Africa

EXCLUSIVE: The Billion Dollar Oil Heist – How Shadow Networks Are Bleeding South Sudan Dry

The predation operates on two levels simultaneously. On the surface, Euroamerica and Cathay simply capture cargoes through political connections and sell them at manipulated prices that shortchange the South Sudanese state.

A Kenya Insights Investigation

South Sudan’s oil wealth is vanishing into a labyrinth of shell companies, corrupt intermediaries and recycled traders with histories of bribery and fraud. At the center of this sophisticated looting operation stands an obscure Hong Kong firm that has suddenly seized control of the young nation’s economic lifeline while a British operator with a career built on embargo-busting orchestrates the largest systematic theft in the country’s history.

Documents and sources reviewed by Kenya Insights reveal that Cathay Petroleum, a company that spent fifteen years in relative obscurity, now commands the lion’s share of South Sudanese crude exports through an alliance with Euroamerica Energy, a clandestine operation run by Idris Taha, a Northern Sudanese businessman who has made a career operating in the world’s most corrupt oil markets.

Together with dismissed Vice President Benjamin Bol Mel and a network of facilitators including Dutch national Cornelis Nicolaas Abraham Loos, they have constructed what investigators describe as an integrated predatory ecosystem that siphons hundreds of millions of dollars from one of Africa’s poorest nations.

The scale of the operation is staggering. Euroamerica Energy currently controls more than eighty percent of crude cargoes exported from South Sudan in recent months, with two out of three shipments in November and three out of four in December flowing through channels that bypass every financial oversight mechanism in the country.

No prepayments reach the Ministry of Finance. No records land at the Central Bank. The opacity is so complete that it directly contributed to the recent arrest of the Central Bank Governor, sources familiar with the matter confirmed.

The architecture of this theft draws on a playbook perfected over decades in Libya, Yemen, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Cathay Petroleum was founded in March 2003 by a Chinese national operating between Hong Kong and Singapore with a specialty in crude oil trading from sanctioned or sensitive countries.

The company first appeared in the early 2010s as what industry insiders call a sleeve, a shell company used by Arcadia Petroleum, the now-defunct London trading house that operated extensively in South Sudan, Yemen and Nigeria.

Arcadia’s collapse in 2018 came amid allegations of massive internal fraud involving USD 349 million. Several former directors were accused of using shell companies, including Cathay Petroleum, to divert funds.

The case was ultimately dismissed due to lack of evidence but the traders at the heart of those schemes simply moved on.

Some joined Glencore, the Swiss commodities giant that later publicly admitted paying bribes in South Sudan and faced corruption charges in Cameroon and the DRC.

When Glencore exited South Sudan under the weight of scandal, those same traders migrated to Cathay Petroleum, bringing with them not just expertise but entire networks of fixers and intermediaries.

This is where Idris Taha enters the picture.

The Managing Director of Euroamerica Energy holds both British and German passports and has spent his career in what intelligence analysts describe as grey zones.

He began in Libya in the 1990s during the embargo years, working through the oil for medicine programme that was systematically corrupted by parallel networks.

After the fall of Gaddafi in 2011, Taha shifted to Iran, managing large contracts with the United Arab Emirates until those relationships collapsed amid accusations of deception.

Now persona non grata in the Emirates, he operates primarily between Turkey, where he partners with BGN, and the United Kingdom.

Taha’s resume reads like a catalogue of commodity trading scandals.

He previously represented Trafigura in South Sudan before that company fled the country following its own bribery scandal.

He then joined Litasco, the trading arm of Russian oil giant Lukoil, whose withdrawal from South Sudan left behind an unpaid debt of USD 90 million.

Through it all, Taha cultivated relationships with South Sudanese officials, particularly Benjamin Bol Mel, the former Vice President dismissed in mid-November, and General Manasa Machar, who oversees Security and Compliance at the Ministry of Petroleum.

The predation operates on two levels simultaneously. On the surface, Euroamerica and Cathay simply capture cargoes through political connections and sell them at manipulated prices that shortchange the South Sudanese state.

But the more insidious theft happens upstream through the cost oil mechanism, a system designed to allow oil companies to recoup exploration and production expenses before the government receives its share.

In theory, cost oil is a standard arrangement. In practice, it has become a vehicle for organized overbilling on a breathtaking scale.

Oil service companies linked to Bol Mel, Loos and Taha charge up to three times standard prices for drilling and services, knowing the cost oil system will reimburse every inflated dollar before a single cent reaches public coffers.

A well that should cost USD 20 million is billed at USD 100 million and the state absorbs the entire loss. There is no ceiling on these costs and no meaningful verification.

The system structurally incentivizes theft.

Cornelis Loos has been in South Sudan for over seven years serving as a close associate of Bol Mel and a key collaborator with General Manasa Machar.

He manages money laundering operations through Dubai and has handled UAE real estate assets on behalf of the former Vice President.

Sources describe him as a central facilitator of opaque financial flows, the man who makes the mechanics of corruption work smoothly across jurisdictions and banking systems.

The family nature of the network adds another layer of opacity.

Because Idris Taha faces travel restrictions in certain jurisdictions, his son Mahmoud Taha conducts meetings on his father’s behalf, regularly interfacing with Benjamin Bol Mel and other South Sudanese officials.

The arrangement allows the elder Taha to remain in the shadows while his son serves as the public face of Euroamerica’s operations.

What makes this network particularly dangerous is its institutional depth.

This is not a simple case of officials taking bribes.

It is a complete capture of the country’s primary revenue stream by a syndicate with decades of experience evading sanctions, manipulating markets and exploiting weak governance.

The traders at Cathay Petroleum learned their craft at Arcadia and Glencore, companies that pioneered aggressive trading in frontier markets.

Idris Taha built his career navigating embargoes in Libya and Iran.

Loos provides the financial infrastructure to move money across borders without detection. Bol Mel and Manasa Machar provide political protection and access.

The system works because everyone profits except the South Sudanese people. Cathay gets cargoes at favorable terms.

Euroamerica controls allocation and captures the margin between real costs and inflated bills. Service companies charge triple rates.

Officials receive payments through offshore structures.

The money flows through Dubai, Turkey, the UK and various shell companies while South Sudan’s treasury remains empty and its people endure poverty despite sitting atop significant oil reserves.

The recent surge in volumes allocated to Cathay Petroleum represents the final phase of network consolidation.

After years of building relationships and positioning assets, the syndicate now controls the majority of the country’s crude exports through structures designed for maximum opacity.

There are no prepayments that would create a paper trail.

No audits that might reveal the true scale of overbilling.

No meaningful oversight from financial institutions that have either been captured or deliberately bypassed.

International investigators familiar with commodity trading patterns say the red flags are impossible to ignore.

The sudden dominance of a previously minor player. The historical continuity with networks known for sanctions evasion.

The synergy between trading companies, service providers, intermediaries and political figures.

The complete absence of financial transparency.

The inflation of costs to levels that defy economic logic.

The routing of funds through jurisdictions known for lax enforcement of money laundering controls.

South Sudan has been bled by conflict, mismanagement and corruption since independence but this represents something more systematic and more sophisticated than the typical looting that afflicts resource-rich African nations.

This is infrastructure-level theft, the capture of an entire export system by a transnational network with the expertise to keep it running indefinitely.

The traders involved have operated successfully in Libya under Gaddafi, in Yemen during civil war, in Sudan under sanctions and in multiple jurisdictions where Glencore faced prosecution.

They know how to structure deals that resist investigation.

They know which officials to cultivate and how to compensate them discreetly.

They know which banks and jurisdictions will look the other way.

For South Sudan, the implications are catastrophic. Oil revenues that should fund basic services, infrastructure and development instead disappear into offshore accounts.

The cost oil mechanism that should help develop petroleum resources has become a vehicle for systematic overbilling that ensures the state never sees meaningful returns.

The Ministry of Finance and Central Bank have been effectively cut out of the export process, unable to track revenues or verify that the country receives fair value for its resources.

The dismissal of Benjamin Bol Mel in mid-November suggests that some elements within the South Sudanese government recognize the severity of the crisis but removing one official does little to dismantle a network this entrenched.

Idris Taha continues to operate freely from his bases in Turkey and the UK. Cathay Petroleum continues to lift cargoes.

Loos remains in the country facilitating financial flows.

General Manasa Machar retains his position overseeing security and compliance at the Ministry of Petroleum, a role that provides crucial protection for the entire operation.

The international community has largely failed to act despite clear evidence of massive corruption in South Sudan’s oil sector.

Glencore faced consequences for its admitted bribery but the traders who implemented those schemes simply moved to new employers and continued the same practices.

Arcadia collapsed under fraud allegations but the networks it built remain intact, now operating through Cathay Petroleum.

Trafigura and Litasco withdrew from South Sudan but Idris Taha, who worked for both companies, simply shifted to his own vehicle and expanded his control.

What the Cathay Petroleum and Euroamerica Energy network represents is the evolution of resource theft into a professional discipline practiced by specialists who move seamlessly between companies, countries and commodities.

They bring with them not just personal contacts but entire methodologies for circumventing oversight, manipulating pricing and extracting wealth from weak states.

They understand that in places like South Sudan, the combination of poor governance, conflict and international inattention creates opportunities for theft on a scale that would be impossible in more developed markets.

The hundreds of millions of dollars that have already been diverted represent only the beginning.

With more than eighty percent of current crude exports under their control and no meaningful oversight from financial authorities, the network is positioned to extract wealth from South Sudan for years to come.

Every inflated service contract, every underpriced cargo sale, every payment routed through Dubai or offshore structures represents money that will never reach hospitals, schools or infrastructure.

The human cost of this corruption is measured in development that never happens, in services that are never provided, in a generation of South Sudanese who will grow up in poverty while their country’s wealth flows to Hong Kong, London, Dubai and Ankara.

Kenya Insights attempted to reach Cathay Petroleum, Euroamerica Energy, Idris Taha and Cornelis Loos for comment.

None responded to requests.

The South Sudanese Ministry of Petroleum declined to comment on specific companies or individuals but said in a statement that it is committed to transparency in the oil sector and is working with international partners to strengthen oversight.

That statement rings hollow given that the ministry’s own Security and Compliance chief, General Manasa Machar, is identified by multiple sources as a key collaborator in the network.

The story of Cathay Petroleum and Euroamerica Energy is ultimately a story about impunity.

It demonstrates that for those with the right expertise and connections, stealing from the world’s poorest countries carries minimal risk and generates enormous rewards.

The traders involved have spent decades perfecting their craft in sanctioned and conflict-affected markets.

They know that even when caught, as Glencore was, the consequences are manageable.

Fines are paid from corporate accounts.

A few executives might face charges. But the networks survive, the traders move on and the theft continues under new corporate names.

South Sudan cannot afford this.

Already one of the world’s youngest and poorest nations, it needs every dollar of oil revenue to build the basic infrastructure of statehood.

Instead, those dollars are disappearing into a sophisticated theft machine operated by some of the world’s most experienced commodity traders in partnership with corrupt officials.

Until international law enforcement and financial regulators treat this systematic looting with the seriousness it deserves, the bleeding will continue and South Sudan’s oil wealth will remain a curse rather than a blessing for its people.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTHE FIRM IN THE DOCK: How Kaplan and Stratton Became the Most Scrutinised Law Firm in Kenya

-

Economy2 weeks ago

Economy2 weeks agoIran Demands Arrest, Prosecution Of Kenya’s Cup of Joe Director Director Over Sh2.6 Billion Tea Fraud

-

Grapevine1 week ago

Grapevine1 week agoA UN Director Based in Nairobi Was Deep in an Intimate Friendship With Epstein — He Even Sent Her a Sex Toy

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoA Farm in Kenya’s Rift Valley Ignites a National Reckoning With Israeli Investment

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoKPC IPO Set To Flop Ahead Of Deadline, Here’s The Experts’ Take

-

Politics2 weeks ago

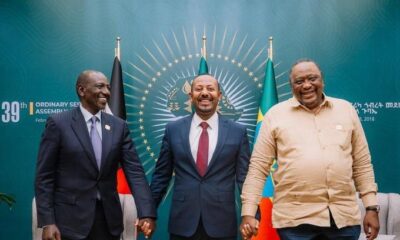

Politics2 weeks agoPresident Ruto and Uhuru Reportedly Gets In A Heated Argument In A Closed-Door Meeting With Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow Mexico Drug Lord’s Girlfriend Gave Him Away

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSafaricom Faces Avalanche of Lawsuits Over Data Privacy as Acquitted Student Demands Sh200mn Compensation in 48 Hours