Business

M-Gas Pursues Carbon Credit Billions as Koko Networks Wreckage Exposes Market’s Dark Underbelly

Circle Gas has already received $8.5m of a $27m carbon credit purchase offer, according to UK financial disclosures.

Circle Gas eyes $27m from controversial offset scheme while critics allege predecessor’s collapse stemmed from systematic overcrediting and regulatory defiance

Circle Gas, the London-listed parent company of Kenyan cooking gas distributor M-Gas, is pressing ahead with plans to extract more than $27m from carbon credit sales by June, even as the spectacular implosion of rival Koko Networks has laid bare endemic flaws in how the clean cooking sector monetises environmental claims.

The timing is striking. Just days after Koko Networks filed for bankruptcy on January 30, leaving 1.5 million households without subsidised bioethanol fuel and 700 employees jobless, M-Gas secured a Letter of Approval from Kenya’s National Environment Management Authority.

The company is now negotiating to upgrade these credits into the Paris Agreement’s Letter of Authorisation category, which would unlock access to higher-value international compliance markets.

But the wreckage of Koko Networks, which invested $300m before collapsing in a dispute with Kenyan regulators, has exposed troubling questions about whether companies in this sector are generating genuine climate benefits or merely exploiting loopholes in carbon accounting rules to manufacture phantom emission reductions.

According to a detailed analysis circulating among carbon market participants, Koko’s business model was fundamentally compromised by three critical flaws.

The company claimed a 93 per cent fraction of non-renewable biomass rate for Nairobi, when scientific studies show the actual figure is closer to 38 per cent.

This single metric, which measures the rate at which trees fail to regenerate after being harvested for charcoal, resulted in Koko overclaiming its climate impact by 2.4 times.

The overcrediting extended further. Koko asserted that all 1.3 million customers previously used only charcoal, despite Kenya’s 2019 census showing 67.2 per cent of Nairobi households already used liquefied petroleum gas.

The company then compounded these distortions by claiming customers consumed 15 litres of bioethanol monthly, based on surveys of just 159 households out of 900,000, rather than using precise consumption data its automated fuel dispensers actually collected.

Independent ratings agency BeZero Carbon assigned Koko a B grade overall, indicating low likelihood of achieving claimed emission reductions, and a D rating specifically for carbon accounting.

When the Government of Kenya requested Koko amend its methodology to use accurate figures, the company refused, effectively choosing bankruptcy over compliance.

The Kenyan government has now publicly defended its decision to deny Koko authorisation.

Trade Cabinet Secretary Lee Kinyanjui revealed that Koko sought approval to sell carbon credits that would have exhausted Kenya’s entire allocation under the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 compliance market, effectively monopolising the country’s carbon export capacity.

“The business model did not align. It was not possible to allow everything they wanted to claim because it would mop up everything that Kenya would otherwise do,” Kinyanjui told reporters. “If we took up all the carbon credits that Kenya would get and gave only one company, what would we tell the 10 or 20 other companies that are also eligible for the same, including those in agriculture and manufacturing?”

The remarks offer the first detailed official explanation for Koko’s collapse and preview Kenya’s anticipated legal defence against potential claims.

Beyond the overcrediting concerns, Kinyanjui cited fundamental disagreements over credit volumes. “In the tabulation of numbers, there was no concurrence because if Kenya gave in and authorised the numbers they were claiming, no other company in Kenya would have been able to claim.”

Kenya also questioned the authenticity of Koko’s carbon credits and cited lack of transparency in the firm’s business model.

While acknowledging Koko’s important role in reducing reliance on charcoal, Kinyanjui insisted the company’s approach was fundamentally flawed.

“When the business model is not workable, even if you push the journey at some point it will stall. What the company needs is a rethink and to reconfigure its business model.”

M-Gas now enters this fraught landscape with structural advantages and vulnerabilities.

The company uses LPG rather than bioethanol, a fuel switch that BeZero research suggests produces up to six times fewer carbon dioxide emissions than biomass stoves.

Its smart meters, connected via Safaricom’s narrowband Internet of Things network, can theoretically provide the precise usage data that Koko conspicuously avoided reporting.

Yet M-Gas operates under similar economic constraints.

The company posted a $24.2m operating loss for 2024, down from $33.3m the previous year but still deeply in the red.

Like Koko, M-Gas provides cylinders and cookers at no upfront cost, subsidising both equipment and fuel prices through projected carbon revenues.

The business model remains fundamentally dependent on selling offsets at premium prices.

Circle Gas has already received $8.5m of a $27m carbon credit purchase offer, according to UK financial disclosures.

The company estimates that securing a Letter of Authorisation, which allows credits to be sold under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement with corresponding adjustments to Kenya’s national carbon accounts, could raise an additional $9m based on credits already issued.

Safaricom, Kenya’s dominant telecommunications provider, holds an 18.96 per cent stake in Circle Gas, with both current chief executive Peter Ndegwa and former chief Michael Joseph sitting on the UK firm’s board.

The Kenyan government owns 35 per cent of Safaricom, creating indirect state exposure to M-Gas’s carbon strategy.

The clean cooking carbon credit market has become a battleground between development imperatives and integrity concerns.

Research published by UC Berkeley in January 2024 found average overcrediting of 9.2 times across widely used methodologies, with worst cases exceeding 1,000 per cent overclaiming.

The study specifically identified the methodology Koko employed as particularly problematic.

Carbon standards bodies have responded. Gold Standard introduced new requirements in January 2026 mandating accurate fraction of non-renewable biomass calculations.

The sector’s new CLEAR methodology, developed by the Clean Cooking and Climate Consortium, promises continuously tracked energy consumption data.

Three methodologies from Verra and Gold Standard have earned Core Carbon Principles certification, signalling improved accounting practices.

These reforms come too late for Koko. David Ndii, economic adviser to President William Ruto, described the case as uniquely multidimensional, involving questions about the Paris Agreement itself, cookstove credit veracity, Kenya’s carbon regulations, Koko’s business model transparency, and diplomatic interference.

When asked about the $300m invested and jobs lost, Ndii replied curtly that even good doctors lose patients.

The Koko collapse also threatens Kenyan taxpayers with a potential $179.6m liability.

The World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency provided political risk insurance to Koko in March 2025, specifically covering the carbon credit programme against breaches like expropriation. Koko is now preparing to file a claim alleging the Kenyan government breached its obligations, potentially triggering the guarantee.

The insurance claim carries particular weight because Kenya had signed an investment framework agreement with Koko in June 2024 that appeared to clear the path for compliance market sales under Article 6.

However, the government never issued the letters of authorisation required to complete transactions, creating what Koko may argue constitutes a breach of contract.

The MIGA policy explicitly covers government breach of contract, and Kinyanjui’s public comments appear designed to establish that Kenya acted reasonably in protecting its limited carbon budget allocation.

PricewaterhouseCoopers assumed control of Koko on February 1 through administrators Muniu Thoithi and George Weru, raising faint hopes of a potential rescue.

But with the company having lost money on every litre of fuel sold to 1.5 million households and operating 3,000 bioethanol refilling machines across Kenya, any restructuring would require fundamentally reimagining a business model predicated on carbon revenues that proved unattainable.

M-Gas must navigate this treacherous terrain while Kenya’s regulators face pressure to both attract climate investment and ensure exported carbon credits represent genuine emission reductions that do not compromise the country’s Paris Agreement commitments.

Kenya has limited capacity to authorise carbon credit transfers without exhausting its nationally determined contribution budget.

The government’s stance reflects hard commercial realities. Compliance market credits fetch approximately $20 per tonne, roughly ten times the $1-$2 commanded by largely discredited voluntary market offsets.

Koko’s business model depended on accessing these premium prices, which its B-rated credits and questionable methodology made increasingly difficult.

The voluntary market prices proved insufficient to cover the company’s subsidies, which reduced fuel costs by 25-40 per cent and stove prices by up to 85 per cent.

M-Gas faces identical pressures. Its ethanol refills were priced from as low as 30 Kenyan shillings and stoves at approximately 1,500 shillings, making them cheaper than charcoal for poor households but creating the same dependency on carbon finance that destroyed Koko.

Unless M-Gas can demonstrate superior carbon accounting and secure higher ratings, it risks replicating Koko’s fatal trajectory.

The stakes extend beyond one country’s borders.

The aviation industry’s Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation faces a credit shortage ahead of crucial 2027-2028 compliance deadlines.

Airlines require millions of high-quality offsets, with prices in compliance markets reaching $20 per tonne compared with $1-$2 for standard credits in discredited voluntary markets.

BeZero analysis shows projects with AAA or AA ratings now command three times the price of lower-rated credits.

The market is bifurcating between developers that can prove their impact through metered data and those relying on sampling surveys prone to bias and manipulation.

For M-Gas, the path forward requires demonstrating it has learned from Koko’s mistakes.

The company must publish transparent, conservative carbon accounting that withstands academic scrutiny.

It must use precise consumption data its smart meters collect rather than convenient assumptions.

And it must price its service at levels that do not require perpetual carbon subsidies to remain viable.

The alternative is another spectacular failure that further erodes confidence in carbon markets, damages Kenya’s reputation as a destination for climate investment, and leaves hundreds of thousands of households cycling back to dirty cooking fuels that kill an estimated 15,000 Kenyans annually through indoor air pollution.

Circle Gas and M-Gas declined requests for comment on their carbon credit methodology and whether they plan to use accurate site-specific fraction of non-renewable biomass calculations rather than inflated national defaults.

The Kenyan government’s environment authority did not respond to questions about what standards M-Gas must meet to receive authorisation.

Kenya has established strict controls over carbon credit exports through a rigorous eligibility criterion administered by the National Environment Management Authority. NEMA issues letters of authorisation only after verifying that projects meet both domestic standards and requirements set by credit purchasers.

The dispute between NEMA and Koko centred on disagreement over authorised credit volumes, with the regulator refusing to approve quantities that would crowd out other eligible companies across agriculture, manufacturing and energy sectors.

The government now walks a delicate line.

Too restrictive, and it risks deterring the climate investment Kenya desperately needs to transition millions of households from deadly cooking fuels.

Too permissive, and it compromises the integrity of its carbon exports while potentially exhausting its Paris Agreement allowances on projects delivering questionable climate benefits.

Koko’s collapse suggests Kenya has chosen integrity over short-term investment, setting a precedent that will shape M-Gas’s negotiations.

What remains clear is that the clean cooking sector stands at an inflection point.

Carbon finance can either catalyse genuine transitions to cleaner energy or become another vehicle for greenwashing, where companies manufacture paper emission reductions while failing to deliver meaningful climate benefits.

Koko Networks chose one path and crashed. M-Gas must now choose its own.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Economy2 weeks ago

Economy2 weeks agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoKPC IPO Set To Flop Ahead Of Deadline, Here’s The Experts’ Take

-

Politics2 weeks ago

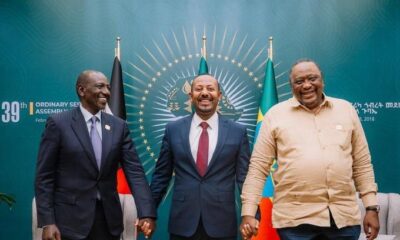

Politics2 weeks agoPresident Ruto and Uhuru Reportedly Gets In A Heated Argument In A Closed-Door Meeting With Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours