Opinion

Jowi! Why Raila’s Funeral Is The First of a Kind in Kenyan History

It was the first time the full apparatus of state honour was extended to someone who never held executive office.

The lakeside city of Kisumu stood still on that Saturday morning, its streets transformed into rivers of grief as tens of thousands poured out to bid farewell to their political colossus.

When the Kenya Air Force Leonardo C-27J Spartan, call sign Enigma01, descended through the early morning mist and touched down at Kisumu Airport at precisely 7:20am, two fire trucks released twin arcs of water over the aircraft in a ceremonial salute reserved for the most distinguished of the nation’s sons.

Inside that military craft lay the body of former Prime Minister Raila Amolo Odinga, draped in the national flag, making his final journey home not as the president he never became, but as something perhaps more remarkable: a leader whose influence transcended the very office he perpetually sought but never attained.

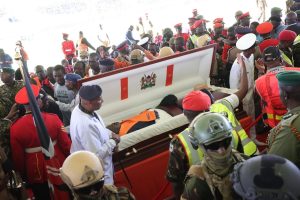

The Kenya Air Force jet hands over Raila Odinga’s body to Kenya Air Force chopper that will directly lift the body to Mamboleo Grounds in Kisumu.

The spectacle that unfolded across four days, from the moment news broke of Odinga’s death in India to his interment at Kang’o ka Jaramogi in Bondo, represented an unprecedented convergence of state power, cultural tradition, and popular emotion that Kenya had never witnessed for anyone outside the presidency.

That Raila Odinga received full military honours comparable only to those accorded former heads of state speaks to a profound shift in how the Kenyan state chooses to remember its most consequential figures, regardless of whether they ever occupied State House.

The honours bestowed upon Odinga were methodical in their symbolism.

His casket, borne by military pallbearers on a gun carriage through the streets of Nairobi, his body lying in state in Parliament, the military processions in three cities, and the gun salute at his burial site represented a checklist of ceremonial dignity that only four other Kenyans had received before him: presidents Jomo Kenyatta, Daniel arap Moi, and Mwai Kibaki, along with General Francis Ogolla, who died in office as Chief of Defence Forces.

Even Michael Kijana Wamalwa, who perished while serving as vice president in 2003, did not receive the full complement of these military honours.

The decision by President William Ruto to accord Odinga a state funeral marked a historic departure from Kenya’s traditional treatment of opposition figures.

For decades, the relationship between the state and its most vocal critics remained adversarial even in death. But Ruto’s gesture, political though it undoubtedly was, signalled something deeper about Kenya’s maturing democracy.

It acknowledged that Odinga’s contribution to the nation’s political evolution, his decades of struggle for constitutional reform, his role in the return of multiparty democracy, and his capacity to mobilise millions made him a statesman whose legacy belonged to all Kenyans, not merely to his Orange Democratic Movement party or to his Luo community.

The spontaneous outpouring of public grief disrupted even the most carefully laid government plans.

At Jomo Kenyatta International Stadium in Kisumu, what was intended as an orderly public viewing descended into controlled chaos as the 30,000-capacity facility overflowed with mourners, thousands more locked outside its gates.

Security planners had envisioned a stately procession from Kisumu to Bondo, but the sheer weight of humanity forced Interior Principal Secretary Raymond Omollo to abandon those plans and instead airlift the body by military helicopter.

The people, it seemed, would not be choreographed.

This popular defiance of official protocol had precedent in Kenyan history. When Jaramogi Oginga Odinga died in January 1994, tens of thousands followed his body from Kisumu to Bondo on foot, chanting freedom songs and waving palm branches in what became a spontaneous demonstration of love that no government decree could contain. But where Jaramogi’s funeral occurred during the tense early years of Kenya’s renewed multiparty democracy, when the state viewed the Odinga influence with suspicion and maintained oppressive security measures, his son’s sendoff unfolded in a vastly different political climate.

The government was not merely tolerating the mourning; it was orchestrating it.

Yet for all the state’s involvement, Raila’s funeral remained authentically rooted in Luo cultural traditions, creating a fascinating hybrid of military precision and ancestral ritual.

The performance of Tero Buru, the ceremonial driving away of death from the homestead, saw mourners break through security barriers at Odinga’s Opoda farm, dressed in traditional attire, armed with spears and shields, driving cattle and invoking ancestral spirits.

The Anglican Church, under Bishop David Kodia of Bondo Diocese, negotiated this cultural minefield with diplomatic skill, allowing traditions deemed not harmful while maintaining that the actual burial service would be a Christian affair.

The choice of burial site itself became a matter of cultural and familial negotiation that revealed the tensions inherent in honouring a man who straddled tradition and modernity.

Some elders argued that Odinga should rest at Opoda, the home he had established after leaving his father’s compound, following the Luo custom of goyo dala, where sons create their own homesteads. Others insisted he belonged beside Jaramogi at the family cemetery in Kang’o ka Jaramogi.

The latter view prevailed, and a mausoleum was constructed to house Raila alongside his father, physically reuniting in death two men who had shaped Kenya’s political consciousness across seven decades.

What distinguished Raila’s funeral most profoundly from any that preceded it was this unique combination of elements: the full machinery of state power deployed for an opposition leader, the integration of indigenous cultural practices into official ceremony, and the sheer scale of public participation that repeatedly overwhelmed security arrangements.

When mourners in Nairobi forced their way past barricades at Kasarani Stadium on Thursday, or when they stormed into the viewing at Jomo Kenyatta Stadium in Kisumu on Saturday, they were not merely grieving; they were asserting ownership over the narrative of Odinga’s life and death.

Mourners gather to receive the body of former Prime Minister Raila Odinga at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport on October 16, 2025. Photo credit: PCS

This was, as one headline captured it, the people’s funeral.

The symbolism extended beyond ceremony into political reconciliation. Just as Jaramogi had reconciled with President Daniel arap Moi before his death in 1994, so too had Raila reached an accommodation with President Ruto in the final year of his life.

But where Jaramogi’s rapprochement with Moi was viewed with suspicion by younger opposition leaders who saw it as betrayal, Raila’s working relationship with Ruto appeared to have Bishop Kodia’s blessing.

The cleric urged mourners to respect decisions Odinga had made before death, including his cooperation with the government, suggesting that even in his final political pivot, Raila retained the trust of his supporters.

The funeral also marked a generational shift in how Kenyans mourn their leaders. Mzee Onyango Radiel, who served as Jaramogi’s aide and witnessed both father and son’s funerals, observed that where people gathered for Jaramogi out of traditional loyalty, they came for Raila out of something resembling spiritual connection.

Raila, he suggested, had inspired faith in democracy the way prophets inspire faith in divinity.

This transformation from ethnic champion to national icon, from regional kingpin to statesman, was perhaps Odinga’s greatest achievement, one that only became fully visible in the breadth of mourning that accompanied his passing.

The contrast with Jaramogi’s funeral illuminated how far Kenya had travelled in 31 years. When the elder Odinga died, the state maintained nervous distance, wary of the opposition’s capacity for mobilisation.

At Jaramogi’s first anniversary in 1995, that wariness proved justified when police clashed with mourners in violence that left the event blood-stained and saw even visiting Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo later arrested and charged with treason upon his return home for allegedly plotting with Kenya’s opposition. No such tensions marred Raila’s sendoff.

The teargas incident at Kasarani that so distressed Oburu Oginga, who pleaded that his brother not be subjected to the chemical irritant in death as he had been countless times in life, was an aberration rather than the norm.

The media coverage itself represented a departure from tradition. Where Jaramogi’s death struck suddenly with no advance warning, Raila’s passing in a hospital in India allowed for preparation, for the mobilisation of resources, and for the kind of saturation coverage that social media enables.

The hashtags, the live streams, the minute-by-minute updates transformed a funeral into a national event experienced simultaneously by millions, collapsing the distance between Bondo and Nairobi, between Kenya and its diaspora.

The traditional mourning song “Jowi! Jowi!” became a viral phenomenon, its haunting refrain carrying across digital networks and physical spaces alike.

In the final analysis, what made Raila Odinga’s funeral the first of its kind in Kenyan history was not any single element but rather the unprecedented combination of factors that converged in those October days.

It was the first time the full apparatus of state honour was extended to someone who never held executive office.

It was the first time military tradition, Christian ceremony, and indigenous cultural practices were so deliberately and publicly interwoven.

It was the first time a funeral became both a state occasion and a popular uprising, where official protocol repeatedly gave way to the will of mourners who refused to be contained.

Most significantly, it represented the first time Kenya buried a leader whose legitimacy derived not from state power but from moral authority, not from electoral victory but from decades of struggle, not from the office he held but from the millions who believed in the vision he represented.

As dusk settled over the twin tombs at Kang’o ka Jaramogi, father and son reunited beneath marble and earth, it became clear that Kenya had found a new way to honour its heroes.

The presidency, that office Raila Odinga pursued through five elections and never attained, suddenly seemed less important than the question President Ruto posed during the memorial service: “Who will cry when you die?”

For Raila Amolo Odinga, the answer thundered across four days and three cities, delivered by a nation that wept.

A mourner overwhelmed by grief at Mamboleo grounds where thousands da turned up for the public viewing of Raila’s body in Kisumu.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoRussian Man’s Secret Sex Recordings Ignite Fury as Questions Mount Over Consent and Easy Pick-Ups in Nairobi

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoMulti-Million Dollar Fraud: Three Kenyans Face US Extradition in Massive Cybercrime Conspiracy

-

Economy1 week ago

Economy1 week agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Africa1 week ago

Africa1 week agoFBI Investigates Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s Husband’s Sh3.8 Billion Businesses in Kenya, Somalia and Dubai

-

Grapevine3 days ago

Grapevine3 days agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoSifuna, Babu Owino Are Uhuru’s Project, Orengo Is Opportunist, Inconsequential in Kenyan Politics, Miguna Says