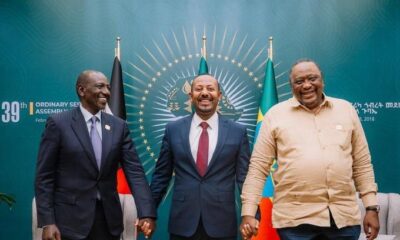

Aydin’s return to prominence in Kenya’s business landscape marks a remarkable rehabilitation for someone who was detained and deported over allegations of terrorism financing and money laundering.

His deportation came during a period of political tension between then-President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto, with the Turkish businessman caught in the crossfire of their deteriorating relationship.

The businessman’s fortunes changed dramatically following Ruto’s ascension to the presidency in August 2022.

Aydin has since been linked to significant government contracts, including participation in Kenya’s affordable housing program through his company MHOA Africa Limited, which is part of a joint venture tasked with building over 100,000 homes.

What makes the solar project particularly concerning is the apparent disconnect between regulatory oversight and project implementation.

While the National Environment Management Authority has approved the project, the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority confirmed it has yet to receive any permit application from the company.

The timing and circumstances surrounding this project highlight broader questions about governance and the influence of personal relationships in awarding government contracts.

Aydin’s presence at State House functions and his companies’ success in securing major deals despite his controversial past suggests a level of access that bypasses normal vetting processes.

Kenya’s push toward renewable energy is commendable, with solar power currently contributing 3.6 percent of the country’s electricity generation.

However, the integrity of this transition depends on transparent procurement processes and realistic project proposals that can actually deliver the promised outcomes.

As the country grapples with energy security and the need for sustainable power generation, projects like Aydin’s solar venture serve as a test case for whether Kenya can balance its development needs with proper governance standards.

The discrepancies in this proposal demand thorough investigation before any further approvals are granted.

The energy sector’s credibility hinges on ensuring that all players, regardless of their political connections, meet the same rigorous standards for project viability and transparency.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoAlleged Male Lover Claims His Life Is in Danger, Leaks Screenshots and Private Videos Linking SportPesa CEO Ronald Karauri

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoRussian Man’s Secret Sex Recordings Ignite Fury as Questions Mount Over Consent and Easy Pick-Ups in Nairobi

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Investigations7 days ago

Investigations7 days agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy

-

Economy6 days ago

Economy6 days agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Africa1 week ago

Africa1 week agoFBI Investigates Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s Husband’s Sh3.8 Billion Businesses in Kenya, Somalia and Dubai

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoM-Gas Pursues Carbon Credit Billions as Koko Networks Wreckage Exposes Market’s Dark Underbelly