News

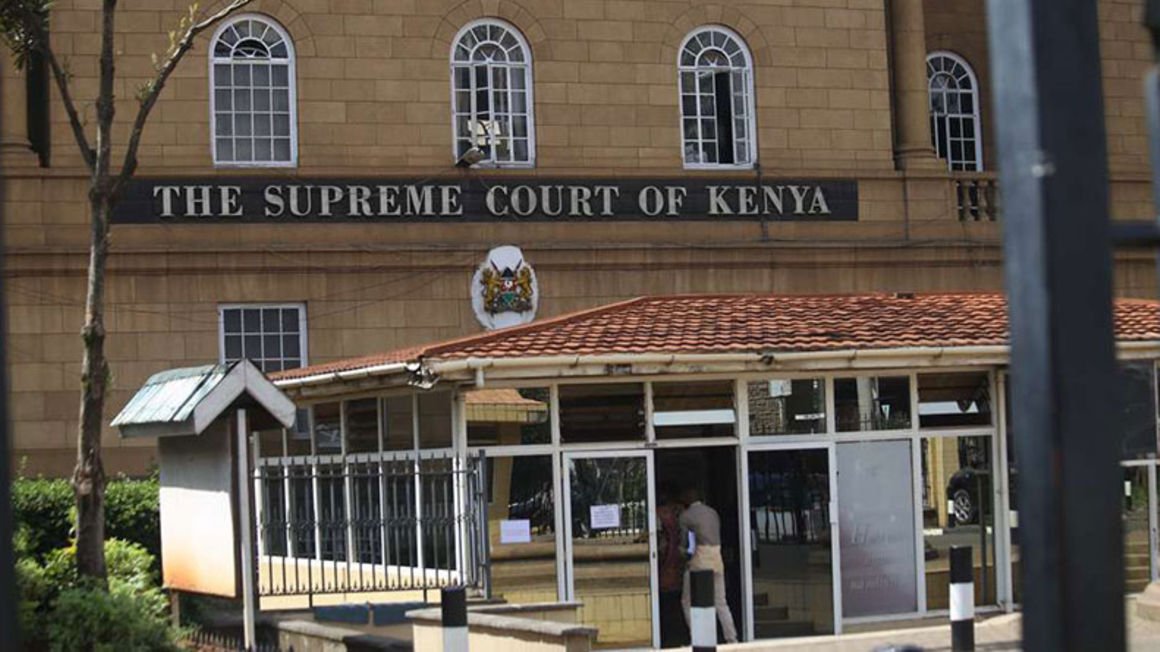

Kenya Supreme Court Recognizes Business Goodwill as Constitutional Property Right

Kenya’s Supreme Court has issued a landmark ruling establishing that business goodwill constitutes a form of property protected under the country’s Constitution, marking a significant development in commercial law that could reshape how distribution agreements and business relationships are structured.

The decision emerged from a dispute between Bavaria N.V., a beverage manufacturer, and Jovet (Kenya) Limited, which had been distributing Bavaria’s non-alcoholic beverages in Kenya through an informal arrangement with the manufacturer’s official Tanzanian distributor from 2006 to 2015.

When Bavaria declined to renew its distribution agreement covering the Kenyan market in 2015, Jovet Kenya filed suit claiming it had developed substantial goodwill for Bavaria’s products through investments in warehouses, branded outlets, delivery trucks, marketing campaigns, and sales staff.

The company argued these efforts gave it exclusive rights to continue distributing Bavaria’s products in Kenya.

However, the Supreme Court upheld lower court rulings that dismissed Jovet Kenya’s claims, finding no direct contractual relationship existed between the company and Bavaria.

Crucially, the court established that a sub-distributor cannot claim goodwill through a parent distributor without explicit provisions in the principal agreement.

Despite ruling against Jovet Kenya, the Supreme Court took the significant step of clarifying goodwill’s legal status.

The court determined that goodwill qualifies as constitutionally protected property when it is clearly identifiable and can be assigned a measurable value, either independently or alongside other business assets.

This ruling transforms goodwill from a purely commercial concept into a constitutional property right under Article 40 of Kenya’s Constitution.

Legal experts from Bowmans Kenya law firm, who analyzed the decision, note this elevation means interference with business goodwill could now be challenged as constitutional violations rather than merely commercial disputes.

The decision carries broad implications for businesses operating in Kenya.

Companies must now recognize that goodwill claims have constitutional dimensions, potentially making such disputes more complex and consequential.

The ruling also underscores the critical importance of formalizing business relationships through clear written agreements, as the absence of direct contractual links can undermine goodwill claims.

For distribution agreements specifically, the court’s emphasis on privity of contract means businesses should explicitly define the rights and obligations of all parties, including any sub-distributors or agents, and clearly outline provisions related to goodwill ownership and transferability.

The Supreme Court’s decision builds on last year’s Court of Appeal ruling in Heineken East Africa Import Company Limited v. Maxam Limited, which first suggested that distributor investments could create protected goodwill rights.

Together, these cases signal Kenya’s courts are increasingly willing to protect business investments and relationships, even in the absence of formal contractual arrangements.

This development positions Kenya at the forefront of recognizing intangible business assets as constitutional property rights, potentially influencing commercial law development across East Africa and beyond.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoTemporary Reprieve As Mohamed Jaffer Wins Mombasa Land Compensation Despite Losing LPG Monopoly and Bitter Fallout With Johos

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoPanic As Payless Africa Freezes With Billions of Customers Cash After Costly Jambopay Blunder

-

Investigations4 days ago

Investigations4 days agoFrom Daily Bribes to Billions Frozen: The Jambopay Empire Crumbles as CEO Danson Muchemi’s Scandal-Plagued Past Catches Up

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoHow SportPesa Outfoxed Paul Ndung’u Of His Stakes With A Wrong Address Letter

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days ago1Win Games 2025: Ultimate Overview of Popular Casino, Sports & Live Games

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoSCANDAL: Cocoa Luxury Resort Manager Returns to Post After Alleged Sh28 Million Bribe Clears Sexual Harassment and Racism Claims

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoHass Petroleum Empire Faces Collapse as Court Greenlights KSh 1.2 Billion Property Auction

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoInside the Deadly CBD Chase That Left Two Suspects Down After Targeting Equity Bank Customer Amid Insider Leak Fears