Investigations

Meth Is Replacing Older Drugs As Kenya Becomes Major Hub For Drug Trafficking In The Region

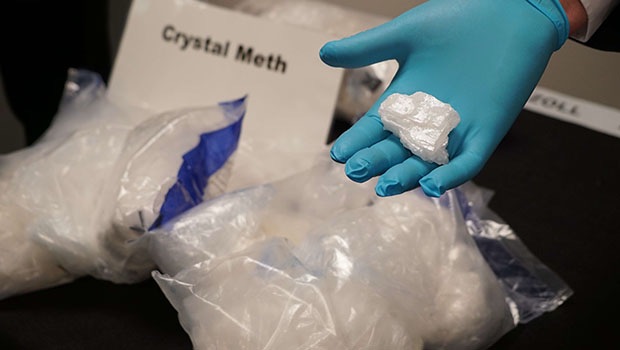

This cheaper, more intense substitute for crack cocaine has established consumer bases in informal settlements across Nairobi, Kisumu, and Mombasa.

Investigation reveals how Kenya has transformed from transit route to manufacturing powerhouse in continent’s illicit drug economy

Kenya has evolved from a peripheral player to a central hub in Africa’s rapidly expanding illicit drug economy.

What began as simple transit routes for cocaine and heroin has transformed into a sophisticated narcotics powerhouse featuring industrial-scale methamphetamine production, extensive cannabis cultivation networks, and the emerging specter of synthetic opioids flooding regional markets.

New findings from the Eastern and Southern Africa Commission on Drugs (ESACD) paint a stark picture of Kenya’s metamorphosis into a drug trafficking epicenter, with methamphetamine leading a synthetic revolution that is systematically displacing traditional narcotics across the region.

The synthetic takeover

Methamphetamine has emerged as the defining threat of Kenya’s drug crisis. Once considered a localized problem confined to South Africa, “crystal meth” has taken root in Kenya’s criminal underworld over the past five years, establishing the country as a key node in a manufacturing corridor stretching from South Africa through Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

The ESACD report reveals that methamphetamine is rapidly displacing crack cocaine as the preferred illicit stimulant across multiple communities.

“It is becoming the dominant substance used in a growing number of communities where it has displaced crack cocaine as the illicit stimulant of choice,” the commission found.

This cheaper, more intense substitute for crack cocaine has established consumer bases in informal settlements across Nairobi, Kisumu, and Mombasa.

The drug’s appeal lies in its accessibility offering a more powerful high at a fraction of the cost of traditional stimulants.

Clandestine laboratories, suspected to operate in Nairobi’s industrial zones and coastal hideouts, represent a new level of criminal sophistication.

These facilities are part of a broader regional manufacturing network that has transformed Kenya from a mere transit point into a production center.

The precursor pipeline

The mechanics of Kenya’s meth production reveal a complex international supply chain. Evidence points to increased flows of precursor chemicals including ephedrine and red phosphorus from India and China, often arriving in disguised shipments through Mombasa Port or Nairobi’s air freight terminals.

Nigerian supply networks have emerged as dominant players in this trade, controlling what has become a continent-wide methamphetamine economy.

Since 2016, both the purity and availability of methamphetamine in Eastern and Southern Africa have increased dramatically, with Kenya serving as a crucial transit hub feeding inland markets in Uganda, Zambia, and the Great Lakes region.

The March 2025 discovery of a sophisticated methamphetamine laboratory in Olelopo village, Namanga, demonstrated the international scope of these operations.

Operated by Mexico’s Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) and fronted as a poultry plant, the facility represented the first confirmed large-scale operation by a Mexican cartel in East Africa a development that underscores how global criminal networks now view Kenya as strategic territory.

The synthetic Opioid menace

Perhaps most ominous is the rising presence of synthetic opioids in the regional drug market.

While Kenya has so far avoided the type of fentanyl-led overdose epidemic that has devastated North America, regional forensic laboratories have begun detecting nitazenes a family of powerful synthetic opioids from China in neighboring island states.

In 2024, South Africa reported its first verified case of fentanyl presence in heroin street samples, a development that sent shockwaves through regional health authorities.

Kenyan heroin markets, already under strain from disruptions in Afghan production following the Taliban takeover, now risk contamination with synthetic adulterants as traffickers scramble to maintain potency.

The implications are catastrophic.

Kenya’s heroin crisis, once confined to Mombasa’s beaches, now reaches into Nairobi’s alleyways and Kisumu’s lakeside corridors.

Injection drug use, a rarity two decades ago, now accounts for up to half of heroin consumption in certain communities—a shift that dramatically raises HIV and hepatitis transmission risks in a country with already overstretched public health systems.

A cannabis empire

While synthetic drugs capture headlines, cannabis remains Kenya’s most resilient and widespread drug crop.

Cultivated in every county, especially in inaccessible highland and forested areas, the plant has become both a subsistence crop and commercial product generating substantial illicit revenue.

Kenya, alongside Uganda, Malawi, and Tanzania, is classified as a regional supply pillar in what has become a self-sustaining cannabis economy.

Despite continuous eradication campaigns, enforcement success remains marginal cultivation often thrives just kilometers from law enforcement posts.

The cannabis trade has evolved beyond traditional boundaries.

Kenyan-grown cannabis now supplies not only regional markets but also feeds European demand through sophisticated trafficking networks.

As South Africa moves toward cannabis legalization for medical and recreational use, pressure is mounting on Kenya to revise its own policies—a shift that could fundamentally disrupt both illicit and semi-licit cultivation zones.

Cocaine’s persistent presence

Kenya’s role in the global cocaine trade has also evolved significantly.

While most shipments historically transited through the Port of Mombasa en route to Europe and Asia, a growing portion now remains in domestic markets.

The trafficking methods have diversified beyond maritime routes to include air cargo, tourist luggage, and overland trucking networks.

The domestic cocaine market reflects broader socioeconomic divisions. Crack cocaine has overtaken powder as the stimulant of choice among lower-income consumers in Nairobi and Kisumu, while affluent urban circles have become key powder cocaine markets, fueling nightlife economies and drawing traffickers deeper into the social fabric.

This market stratification with crack serving the poor and powder cocaine catering to the wealthy illustrates how drug trafficking both exploits and reinforces existing inequalities.

The infrastructure of corruption

Kenya’s transformation into a drug trafficking powerhouse didn’t occur in a vacuum.

The country’s position as a coastal state with sophisticated logistics infrastructure, combined with corrupt government agencies, has allowed traffickers to embed narcotics flows into commercial routes with remarkable success.

The corruption extends beyond simple bribery. Traffickers have systematically infiltrated legitimate business sectors, using front companies, corrupted officials, and compromised supply chains to move vast quantities of drugs with minimal detection risk.

The ESACD report draws a direct connection between drug proliferation and failed development policies.

“The growth in the use of synthetic drugs such as methamphetamine can be seen as a consequence of the region’s urban development inadequacies,” the commission notes.

The drug epidemic is “quickly occupying the deteriorating spaces of the growing number of marginalized and victimized communities facing limited opportunities for licit socio-economic prosperity.”

This analysis reveals how narcotics fill voids left by inadequate urban planning, deepening inequality, and vanishing economic opportunities.

Secondary and tertiary towns now host vibrant retail drug markets, particularly for heroin and crack cocaine.

Poly-drug use has become the norm, while injection drug use, with its links to HIV and hepatitis C transmission, has permeated the entire region.

Recent statistics from Kenya’s Ministry of Health reveal that over half of the country’s drug users are under 35 years old, a demographic shift that threatens to reshape entire communities for generations.

The National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse identifies friends as the primary drug source, accounting for 66.4% of distribution, highlighting how peer networks accelerate substance abuse among young people.

Despite the escalating crisis, regional governments continue relying on outdated enforcement strategies that the ESACD characterizes as both “ineffective and harmful.”

The focus on arresting smallholder cannabis farmers and low-level drug peddlers has resulted in prison overcrowding, with some facilities holding more than 250% of their capacity.

This approach creates a destructive cycle. Large numbers of economically disadvantaged individuals are incarcerated for non-violent drug offenses, then face “long-term stigma and limited job prospects” upon release.

The result is “disproportionately high unemployment and underemployment rates” among former drug users, particularly those “marginalized by criminal convictions for low-level drug offences.”

Data deficit crisis

Perhaps most concerning is the information void that hampers effective responses. “In most countries of the region, there is no reliable determination of some of the basic marketplace denominators needed to assess a drug market, the harms it is creating or the relative effectiveness of measures put in place to address these,” the ESACD report warns.

“In the absence of such basic information, it is not possible to mount an effective national response to illicit drug markets or to measure the effects of such a response.”

This data deficit leaves policymakers operating blind, unable to design evidence-based interventions or measure program effectiveness.

Without reliable information on market size, user demographics, consumption patterns, and health impacts, governments are essentially fighting an invisible enemy.

Kenya’s transformation has regional implications that extend far beyond its borders.

The country now serves as a critical node in continental trafficking networks, with synthetic drugs manufactured in Kenyan facilities spreading across East Africa.

The methamphetamine produced in Kenya feeds markets in Uganda, Zambia, and throughout the Great Lakes region.

The ESACD warns that methamphetamine’s reach will continue expanding: “It is inevitable that meth will penetrate every other drug market in the region, and its availability, accessibility, and use will increase.”

International criminal networks

The presence of Mexican cartels in Kenya represents a new phase in the country’s drug evolution.

The Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generación’s Namanga operation, though shut down in September 2024 based on U.S. intelligence, demonstrated how international criminal organizations now view East Africa as strategic territory worth significant investment.

These international partnerships bring sophisticated production techniques, established smuggling routes, and vast financial resources that local law enforcement agencies are ill-equipped to combat.

The cartels’ ability to operate clandestinely, using Kenyan nationals to purchase land and establish legitimate business fronts, reveals a level of operational sophistication that traditional policing methods cannot address.

The ESACD report proposes comprehensive reforms including reliable drug data collection, harm-reduction policies, and socioeconomic reintegration programs for offenders.

However, implementation faces significant obstacles including limited resources, institutional corruption, and political resistance to evidence-based approaches.

With synthetic opioids now emerging and methamphetamine production scaling up, the window for effective intervention is rapidly closing. The commission’s warning is unambiguous: Kenya’s role in the continent’s drug economy is “no longer peripheral.”

A continental crisis

Kenya’s evolution from drug transit route to trafficking powerhouse reflects broader failures in development, governance, and regional security cooperation. As methamphetamine displaces traditional drugs and international criminal networks establish permanent operations, the country faces a crisis that transcends law enforcement.

The synthetic revolution now sweeping across Kenya and the broader region represents more than a criminal justice challenge—it’s a symptom of systemic inequalities, failed urban development, and the inability of legitimate economies to provide opportunities for marginalized communities.

The choice facing Kenyan leadership is stark: continue with failed criminalization strategies that have produced mass incarceration without reducing drug availability, or embrace evidence-based approaches that address root causes while reducing harm. The cost of inaction—measured in destroyed lives, corrupted institutions, and destabilized communities—grows with each passing day.

As Kenya solidifies its position as a regional drug trafficking hub, the methamphetamine epidemic represents both an immediate crisis and a generational threat. Whether the country can extract itself from this trajectory will determine not only the fate of millions of its citizens but the stability of an entire region.

The transformation is complete: Kenya is no longer just a pathway for drugs—it has become a destination, a producer, and a regional command center in Africa’s evolving narcotics economy.

—–

About This Investigation

This report is based on findings from the Eastern and Southern Africa Commission on Drugs (ESACD), Kenya’s Ministry of Health data, reports from the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (NACADA), and includes the September 2024 Namanga laboratory bust involving the Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generación. Additional reporting incorporates evidence of precursor chemical flows from India and China through Mombasa Port.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Development4 days ago

Development4 days agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoHow Close Ruto Allies Make Billions From Affordable Housing Deals

-

Entertainment2 weeks ago

Entertainment2 weeks agoKRA Comes for Kenyan Prince After He Casually Counted Millions on Camera

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoAmerican Investor Claims He Was Scammed Sh225 Million in 88 Nairobi Real Estate Deal

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoTalanta Stadium Construction Cost Inflated By Sh11 Billion, Audit Reveals