News

Kenyan Scientist Dr Arthur Obel Famed For Discovering AIDS ‘Cure’ Dies

Beyond his scientific pursuits, Prof Obel was known for his flamboyant lifestyle, owning a fleet of 21 luxury cars including Mercedes Benz and BMW models.

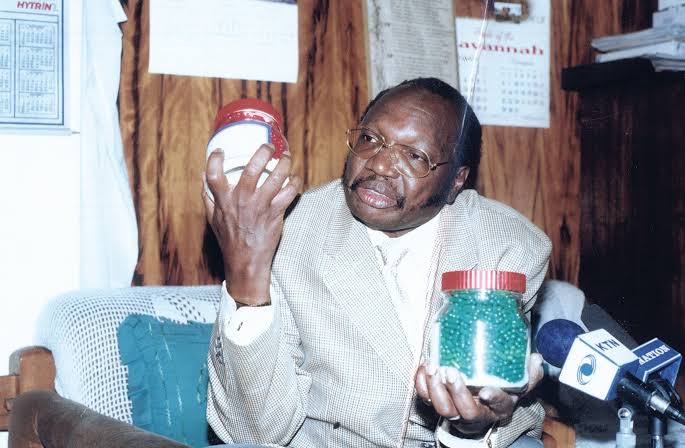

Professor Arthur Obel, the controversial Kenyan scientist who gained international attention for claiming to have discovered a cure for HIV/AIDS, has died aged 76 following a prolonged illness.

Prof Obel passed away on September 27, leaving behind a complex legacy that intertwined groundbreaking claims, scientific controversy, and an unapologetic pursuit of HIV treatment during the epidemic’s darkest years.

In 1990, Prof Obel, alongside former KEMRI director Dr Davy Koech, thrust Kenya into the global spotlight when they announced the discovery of Kemron, a drug they claimed could treat AIDS.

The announcement came at a time when HIV/AIDS was ravaging communities worldwide, with Kenya recording its first case in 1984.

According to the scientists, patients treated with Kemron showed remarkable improvement in symptoms and weight gain, with up to 10 percent reportedly showing no detectable HIV antibodies after treatment.

The drug, priced at Sh74 per tablet for a six-month course, generated unprecedented global demand from desperate patients seeking relief.

President Daniel arap Moi recognised the duo for bringing honour to Kenya, and the discovery sparked brief nationalistic euphoria.

However, the celebration was short-lived as international scientists challenged their claims, accusing them of fraud and noting the absence of controlled trials.

The World Health Organization discredited Kemron’s reliability, dismissing it as experimental.

More damaging revelations emerged when Weekly Review editor Hillary Ng’weno reported that the drug had originally been provided by American veterinary researcher Joseph Cummins for testing, with Obel and Koech later claiming credit for the discovery.

Undeterred by the controversy that forced even the Kenyan government to distance itself from Kemron, Prof Obel continued his research.

In the mid-1990s, he introduced Pearl Omega, priced at Sh30,000, followed by Iconaire in 2019, which he sold for the same amount while clarifying it was not a cure but could increase CD4 cell counts in HIV patients.

The medical establishment’s opposition to his work culminated in his deregistration by the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council, but Prof Obel remained defiant, insisting his primary concern was improving patients’ symptoms.

Beyond his scientific pursuits, Prof Obel was known for his flamboyant lifestyle, owning a fleet of 21 luxury cars including Mercedes Benz and BMW models.

In 2004, he faced legal troubles when charged with shooting at a matatu driver on Tom Mboya Street.

Found with a pistol and 19 bullets, he was fined Sh400,000 plus Sh100,000 in damages.

A father of three acknowledged children, Prof Obel never shied away from his reputation as a womaniser.

When questioned about his legendary appetite for women, he characteristically retorted: “Which man does not love women? Tell me, which man can say he does not love women?”

Despite spending a night in VIP police cells during his 2004 arrest, Prof Obel maintained his innocence in the shooting incident, claiming he had only drawn his weapon in self-defence when surrounded by hostile touts but never fired.

Prof Obel’s career embodied the tension between hope and scientific rigour during one of medicine’s most challenging periods.

While his claims were never validated through proper clinical trials, his work represented early African attempts at local solutions to a global health crisis that had stigmatised and devastated communities across the continent.

His legacy remains deeply contested – remembered by some as a visionary who offered hope when none existed, and by others as a cautionary tale about unverified medical claims.

What remains undisputed is his unwavering belief in his work and his refusal to be silenced by controversy.

Prof Obel’s death marks the end of an era for one of Kenya’s most polarising scientific figures, whose bold claims during the AIDS epidemic continue to spark debate about medical ethics, scientific validation, and the desperate search for cures during health crises.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTemporary Reprieve As Mohamed Jaffer Wins Mombasa Land Compensation Despite Losing LPG Monopoly and Bitter Fallout With Johos

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoPanic As Payless Africa Freezes With Billions of Customers Cash After Costly Jambopay Blunder

-

Investigations5 days ago

Investigations5 days agoFrom Daily Bribes to Billions Frozen: The Jambopay Empire Crumbles as CEO Danson Muchemi’s Scandal-Plagued Past Catches Up

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days ago1Win Games 2025: Ultimate Overview of Popular Casino, Sports & Live Games

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoSCANDAL: Cocoa Luxury Resort Manager Returns to Post After Alleged Sh28 Million Bribe Clears Sexual Harassment and Racism Claims

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow SportPesa Outfoxed Paul Ndung’u Of His Stakes With A Wrong Address Letter

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoHass Petroleum Empire Faces Collapse as Court Greenlights KSh 1.2 Billion Property Auction

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoShanta Gold’s Sh680 Billion Gold Discovery in Kakamega Becomes A Nightmare For Community With Deaths, Investors Scare