Investigations

A Leaked File Reveals How Uber broke laws, duped police and secretly lobbied governments across the World during its aggressive global expansion.

The unprecedented leak to the Guardian of more than 124,000 documents – known as the Uber files – lays bare the ethically questionable practices that fuelled the company’s transformation into one of Silicon Valley’s most famous exports.

The leak spans a five-year period when Uber was run by its co-founder Travis Kalanick, who tried to force the cab-hailing service into cities around the world, even if that meant breaching laws and taxi regulations.

During the fierce global backlash, the data shows how Uber tried to shore up support by discreetly courting prime ministers, presidents, billionaires, oligarchs and media barons.

Leaked messages suggest Uber executives were at the same time under no illusions about the company’s law-breaking, with one executive joking they had become “pirates” and another conceding: “We’re just fucking illegal.”

The cache of files, which span 2013 to 2017, includes more than 83,000 emails, iMessages and WhatsApp messages, including often frank and unvarnished communications between Kalanick and his top team of executives.

In one exchange, Kalanick dismissed concerns from other executives that sending Uber drivers to a protest in Franceput them at risk of violence from angry opponents in the taxi industry. “I think it’s worth it,” he shot back. “Violence guarantee[s] success.”

In a statement, Kalanick’s spokesperson said he “never suggested that Uber should take advantage of violence at the expense of driver safety” and any suggestion he was involved in such activity would be completely false.

The leak also contains texts between Kalanick and Emmanuel Macron, who secretly helped the company in France when he was economy minister, allowing Uber frequent and direct access to him and his staff.

Macron, the French president, appears to have gone to extraordinary lengths to help Uber, even telling the company he had brokered a secret “deal” with its opponents in the French cabinet.

Privately, Uber executives expressed barely disguised disdain for other elected officials who were who were less receptive to the company’s business model.

After the German chancellor, Olaf Scholz, who was mayor of Hamburg at the time, pushed back against Uber lobbyists and insisted on paying drivers a minimum wage, an executive told colleagues he was “a real comedian”.

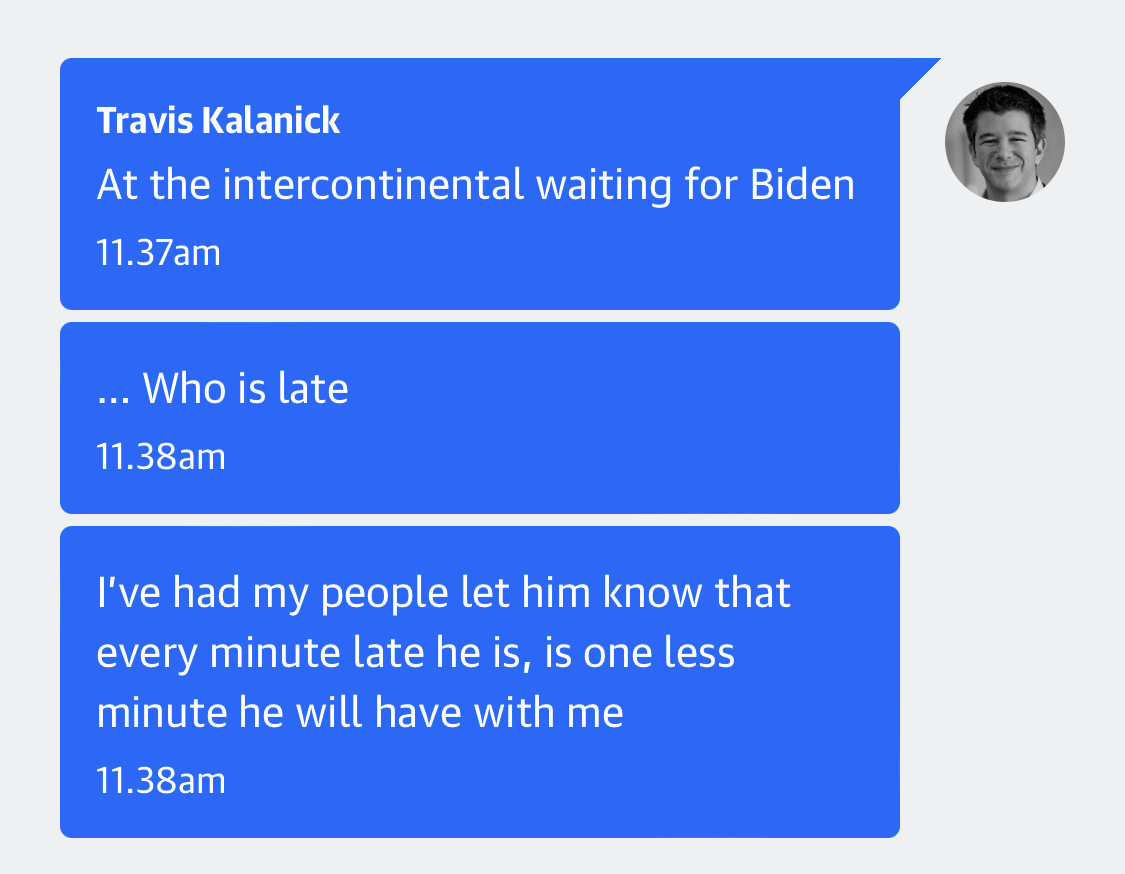

When the then US vice-president, Joe Biden, a supporter of Uber at the time, was late to a meeting with the company at the World Economic Forum at Davos, Kalanick texted a colleague: “I’ve had my people let him know that every minute late he is, is one less minute he will have with me.”

After meeting Kalanick, Biden appears to have amended his prepared speech at Davos to refer to a CEO whose company would give millions of workers “freedom to work as many hours as they wish, manage their own lives as they wish”.

The Guardian led a global investigation into the leaked Uber files, sharing the data with media organisations around the world via the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). More than 180 journalists at 40 media outlets including Kenya insights, Le Monde, Washington Post and the BBC will in the coming days publish a series of investigative reports about the tech giant.

In a statement responding to the leak, Uber admitted to “mistakes and missteps”, but said it had been transformed since 2017 under the leadership of its current chief executive, Dara Khosrowshahi.

“We have not and will not make excuses for past behaviour that is clearly not in line with our present values,” it said. “Instead, we ask the public to judge us by what we’ve done over the last five years and what we will do in the years to come.”

Kalanick’s spokesperson said Uber’s expansion initiatives were “led by over a hundred leaders in dozens of countries around the world and at all times under the direct oversight and with the full approval of Uber’s robust legal, policy and compliance groups”.

‘Embrace the chaos’

The leaked documents pull back the curtains on the methods Uber used to lay the foundations for its empire. One of the world’s largest work platforms, Uber is now a $43bn (£36bn) company, making approximately 19m journeys a day.

The files cover Uber’s operations across 40 countries during a period in which the company became a global behemoth, bulldozing its cab-hailing service into many of the cities in which it still operates today.

From Moscow to Johannesburg, bankrolled with unprecedented venture capital funding, Uber heavily subsidised journeys, seducing drivers and passengers on to the app with incentives and pricing models that would not be sustainable.

Uber undercut established taxi and cab markets and put pressure on governments to rewrite laws to help pave the way for an app-based, gig-economy model of work that has since proliferated across the world.

In a bid to quell the fierce backlash against the company and win changes to taxi and labour laws, Uber planned to spend an extraordinary $90m in 2016 on lobbying and public relations, one document suggests.

Its strategy often involved going over the heads of city mayors and transport authorities and straight to the seat of power.

In addition to meeting Biden at Davos, Uber executives met face-to-face with Macron, the Irish prime minister, Enda Kenny, the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and George Osborne, the UK’s chancellor at the time. A note from the meeting portrayed Osborne as a “strong advocate”.

In a statement, Osborne said it was the explicit policy of the government at the time to meet with global tech firms and “persuade them to invest in Britain, and create jobs here”.

While the Davos sitdown with Osborne was declared, the data reveals that six UK Tory cabinet ministers had meetings with Uber that were not disclosed. It is unclear if the meetings should have been declared, exposing confusion around how UK lobbying rules are applied.

The documents indicate Uber was adept at finding unofficial routes to power, applying influence through friends or intermediaries, or seeking out encounters with politicians at which aides and officials were not present.

It enlisted the backing of powerful figures in places such as Russia, Italy and Germany by offering them prized financial stakes in the startup and turning them into “strategic investors”.

And in a bid to shape policy debates, it paid prominent academics hundreds of thousands of dollars to produce research that supported the company’s claims about the benefits of its economic model.

Despite a well-financed and dogged lobbying operation, Uber’s efforts had mixed results. In some places Uber succeeded in persuading governments to rewrite laws, with lasting effects. But elsewhere, the company found itself blocked by entrenched taxi industries, outgunned by local cab-hailing rivals or opposed by leftwing politicians who simply refused to budge.

When faced with opposition, Uber sought to turn it to its advantage, seizing upon it to fuel the narrative its technology was disrupting antiquated transport systems, and urging governments to reform their laws.

As Uber launched across India, Kalanick’s top executive in Asia urged managers to focus on driving growth, even when “fires start to burn”. “Know this is a normal part of Uber’s business,” he said. “Embrace the chaos. It means you’re doing something meaningful.”

Kalanick appeared to put that ethos into practice in January 2016, when Uber’s attempts to upend markets in Europe led to angry protests in Belgium, Spain, Italy and France from taxi drivers who feared for their livelihoods.

Amid taxi strikes and riots in Paris, Kalanick ordered French executives to retaliate by encouraging Uber drivers to stage a counter-protest with mass civil disobedience.

Warned that doing so risked putting Uber drivers at risk of attacks from “extreme right thugs” who had infiltrated the taxi protests and were “spoiling for a fight”, Kalanick appeared to urge his team to press ahead regardless. “I think it’s worth it,” he said. “Violence guarantee[s] success. And these guys must be resisted, no? Agreed that right place and time must be thought out.”

The decision to send Uber drivers into potentially volatile protests, despite the risks, was consistent with what one senior former executive told the Guardian was a strategy of “weaponising” drivers, and exploiting violence against them to “keep the controversy burning”.

It was a playbook that, leaked emails suggest, was repeated in Italy, Belgium, Spain, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

When masked men, reported to be angry taxi drivers, turned on Uber drivers with knuckle-dusters and a hammer in Amsterdam in March 2015, Uber staffers sought to turn it to their advantage to win concessions from the Dutch government.

Driver victims were encouraged to file police reports, which were shared with De Telegraaf, the leading Dutch daily newspaper. They “will be published without our fingerprint on the front page tomorrow”, one manager wrote. “We keep the violence narrative going for a few days, before we offer the solution.”

Kalanick’s spokesperson questioned the authenticity of some documents. She said Kalanick “never suggested that Uber should take advantage of violence at the expense of driver safety” and any suggestion that he was involved in such activity would be “completely false”.

Uber’s spokesperson also acknowledged past mistakes in the company’s treatment of drivers but said no one, including Kalanick, wanted violence against Uber drivers. “There is much our former CEO said nearly a decade ago that we would certainly not condone today,” she said. “But one thing we do know and feel strongly about is that no one at Uber has ever been happy about violence against a driver.”

The ‘kill switch’

Uber drivers were undoubtedly the target of vicious assaults and sometimes murders by furious taxi drivers. And the cab-hailing app, in some countries, found itself battling entrenched and monopolised taxi fleets with cosy relationships with city authorities. Uber often characterised its opponents in the regulated taxi markets as operating a “cartel”.

However, privately, Uber executives and staffers appear to have been in little doubt about the often rogue nature of their own operation.

In internal emails, staff referred to Uber’s “other than legal status”, or other forms of active non-compliance with regulations, in countries including Turkey, South Africa, Spain, the Czech Republic, Sweden, France, Germany, and Russia.

One senior executive wrote in an email: “We are not legal in many countries, we should avoid making antagonistic statements.” Commenting on the tactics the company was prepared to deploy to “avoid enforcement”, another executive wrote: “We have officially become pirates.”

Nairi Hourdajian, Uber’s head of global communications, put it even more bluntly in a message to a colleague in 2014, amid efforts to shut the company down in Thailand and India: “Sometimes we have problems because, well, we’re just fucking illegal.” Contacted by the Guardian, Hourdajian declined to comment.

Kalanick’s spokesperson accused reporters of “pressing its false agenda” that he had “directed illegal or improper conduct”.

Uber’s spokesperson said that, when it started, “ridesharing regulations did not exist anywhere in the world” and transport laws were outdated for a smartphone era.

Across the world, police, transport officials and regulatory agencies sought to clamp down on Uber. In some cities, officials downloaded the app and hailed rides so they could crack down on unlicensed taxi journeys, fining Uber drivers and impounding their cars. Uber offices in dozens of countries were repeatedly raided by authorities.

Against this backdrop, Uber developed sophisticated methods to thwart law enforcement. One was known internally at Uber as a “kill switch”. When an Uber office was raided, executives at the company frantically sent out instructions to IT staff to cut off access to the company’s main data systems, preventing authorities from gathering evidence.

The leaked files suggest the technique, signed off by Uber’s lawyers, was deployed at least 12 times during raids in France, the Netherlands, Belgium, India, Hungary and Romania.

Kalanick’s spokesperson said such “kill switch” protocols were common business practice and not designed to obstruct justice. She said the protocols, which did not delete data, were vetted and approved by Uber’s legal department, and the former Uber CEO was never charged in relation to obstruction of justice or a related offence.

Uber’s spokesperson said its kill switch software “should never have been used to thwart legitimate regulatory action” and it had stopped using the system in 2017, when Khosrowshahi replaced Kalanick as CEO.

Another executive the leaked files suggest was involved in kill switch protocols was Pierre-Dimitri Gore-Coty, who ran Uber’s operations in western Europe. He now runs Uber Eats, and sits on the company’s 11-strong executive team.

Gore-Coty said in a statement he regretted “some of the tactics used to get regulatory reform for ridesharing in the early days”. Looking back, he said: “I was young and inexperienced and too often took direction from superiors with questionable ethics.”

Politicians now also face questions about whether they took direction from Uber executives.

When a French police official in 2015 appeared to ban one of Uber’s services in Marseille, Mark MacGann, Uber’s chief lobbyist in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, turned to Uber’s ally in the French cabinet.

“I will look at this personally,” Macron texted back. “At this point, let’s stay calm.”

By:The Guardian

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoEx-Inchcape Kenya CEO Sanjiv Shah Charged With Bank Fraud

-

Development1 week ago

Development1 week agoKenya Strips Dutch Climate Body of Diplomatic Immunity Amid Donor Fraud Scandal and Allegations of Executive Capture

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNIS Kismu Hotel Secret Tape That Sealed Gachagua’s Fate and MP Ng’eno Death in A Chopper Crash

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoInvestor Sued Over Sh30,000 Fee to Access Runda Road

-

Investigations1 day ago

Investigations1 day agoSOLD TO THE BULLET: How the Bodyguard Handed MP Ong’ondo Were to His Killers

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoDid Festus Omwamba Take the Fall? The Puzzle of a Senator’s Ouster and a Call to the CS

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoI Swore Never To Hire The Chopper Again, Author Recalls Harrowing Experience in Helicopter That Killed MP Ng’eno Alleges Poor Maintenance By Owners

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

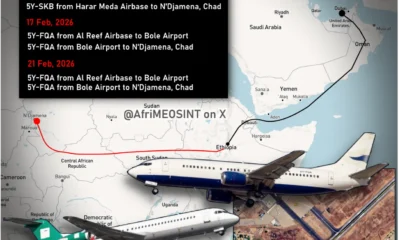

Investigations2 weeks agoTracker Identifies Kenyan-Registered Flights Allegedly Running Errands for RSF