News

Morara Refunds Cash to Clear Himself From ‘Conman’ Tag

During a recent interview on Andrew Kibe’s platform, Morara revealed he had returned the donated mansion after quitting active politics, explaining that it had been gifted by a Kikuyu couple who believed in his political mission.

Civic educator and politician Morara Kebaso has initiated a three-day refund process for citizens who contributed to his political activities, citing concerns about being labeled a conman and the psychological toll of public accusations.

In an emotional statement posted on his social media platforms, Kebaso announced that anyone who feels “robbed or conned” by contributing to his civic education efforts can request a full refund by providing their M-Pesa transaction details.

“I have been traumatized everyday to look like a thief. Am not ready to carry that burden into my future,” Kebaso declared, emphasizing that his reputation holds more value than money

The INJECT party leader has given contributors a 72-hour window to submit their M-Pesa reference codes or transaction messages for verification and subsequent refunds.

Kebaso’s rise to political prominence began in 2024 during Kenya’s youth-led protests, where his “Vampire Diaries” exposés of government projects earned him widespread support.

His mobile account, with a limit of KSh 500,000, received endless contributions from Kenyans who believed in his anti-corruption mission.

The overwhelming public support extended beyond monetary donations.

A family friend living abroad donated a luxurious house in Kahawa Sukari, Nairobi County, to serve as his office headquarters and operational base.

The gesture symbolized the faith many Kenyans had placed in his political activism.

However, the fairy tale took a dramatic turn.

During a recent interview on Andrew Kibe’s platform, Morara revealed he had returned the donated mansion after quitting active politics, explaining that it had been gifted by a Kikuyu couple who believed in his political mission.

The decision to offer refunds stems from what Kebaso describes as daily trauma from accusations of financial impropriety.

His statement reveals the psychological burden of public scrutiny, particularly from those who question his handling of donated funds.

“If you need a refund for any contribution you made to me when I was raising funds, kindly reply below with the Mpesa message,” Kebaso wrote, addressing contributors who may have interpreted his efforts as politically motivated rather than civic education.

The refund initiative appears to be both a defensive move and an attempt to clear his name definitively.

“I cannot continue to dirty my reputation and earn the tag of a conman or beggar. It’s not worth it,” he stated, indicating his willingness to sacrifice financial resources to protect his public image.

Already processing returns

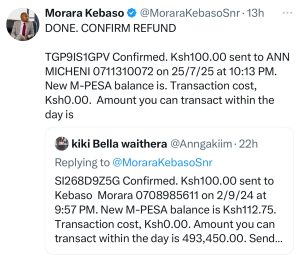

Kebaso has already begun processing refunds, with reports showing he has returned money to individual contributors.

Recent evidence shows he returned KSh 500 to a woman who had donated toward his campaign and political work, demonstrating his commitment to the refund promise.

The process involves careful verification of transactions to ensure legitimacy.

Contributors are required to submit either their original M-Pesa messages or reference codes obtained from their mobile money statements.

Kebaso’s team has indicated they will verify each transaction before processing refunds.

This refund initiative comes at a time when Kebaso has stepped back from active politics, having announced his exit from the political arena earlier this year.

The move raises questions about the sustainability of grassroots political movements that rely heavily on public contributions.

The refund is primarily intended for individuals who feel their support was misunderstood as political endorsement, suggesting Kebaso seeks to distinguish between civic education and political campaigning in the public mind.

His decision to prioritize reputation over financial resources reflects the complex relationship between public figures and their supporters in Kenya’s digital age, where social media can quickly transform heroes into villains.

Kebaso’s situation highlights the challenges facing grassroots political movements in Kenya. The ease with which public contributions can be mobilized through mobile money platforms has democratized political fundraising, but it has also created new vulnerabilities for recipients.

The civic educator’s experience demonstrates how quickly public sentiment can shift, particularly when financial transparency becomes a contentious issue. His proactive approach to addressing these concerns through voluntary refunds represents an unusual response in Kenyan politics, where such accountability measures are rarely seen.

As the three-day refund window progresses, Kebaso’s initiative will likely serve as a precedent for how political figures handle public contributions amid controversy.

Whether this move will restore his reputation or mark the end of his political influence remains to be seen.

The story of Morara Kebaso serves as a cautionary tale about the double-edged nature of public support in Kenya’s evolving political landscape, where social media fame and crowdfunded activism can quickly transform from assets into liabilities.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoKenyan Driver Hospitalized After Dubai Assault for Rejecting Gay Advances, Passport Seized as Authorities Remain Silent

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoKakuzi Investors Face Massive Loss as Land Commission Drops Bombshell Order to Surrender Quarter of Productive Estate

-

Investigations2 weeks ago

Investigations2 weeks agoINSIDER LEAK REVEALS ROT AT KWS TOP EXECUTIVES

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoConstruction Of Stalled Yaya Center Block Resumes After More Than 3 Decades and The Concrete Story Behind It

-

Investigations1 week ago

Investigations1 week agoCNN Reveals Massive Killings, Secret Graves In Tanzania and Coverup By the Govt

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoBANKS BETRAYAL: How Equity Bank Allegedly Helped Thieves Loot Sh10 Million From Family’s Savings in Lightning Fast Court Scam

-

Investigations5 days ago

Investigations5 days agoHow Somali Money From Minnesota Fraud Ended In Funding Nairobi Real Estate Boom, Al Shabaab Attracting Trump’s Wrath

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoEXPOSED: How Tycoon Munga, State Officials, Chinese Firm Stalled A Sh3.9 Trillion Coal Treasure In Kitui