Business

Lea Maize Flour Producer Admits to Adding Chemicals to Make Ugali ‘Balloon’ as Experts Issue Warnings

Calls are mounting for mandatory disclosure of all chemical additives on product labels, not buried in fine print but prominently displayed so consumers can make informed choices.

Nairobi, Kenya – October 3, 2025 – A shocking admission by New Paleah Millers, the company behind Lea Premium Maize Flour, has ignited a firestorm of controversy after a senior representative openly revealed on national television that the firm adds multiple chemical improvers to their product to make ugali appear bigger, whiter, and sweeter.

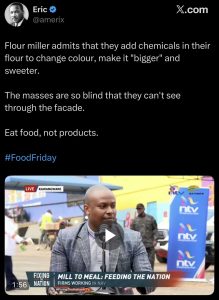

The revelation, captured during an NTV broadcast and subsequently amplified by renowned Kenyan nutritionist Amerix on social media, has sent shockwaves through households across the country, where maize flour remains the cornerstone of daily sustenance for millions of families.

In the damning interview aired on NTV’s “Fixing the Nation” segment, Douglas Kuria, New Paleah Millers CEO casually disclosed that the company incorporates “over five improvers” into Lea Premium Maize Flour, including various fortificants and chemical agents designed to alter the flour’s physical properties and extend its shelf life to four months.

“We add improvers to make the flour perform better, to make it balloon when cooking, and to give it a longer shelf life,” the representative stated matter-of-factly, seemingly oblivious to the alarm such an admission would trigger among health-conscious consumers.

The disclosure has been met with fury on social media, with Amerix, a prominent voice in Kenya’s nutrition and wellness community, leading the charge.

In a series of scathing posts tagged #FoodFriday, Amerix warned Kenyans to “avoid eating processed maize flour,” claiming the products are manufactured from imported cornstarch and bleached with chlorine dioxide and benzoyl peroxide to achieve their characteristic white appearance.

“They bleach with chlorine dioxide and benzoyl peroxide that is why it is white,” Amerix wrote, accompanying his posts with images of supermarket shelves stocked with multiple brands of processed maize flour. “Ever ask yourself why there are over 40 brands yet maize farmers are lamenting? Unlearn!”

His message concluded with a stark warning: “Eat food, not products.”

The timing of this revelation could not be worse for Kenya’s maize flour industry, which has been plagued by recurring safety scandals and mounting consumer distrust.

While government-mandated fortification programs, enacted under the Food, Drugs and Chemical Substances Act of 2012, require the addition of vitamins and minerals to combat widespread micronutrient deficiencies, critics argue that these regulations have opened the floodgates for excessive chemical manipulation of basic foodstuffs.

New Paleah Millers maintains that their chemical improvers are sourced with guidance from food scientists at Beckels and the Bula Group, companies that specialize in providing additives to ensure compatibility with maize varieties from different Kenyan regions.

However, the company has conspicuously declined to provide a comprehensive list of exactly which chemicals are being added to their flour or in what quantities.

This opacity has fueled suspicions among food safety advocates who point to the disturbing trend of millers prioritizing appearance and profitability over genuine nutritional value and consumer safety.

Dr. Catherine Wanjiru, a food safety specialist at the Kenya Nutritionists and Dieticians Institute, expressed grave concern about the practice.

“When companies start adding chemicals primarily to make food ‘look better’ rather than to improve its nutritional profile, we must ask: at what cost to public health? The chemicals used for bleaching and ‘improving’ texture are not nutrients. They’re processing agents, and some carry potential health risks with long-term exposure.”

The controversy surrounding processed maize flour extends far beyond cosmetic additives. Kenya’s maize supply chain has been haunted by the specter of aflatoxin contamination for decades, with devastating consequences that have claimed lives and damaged the health of countless Kenyans.

Aflatoxins, deadly carcinogenic compounds produced by Aspergillus fungi, thrive in improperly stored maize, particularly in humid conditions. The toxins are invisible, tasteless, and odorless, making them impossible for consumers to detect without laboratory testing.

The deadliest aflatoxin outbreak in Kenya’s history occurred in 2004, when contaminated homegrown maize stored under damp conditions killed over 125 people and sickened 317 others in eastern Kenya.

The tragedy exposed catastrophic failures in Kenya’s food safety systems and storage practices that persist to this day.

More recent incidents confirm the ongoing nature of this threat.

In 2019, the Kenya Bureau of Standards suspended production of Dola and Kifaru maize flour brands after tests revealed aflatoxin levels exceeding the legal limit of 10 parts per billion. The contaminated products had already reached supermarket shelves before being recalled.

Just last year, in 2024, the Ministry of Health ordered immediate seizures of Sherehe GSM maize flour following detection of dangerously high aflatoxin content. Inspectors raided mills and destroyed contaminated batches, but questions remained about how many consumers had already been exposed.

What makes the current revelation about chemical additives particularly insidious is that fortification and “improvement” processes may actually mask the presence of aflatoxins and other contaminants in processed flour. By altering the color, texture, and appearance of maize flour through chemical treatment, millers could be concealing inferior or contaminated raw materials beneath a veneer of artificial enhancement.

“When you bleach flour to make it artificially white, you’re potentially hiding discoloration that might signal fungal contamination or poor quality maize,” explained Dr. James Kimani, a toxicologist at Kenyatta University. “The improvers that make ugali ‘balloon’ could be compensating for nutritionally inferior or damaged grain. Consumers deserve to know what they’re really eating.”

The practice of importing cornstarch for maize flour production, as alleged by Amerix, raises additional concerns about traceability and quality control. While some manufacturers blend imported cornstarch with local maize to extend supplies or reduce costs, this practice remains poorly regulated and rarely disclosed to consumers.

The proliferation of maize flour brands in Kenya has created a paradox that troubles agricultural economists: while supermarket shelves groan under the weight of over 40 different maize flour brands, Kenya’s own maize farmers struggle with low prices, limited markets, and chronic unprofitability.

This disconnect suggests that much of the maize flour consumed by Kenyans may not actually originate from Kenyan farms, but rather from imported cornstarch or maize from neighboring countries where production costs are lower and regulatory oversight may be lax.

Moses Ndungu, chairman of the Kenya Maize Farmers Association, expressed frustration at the situation. “Our farmers produce high-quality maize but cannot compete with cheap imports and industrial cornstarch. Meanwhile, millers make huge profits by adding chemicals to make their products look and feel premium. Who really benefits from this system? Certainly not Kenyan farmers or consumers.”

While aflatoxin contamination represents an inadvertent threat from poor storage and handling, the deliberate addition of chemical improvers and bleaching agents raises ethical questions about the food industry’s priorities.

Benzoyl peroxide, commonly used to bleach flour and mentioned by Amerix, is approved by many food safety authorities in controlled amounts.

However, critics note that it’s the same chemical used in acne treatments and industrial applications, and question why it needs to be in staple foods consumed daily by entire populations, including vulnerable children and pregnant women.

Chlorine dioxide, another bleaching agent, is permitted as a flour treatment agent but has faced scrutiny over potential formation of chlorinated byproducts. The European Union banned its use in food production over a decade ago, yet it remains permissible in many other jurisdictions including Kenya.

The phrase “over five improvers” used by the New Paleah Millers representative is particularly troubling because it suggests a complex cocktail of additives whose combined effects may never have been adequately studied.

While individual chemicals may be deemed “safe” in isolation, the interaction effects of multiple additives consumed together, repeatedly, over years, remain poorly understood.

Dr. Lucy Mwangi, a biochemist specializing in food additives, cautioned that regulatory frameworks have not kept pace with modern food processing practices.

“We approve additives one by one based on toxicity studies, but we don’t adequately assess what happens when consumers are exposed to combinations of five, ten, or fifteen different chemicals in a single food product consumed three times daily for their entire lives.”

In response to growing public concern, some experts advocate for a return to traditional food preparation methods that minimize industrial processing.

Stone-ground maize flour, produced by local posho mills without chemical additives, offers an alternative for consumers willing to sacrifice convenience for authenticity.

However, these traditional options come with their own risks.

Unregulated small-scale mills lack the testing equipment to screen for aflatoxins, potentially exposing consumers to even greater danger than commercial products.

Without proper moisture control and storage, home-milled or locally-milled maize can harbor deadly fungal toxins.

The dilemma facing Kenyan consumers is stark: trust industrial processors who admit to extensive chemical manipulation, or return to traditional methods that may harbor invisible biological hazards.

One promising solution receiving renewed attention is Aflasafe, a biocontrol technology developed specifically for African conditions.

Aflasafe consists of harmless strains of Aspergillus fungi that outcompete the toxin-producing varieties, reducing aflatoxin contamination in maize fields by 80-100% before harvest.

Approved for use in Kenya and adopted across multiple African countries, Aflasafe addresses the problem at its source rather than relying on downstream testing and rejection of contaminated grain.

However, adoption rates among Kenyan smallholder farmers remain disappointingly low, hampered by limited awareness, distribution challenges, and upfront costs that many farmers cannot afford.

Agricultural extension officers report that many farmers remain unaware that the fungi causing aflatoxin contamination can be prevented through pre-harvest biocontrol, instead focusing solely on post-harvest drying and storage.

In the wake of the New Paleah Millers admission, consumer advocacy groups are demanding greater transparency from all maize flour producers.

Calls are mounting for mandatory disclosure of all chemical additives on product labels, not buried in fine print but prominently displayed so consumers can make informed choices.

“We have a right to know exactly what chemicals are in our food and why they’re there,” said Grace Akinyi, founder of the Kenyan Food Consumers Network. “If a company is adding five or more improvers to make ugali balloon, we need to know what those improvers are, whether they’re necessary for nutrition or just for profit, and what the long-term health effects might be.”

The Kenya Bureau of Standards, which oversees food safety regulations, has remained conspicuously silent since the NTV interview aired. Multiple attempts by The Star to reach KEBS officials for comment were unsuccessful, with calls and messages going unanswered.

This silence has only intensified public speculation about potential regulatory capture or industry influence over food safety oversight.

As the controversy intensifies online, with Amerix’s posts generating thousands of shares and comments, a broader conversation is emerging about Kenya’s food system and the erosion of traditional foodways in favor of industrialized, chemically-enhanced products marketed as “improvements.”

Many Kenyans are now questioning whether the march toward modern food processing has actually improved their nutrition and health, or merely enriched processors while exposing consumers to novel risks that previous generations never faced.

The stark images shared by Amerix showing supermarket aisles dominated by dozens of identical-looking bags of ultra-white maize flour have become a symbol of this anxiety. Each pristine package represents not traditional food but an industrial product engineered for appearance, shelf-stability, and profitability rather than optimal nutrition.

For now, health experts recommend that consumers concerned about chemical additives and aflatoxin contamination take several precautions: diversify grain consumption beyond maize to include millet, sorghum, and other traditional cereals; purchase maize flour from reputable brands that provide transparent ingredient information; store flour in cool, dry conditions and use it quickly; and consider whole-grain options that undergo less processing.

Above all, consumers should demand accountability from food manufacturers and regulators. The casual admission by New Paleah Millers that they add multiple chemical improvers to make ugali “balloon” should not be normalized or accepted as standard industry practice without rigorous public scrutiny.

As one commenter on Amerix’s viral post succinctly put it: “Our grandparents ate maize flour without chemicals and lived healthy lives. Why do we suddenly need five improvers to make ugali? Who asked for this?”

It’s a question that New Paleah Millers, the broader maize flour industry, and Kenya’s food safety regulators have yet to adequately answer.

Until they do, millions of Kenyans will continue consuming their daily ugali with a new and unsettling awareness that their staple food has become a science experiment whose long-term consequences remain unknown.

(Click to watch the video)

c724fc581629c8a3ef3b1fe0cf81f725f2c880a4

Kenya Insights has reached out to New Paleah Millers for detailed comment on the specific chemical improvers used in Lea Premium Maize Flour and the health and safety testing conducted on the final product. This story will be updated if and when the company responds.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoBillions Stolen, Millions Laundered: How Minnesota’s COVID Fraud Exposed Cracks in Somali Remittance Networks

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoUS Moves to Seize Luxury Kenya Properties in Sh39 Billion Covid Fraud Scandal

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoJulius Mwale Throws Contractor Under the Bus in Court Amid Mounting Pressure From Indebted Partners

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoMAINGA CLINGS TO POWER: Kenya Railways Boss Defies Tenure Expiry Amid Corruption Storm and Court Battles

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoEastleigh Businessman Accused of Sh296 Million Theft, Money Laundering Scandal

-

Americas1 week ago

Americas1 week agoUS Govt Audits Cases Of Somali US Citizens For Potential Denaturalization

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoEXPLOSIVE: BBS Mall Owner Wants Gachagua Reprimanded After Linking Him To Money Laundering, Minnesota Fraud

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoMost Safaricom Customers Feel They’re Being Conned By Their Billing System