Africa

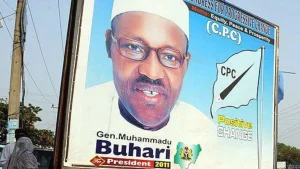

Former Nigerian Leader Muhammadu Buhari Dies Aged 82

The former president, who served as Nigeria’s leader in two different eras, died peacefully surrounded by close family.

Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari, who has died age 82 in a London clinic, was a former military ruler and self-styled converted democrat who returned to power through elections but struggled to convince Nigerians he could deliver on the change he promised.

Never a natural politician, he was seen as aloof and austere. But he retained a reputation for personal honesty – a rare feat for a politician in Nigeria.

After three failed attempts, Buhari achieved a historic victory in 2015, becoming the country’s first opposition candidate to defeat an incumbent. In 2019, he was re-elected for another four-year term.

Buhari had always been popular among the poor of the north (known as the “talakawa” in the Hausa language) but for the 2015 campaign, he had the advantage of a united opposition grouping behind him.

Many of those who supported him thought his military background and disciplinarian credentials were what the country needed to get to grips with the Islamist insurgency in the north. Buhari also promised to tackle corruption and nepotism in government, and create employment opportunities for young Nigerians.

But his time in office coincided with a slump in global oil prices and the country’s worst economic crisis in decades.

His administration also came under fire for its handling of insecurity. While campaigning he had promised to defeat the Islamist militant group Boko Haram. But the group remains a threat and one of its factions is now affiliated to the so-called Islamic State group.

There was also an upsurge in deadly clashes between farmers and ethnic Fulani herders in central Nigeria. Mr Buhari, a Fulani, was accused of not being tough enough on the herders or doing enough to stop the crisis.

The activities of so-called bandits in the north-western part of the country saw the abduction of hundreds of secondary school students.

Under his watch armed forces were accused of human rights abuses – like opening fire on anti-police brutality protesters at the Lekki tollgate in Lagos in October 2020.

Muhammadu Buhari was born in December 1942 in Daura in Katsina state in the far north of Nigeria, near the border with Niger. At the time, Nigeria was controlled by the British and it would be another 18 years before the country gained independence.

Buhari’s father, who died when he was four, was Fulani, while his mother, who brought him up, was Kanuri. In a 2012 interview, Buhari spoke of being his father’s 23rd child and his mother’s 13th. He said his only recollection of his father was of the two of them and one of his half-brothers being thrown from the back of a horse.

The young Buhari attended primary school in Daura and then boarding school in the city of Katsina. After leaving school, he was admitted to the Nigerian Military Training College, joining the Nigerian army shortly after independence.

Buhari undertook officer training in the UK from 1962-1963 and then began his steady climb up the ranks.

In later years, Buhari attributed his disciplinarian bent to spending his formative years at boarding school, where corporal punishment was the norm, and in the military. He was “lucky” to have experienced such tough environments, which taught him to work hard, he said.

In 1966, there was a military coup and then counter-coup in Nigeria – a time of upheaval for army officers but Buhari always maintained he was too junior to have played any significant role.

Less than 10 years later, under a military government, Buhari had risen to become military governor of the north-east, an area then comprising six states.

After less than a year, Buhari, now in his mid-30s, was promoted again, becoming federal commissioner for petroleum and natural resources (in effect oil minister) in 1976 under Olusegun Obasanjo in his first spell as Nigerian head of state.

Indiscipline and corruption

By 1978, Buhari, then a colonel, had returned to being a military commander. His tough stance in 1983 – when some Nigerian islands were annexed in Lake Chad by Chadian soldiers – is still remembered in the north-east, after he blockaded the area and drove off the invaders.

The end of 1983 saw another coup, against elected President Shehu Shagari, and Buhari, now a major-general, became the country’s military ruler. By his own account, he was not one of the plotters but was installed (and subsequently discarded) by those who held the real power and needed a figurehead.

Other accounts suggest he played a more active role in removing Shagari than he was willing to admit.

Buhari ruled for 20 months, a period remembered for a campaign against indiscipline and corruption, as well as for human rights abuses.

About 500 politicians, officials and businessmen were jailed as part of a campaign against waste and corruption.

Some saw this as the heavy-handed repression of military rule. Others remember it as a praiseworthy attempt to fight the endemic corruption that was holding back Nigeria’s development.

Buhari retained a rare reputation for honesty among Nigeria’s politicians, both military and civilian, largely because of this campaign.

As part of his “war against indiscipline”, he ordered Nigerians to form neat queues at bus stops, under the sharp eyes of whip-wielding soldiers. Civil servants who were late for work were publicly humiliated by being forced to do frog jumps.

Some of his measures might have been seen as merely eccentric. But others were genuinely repressive, such as a decree to restrict press freedom, under which journalists were jailed.

Buhari’s government also locked up Nigeria’s greatest musical hero, Fela Kuti – a thorn in the side of successive leaders – on trumped-up charges relating to currency exports.

Buhari’s attempts to re-balance the public finances by curbing imports led to many job losses and the closure of businesses.

As part of anti-corruption measures, he also ordered that the currency be replaced – the colour of the naira notes was changed – forcing all holders of old notes to exchange them at banks within a limited period.

Prices rose while living standards fell, and in August 1985 Buhari was ousted and imprisoned for 40 months. Army chief Gen Ibrahim Babangida took over.

Historic election victory

After his release and, he said, having seen the consequences of the break-up of the Soviet Union, Buhari decided to enter party politics, now convinced of the virtues of multiparty democracy and free and fair elections.

Despite this, Buhari always defended the 1983 coup, saying in 2005: “The military came in when it was absolutely necessary and the elected people had failed the country.”

He also rejected accusations that his measures against journalists and others had gone too far, insisting that he had been merely applying the laws that others had been breaking.

He was elected president in 2015, becoming the first opposition candidate to defeat an incumbent since the return of multiparty democracy in 1999.

As president, Buhari made a virtue of his “incorruptibility”, declaring his relatively modest wealth and saying he had “spurned several past opportunities” to enrich himself.

He was plain spoken by nature, which sometimes played well for him in the media and sometimes badly.

Although few doubted his personal commitment to fighting corruption and there were several notable scalps, some questioned whether the structures enabling mismanagement had really been reformed.

And attempts to improve youth employment prospects were, at best, a work in progress.

On the day Buhari left office, some Nigerians were asked in a video that was widely shared on social media, what they would remember most about his time in office, and all respondents said the same thing: ‘Bag of rice’.

The reason was simple – rice is the staple food in the country.

A standard 50kg (110lb) bag of rice, which could help feed a household of between eight and 10 for about a month, cost just 7,500 naira ($5; £3) under President Goodluck Jonathan, who was defeated by Buhari in 2015, but went up to 60,000 naira a few years afterwards.

This led to hunger in many parts of the country.

The huge surge in the price of rice was because, in an echo of his earlier policy as a military ruler, Buhari banned the importation of rice to encourage more Nigerian farmers to grow the crop.

However, local producers were unable to meet the high demand and many of his supporters lost their faith in him.

Ismail Danyaro, a resident of the northern city of Kano, said he had backed Buhari since he first contested the presidency in 2003.

“I used to buy a 50kg bag of rice under Goodluck [Jonathan] but when Buhari came, I found it difficult to buy even a 25kg bag of rice because it became so expensive,” he told the BBC.

At one point, even Buhari’s wife threatened not to support his re-election bid.

‘Baba go slow’

Nigerians love nicknames and some of the country’s leaders’ nicknames have stuck even long after they left office.

For example, former military leader Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida is still called “Maradona” for what people perceived as his tactical dribbles on issues and situations.

For Buhari, it was “Baba [Father] go slow” after it took him six months to name his first cabinet on assuming office in 2015.

Responding to his nickname years later, Buhari said it wasn’t his fault that it took so long to get anything done.

“Yes, we are slow because the system is slow. It’s not Baba that is slow but it is the system so I am going by this system and I hope we will make it,” he said in 2018.

Nigerian politics in 2022-2023 remains one of the most interesting in the country’s democratic history.

In the minds of many, it was the first time that a sitting president wasn’t really bothered about who his successor was going to be.

Openly, Buhari declared he would support whoever won his party’s (All Progressives Congress) nomination but insiders say behind the scenes he was ambivalent.

Buhari’s body language emboldened all five candidates seeking the APC’s endorsement and their supporters all went around saying they had his backing.

At one point it felt as if Buhari opposed the candidacy of his eventual successor, Bola Tinubu.

What followed was the declaration of the “naira swap policy” which the Buhari administration announced would, among other things, limit the influence of money in the 2023 elections.

Many Nigerians believed that the policy was targeted at preventing Tinubu from becoming president even though he had been chosen as the APC candidate.

The policy involved the confiscation of trillions of old naira notes and their replacement with new notes for the highest denominations.

However, there were not enough new notes, leading to shortages and suffering by millions, particularly the less well-off, who rely on cash for their daily transactions.

The policy was only suspended after a Supreme Court ruling, just days before the election.

Tinubu won narrowly, with 37% of votes cast, as the opposition was divided.

Any assessment of Buhari’s presidency must take account his declining health, which caused him to take significant absences from work, especially during his first term.

The former military ruler may have reinvented himself as a democrat but there was no such commitment to transparency concerning his own health, with Nigerians left uninformed about the fitness of their head of state for office.

Muhammadu Buhari married twice, first to Safinatu Yusuf from 1971-1988, and then in 1989 to Aisha Halilu, who survives him. He had 10 children.

(BBC)

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Grapevine2 weeks ago

Grapevine2 weeks agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Development3 days ago

Development3 days agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Close Ruto Allies Make Billions From Affordable Housing Deals

-

Entertainment2 weeks ago

Entertainment2 weeks agoKRA Comes for Kenyan Prince After He Casually Counted Millions on Camera

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoI Personally Paid For Your Ticket To Visit Raila in India, Oketch Salah Silences Ruth Odinga After Claiming She Barely Knew Him

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoAmerican Investor Claims He Was Scammed Sh225 Million in 88 Nairobi Real Estate Deal